United States Securities and Exchange Commission

Washington, D.C. 20549

NOTICE OF EXEMPT SOLICITATION

Pursuant to Rule 14a-103

United States Securities and Exchange Commission

Washington, D.C. 20549

NOTICE OF EXEMPT SOLICITATION

Pursuant to Rule 14a-103

Name of the Registrant: Kroger Co.

Name of persons relying on exemption: The Shareholder Commons, Inc.

Address of persons relying on exemption: PO Box 1268, Northampton, Massachusetts 01061

Written materials are submitted pursuant to Rule 14a-6(g) (1) promulgated under the Securities Exchange Act of 1934. Submission is not required of this filer under the terms of the Rule, as the filer does not own any securities of the registrant, but is made voluntarily.

Balancing Diversified Shareholder Value and Company Financial Returns

At Kroger, the average hourly wage is not enough to sustain a single adult with no children, even in low-cost areas of the United States. This failure to provide a living wage to people who work for a living threatens the entire economy, and thus the investment portfolios of the average diversified investor.

The Shareholder Commons urges (“TSC”) you to vote “AGAINST” Ronald L. Sargent, Chair of the Board (Item 1g on the proxy), due to Kroger’s failure to pay a living wage, which exposes its diversified shareholders’ portfolios to broader economic harm stemming from low wages and income inequality.

TSC is a non-profit advocate for diversified shareholders that works with investors to stop portfolio companies such as Kroger from externalizing costs in ways that can threaten the value of diversified portfolios. TSC addresses the interests of diversified shareholders in optimizing overall market returns.

Closing the global living wage gap could generate an additional $4.56 trillion in annual economic output through increased productivity and spending.1 This equates to more than a 4% increase in annual global GDP. Inadequate pay, by contrast, imposes a drag on the overall economy’s intrinsic value, which in turn harms investment portfolios reliant on broad economic growth. Kroger has failed to pay a living wage, contrary to its own diversified shareholders’ interests. A vote AGAINST Chair Ronald L. Sargent is thus warranted.

Investors have been asking Kroger for many years to improve its pay practices. TSC filed a shareholder proposal at Kroger last year asking the Company to pay a living wage, with the aim of protecting diversified portfolios from negative effects on the economy caused by inadequate wages and expanding income inequality. Kroger has so far declined to do so. Other shareholders have filed multiple similar proposals through the years seeking improved pay for Kroger’s lowest paid workers. Kroger is the largest supermarket chain in the United States2 and the sixth largest employer among U.S. public companies;3 its policies thus have tremendous influence on the market as a whole.

Given Kroger’s history of failure to address its contribution to economic damage arising from an underpaid labor force, a vote AGAINST its board chair is in investors’ best interest.

| A. | Underpaying Workers Threatens Economic Prosperity and Diversified Portfolios |

Low wages and income inequality threaten the global economy with losses that will burden investment portfolios over the next 30 years and beyond, as we explain further in Section C. Conversely, higher wages lead to increased productivity and consumption in a virtuous macroeconomic cycle that benefits investment portfolios.

Diversified investors—including pension funds, foundations, and endowments—and other institutions working on behalf of these investors and other beneficiaries with diversified portfolios must work to bring an end to employment practices at Kroger that threaten the economy upon which their portfolios depend.

In the following sections, we describe the research establishing the relationship between low wages and income inequality on the one hand and long-term returns of diversified portfolios on the other, and show why shareholders can and must steward Kroger away from pay practices that threaten the economy. This system-wide perspective is necessary to protect shareholders, whose diversified portfolios are threatened by company decisions that do not account for systemic effects.

Addressing these systemic concerns means moving beyond the measurement of investment success solely at the company level, and recognizing that portfolio returns are based not only on the profits that companies deliver, but also on the economic impact they create.

_____________________________

1 The Business Commission to Tackle Inequality, “Tackling Inequality: The Need and Opportunity for Business Action,” June 2022, https://tacklinginequality.org/files/introduction.pdf.

2 T. Ozbun, “Largest Grocery Chains in the U.S. 2022,” Statista, February 7, 2024, https://www.statista.com/statistics/197899/2010-sales-of-supermarket-chains-in-the-us/.

3 Gary Hoover, “America’s Largest Employers 1994-2022,” Business History - The American Business History Center, August 17, 2023, https://americanbusinesshistory.org/americas-largest-employers-1994-2022/.

| 2 |

| B. | Kroger’s wages are insufficient to mitigate economic damage and do not account for portfolio impact |

Kroger’s wage policies are not sufficient to mitigate the risk its diversified shareholders face to their portfolios from the economic damage that arises from an impoverished workforce and expanding income inequality.

The living wage model reflects “the minimum employment earnings necessary to meet a family’s basic needs while also maintaining self-sufficiency.”4 The living wage is abstemious, making no allowances for savings, consumption of even modest prepared foods, or home purchases, among other things. As the MIT Living Wage Calculator explains:

The living wage is the minimum income standard that, if met, draws a very fine line between the financial independence of the working poor and the need to seek out public assistance or suffer consistent and severe housing and food insecurity. In light of this fact, the living wage is perhaps better defined as a minimum subsistence wage for persons living in the United States.5

Meanwhile, the minimum wage is the lowest legal pay rate companies can offer their employees. Many people believe this is the same as a living wage, but that is not the case. Indeed, in some regions, the chasm between the two is substantial. The U.S. federal minimum wage stood at $7.25 per hour in 2024, whereas the current average living wage in the United States is around $23 per hour for a family of four with both adults working.6 While some states have higher minimums, the highest—Washington, DC’s $17 per hour—still falls well short of a living wage.

| 1. | Kroger’s cost externalization resulting from its failure to pay a living wage |

In its proxy statement, Kroger asserts that its average hourly wage is above $19. With an average hourly wage that falls well short of a living wage, Kroger clearly underpays many of its workers, especially those at starting wages in the lowest-paid jobs.

Kroger does not disclose its lowest pay rates, forcing its shareholders to rely on outside sources for this information. For instance, jobs site ZipRecruiter reports hourly wages for Kroger clerks in Alabama as low as $7.32, with the majority of Kroger clerk hourly wages ranging between $10.98 (25th percentile) to $14.43 (75th percentile) in that state.7 None of those comes close to Alabama’s living wage. The table below more fully illustrates the substantial gap between Kroger’s wages and living wages in a variety of markets.

_____________________________

4 https://livingwage.mit.edu/pages/about (Living wage is a “market-based approach that draws upon geographically specific expenditure data related to a family’s likely minimum food, childcare, health insurance, housing, transportation, and other basic necessities (e.g. clothing, personal care items, etc.) costs. The living wage draws on these cost elements and the rough effects of income and payroll taxes to determine the minimum employment earnings necessary to meet a family’s basic needs while also maintaining self-sufficiency.”)

5 Ibid.

6 Emma Burleigh, “Americans Are Struggling to Scrape by—More than 40% of Full-Time Workers Aren’t Making a Living Wage,” Fortune, August 26, 2024, https://fortune.com/2024/08/26/many-us-workers-dont-make-living-wage-women-people-of-color/.

7 https://www.ziprecruiter.com/Salaries/Kroger-Clerk-Salary--in-Alabama

| 3 |

Kroger-owned stores are located in areas with varying costs of living. Noting that, we provide in the following table the current living wage for a range of Kroger-owned store locations, along with the wage Kroger reportedly pays in those locations:8

| Kroger Wage vs. Living Wage (hourly) | ||||

| Store Location | Lowest Kroger Wage in State |

25th Percentile Kroger Wage |

Living Wage: 1 adult, 0 children |

Living Wage: 2 working adults, 2 children |

| Middlesboro, KY | $8.08 | $12.11 | $17.54 | $19.59 |

| Hartselle, AL | $7.32 | $10.98 | $19.98 | $22.95 |

| Columbia, SC | $7.99 | $11.98 | $21.54 | $24.90 |

| Columbus, OH | $7.91 | $11.87 | $22.42 | $28.18 |

| Atlanta, GA | $7.25 | $10.96 | $26.28 | $27.44 |

Sources: Kroger wage rates from ZipRecruiter and Indeed.com, Living Wage Rates from MIT Living Wage Calculator

In other words, Kroger’s lowest pay is deeply inadequate no matter the employee’s location or family situation, and its average wage fails to meet the basic needs of single, childless employees even in the most economically disadvantaged areas of the country. The average Kroger worker makes far less than necessary to sustain a family of four with both adults working full time, even in locations with the lowest cost of living. Kroger’s average hourly wage isn’t even enough to sustain a single adult with no children in the lowest cost-of-living location cited above.

Kroger employees have also accused the Company of lying about the wage rates it pays. In late 2022, 10TV—a Central Ohio news station—spoke with Kroger workers about their pay, and heard multiple allegations that the workers’ wages did not comport with the Company’s public statements about its pay rates. “I promise you that starting pay that they posted is an out-and-out lie. I have been with Kroger for over 23 years. I’m just at $18 an hour,” said one Kroger worker in an email to the station. Another employee provided pay stubs to prove he was making just $15 hourly, despite a September 19, 2022 Kroger press release saying “a cashier’s current wage is $17.10 an hour.” Kroger subsequently told 10TV that the $17.10 figure in the Company’s press release was the average salary for a full-time cashier, not the starting wage or what every cashier was making at the time.9

The Economic Roundtable, a nonprofit research group that surveyed more than 10,000 Kroger workers in Washington, Colorado, and Southern California about their working conditions for a 2022 report commissioned by four units of the United Food and Commercial Workers Union, found that about 75 percent of Kroger workers said they were food insecure, meaning they lacked consistent access to enough food for an active, healthy life. About 14 percent said they were homeless or had been homeless in the previous year, and 63 percent said they did not earn enough money to pay for basic expenses every month.10

_____________________________

8 See MIT’s Living Wage Calculator at https://livingwage.mit.edu/

9 Kevin Landers, “Kroger Defends Salary Figures While Employees Say They Are ‘an out-and-out Lie,’” 10tv.com, September 19, 2022, https://www.10tv.com/article/news/local/kroger-defends-salary-figures-while-employees-say-they-are-an-out-out-lie/530-7f391bc6-eb00-4c02-a1e6-1edd8282b980.

10 Daniel Flaming et al., “Hungry at the Table: White Paper on Grocery Workers at the Kroger Company” (Economic Roundtable, January 11, 2022), https://economicrt.org/publication/hungry-at-the-table/.

| 4 |

Kroger was the sole employer for 86 percent of those surveyed, partly because more than half had schedules that changed at least every week, making it difficult to commit to another employer. About two-thirds said they were part-time workers, even though they wanted more hours.11 A 2022 New York Times article describes how keeping workers part time is a strategy employers use to encourage turnover and reduce costs.12

In a May 2025 update to its report,13 the Economic Roundtable found that understaffing at Kroger exacerbates the industry-wide issue of depressed wages, and hours denial without a meaningful increase in hourly pay makes it even more difficult for grocery workers to earn a living wage. The report estimates that Kroger decreased labor hours despite increased demand due to e-commerce sales, leading to a labor shortfall of 21 percent relative to 2019. Many of the surveyed workers reported struggling to afford monthly expenses such as rent, with more than two-thirds of grocery workers saying they did not have secure housing. Just 16 percent said they made enough money to cover basic expenses.

In its Opposition Statement to our proposal last year, Kroger pointed to its benefits package, saying its “average hourly rate inclusive of benefits like [sic] health care and retirement is nearly $25 per hour.” This statement demonstrated Kroger’s unfamiliarity with what constitutes a living wage. The MIT living wage calculations cited above already assume employer-provided health insurance, for instance, and the wage calculation for each location is what is necessary for a person to meet their basic needs after factoring in the value of standard benefits. Additionally, when companies calculate their wages inclusive of benefits, they almost always do so by evaluating what the benefit cost the company, rather than the value the benefit conferred on the employee. These can be radically different.14 This is why we pointed in our Proposal to external expert frameworks such as the one developed by Living Wage for US.15 Such frameworks can help companies to assess the true value of their compensation packages to employees.

Corresponding to Kroger’s current failure to pay many of its employees a living wage, there is also significant wage inequality within the Company. According to the Company’s 2025 Proxy Statement, the Company’s CEO made $15.6 million in the previous fiscal year, or 457 times more than the Company’s median employee.

In its Opposition Statement to our proposal last year, Kroger asserted, “there are no meaningful differences in pay on an adjusted basis for associates who self-identify as male, female or a person of color.” We do not dispute that assertion, but it is not responsive to Kroger’s contribution to expanding, economy-wide racial disparity in income: women and people of color make up a disproportionate number of employees not earning a living wage because Kroger’s workforce is 49.2 percent female and 43.3 percent people of color, yet these groups compose only 33.2 percent and 28.4 percent of store leaders.16

_____________________________

11 Flaming et al., “Hungry at the Table.”

12 Noam Scheiber, “Despite Labor Shortages, Workers See Few Gains in Economic Security,” The New York Times, February 1, 2022, sec. Business, https://www.nytimes.com/2022/02/01/business/economy/part-time-work.html.

13 Daniel Flaming and Patrick Burns, “Bullies At The Table: Consequences of Understaffing by Kroger and Albertson’s” (Economic Roundtable, May 7, 2025), https://economicrt.org/publication/bullies-at-the-table/.

14 Telephone conversation with Michelle Murray, CEO of Living Wage for US, on May 15, 2024.

15 https://livingwageforus.org/becoming-certified/

16 https://www.thekrogerco.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/Kroger-Co-2024-ESG-Report.pdf

| 5 |

It appears Kroger’s decision not to pay a living wage is attributable to a Company approach to compensation that does not account for economy- or portfolio-wide risk mitigation, and instead focuses on risks to its own business.

| 2. | The broad economic cost associated with poverty wages and income inequality surpasses any risk the issue poses to Kroger itself |

It has been estimated that a one percent increase in inequality leads to a decrease in GDP of 0.6-1.0 percent.17 A one percent difference in inequality could thus lead to 17-26 percent lower GDP over 30 years and correspondingly lower returns for a diversified portfolio. This means that a 32-year-old worker saving for retirement today through a defined contribution plan could expect to have a nest egg 17-26 percent smaller at age 62. A defined benefit plan facing the same deficit could be forced to lower its benefits significantly, increase employer or employee contributions, or—in the case of a public pension fund—increased tax burdens.

We cover more empirical evidence of the economic damage associated with an underpaid labor force in the next section.

| C. | Poverty wages and income inequality threaten the returns of Kroger’s diversified investors |

| 1. | Investors must diversify to optimize their portfolios |

It is commonly understood that investors are best served by diversifying their portfolios.18 Diversification allows investors to reap the increased returns available from risky securities while greatly reducing that risk.19 This core principle is reflected in federal law, which requires fiduciaries of federally regulated retirement plans to “diversify[] the investments of the plan.”20 Similar principles govern other investment fiduciaries.21

| 2. | The performance of a diversified portfolio largely depends on overall market return |

Diversification is thus required by accepted investment theory and imposed by law on investment fiduciaries. Once a portfolio is diversified, the most important factor determining return will not be how the companies in that portfolio perform relative to other companies (“alpha”), but rather how the market performs as a whole (“beta”). In other words, the financial return to such diversified investors chiefly depends on the performance of the market, not the performance of individual companies. As one work describes this, “virtually all investors have permanent exposure to systematic market risk, which will still determine 75-95% of their return.”22

_____________________________

17 Orsetta Causa, Alain de Serres, and Nicolas Ruiz, “Growth and Inequality: A Close Relationship?,” OECD, 2014, https://www.oecd.org/content/dam/oecd/en/publications/reports/2014/06/oecd-yearbook-2014_g1g45233/observer-v2013-5-en.pdf, p. 28.

18 See generally, Burton Gordon Malkiel, A Random Walk down Wall Street: The Time-Tested Strategy for Successful Investing (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2020).

19 Malkiel, A Random Walk down Wall Street.

20 29 USC Section 404(a)(1)(C).

21 See Uniform Prudent Investor Act, § 3 (“[a] trustee shall diversify the investments of the trust unless the trustee reasonably determines that, because of special circumstances, the purposes of the trust are better served without diversifying.”)

22 Stephen Davis, Jon Lukomnik, and David Pitt-Watson, What They Do with Your Money How the Financial System Fails Us and How to Fix It (Yale University Press, 2016).

| 6 |

As shown in the next section, the social and environmental impacts of individual companies such as Kroger can significantly affect beta.

| 3. | Costs companies impose on social and environmental systems heavily influence beta |

Over long time periods, beta is influenced chiefly by the performance of the economy itself, because the value of the investable universe is equal to the portion of the productive economy that the companies in the market represent.23 Over the long run, diversified portfolios rise and fall with GDP or other indicators of the intrinsic value of the economy. As the legendary investor Warren Buffet puts it, GDP is the “best single measure” for broad market valuations.24

But the social and environmental costs created by companies pursuing profits can burden the economy.25 For example, recent research revealed rising income inequality’s drag on GDP. The increase in income inequality between 1979 and 2018 reduced growth in aggregate demand by about 1.5 percent of GDP. Relative to the 1979 baseline, rising income inequality lowered aggregate demand growth by more than 4 percent annually in the United States.26

Additional research reveals that income inequality and attendant racial and gender disparity harm the entire economy. According to the Economic Policy Institute, income inequality is slowing U.S. economic growth by reducing demand by 2-4 percent.27 The Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco determined that gender and racial gaps created $2.9 trillion in losses to U.S. GDP in 2019.28 Moreover, a recent report from Citigroup found that had four key racial gaps for Black Americans—wages, education, housing, and investment—been closed in 2000, $16 trillion could have been added to the U.S. economy. Closing those gaps in 2020 could have added $5 trillion to the U.S. economy over the ensuing five years.29 The same study explains steps that corporations could take to reduce the gap. This drag on GDP directly reduces the return on a diversified portfolio over the long term.

Conversely, closing the living wage gap worldwide could generate an additional $4.56 trillion every year through increased productivity and spending,30 which equates to a more than 4 percent increase in annual GDP.

_____________________________

23 Richard Mattison, Mark Trevitt, and Liesl van Ast, “Universal Ownership: Why Environmental Externalities Matter to Institutional Investors” (UNEP Finance Initiative and PRI, October 6, 2010), https://www.unepfi.org/fileadmin/documents/universal_ownership_full.pdf, Appendix IV.

24 Warren Buffett and Carol Loomis, “Warren Buffett on the Stock Market,” Fortune Magazine (December 10, 2001), available at https://archive.fortune.com/magazines/fortune/fortune_archive/2001/12/10/314691/index.htm.

25 The Shareholder Commons, “Living Wage & the Engagement Gap: Using a Systems Lens to Build Portfolio Value through Improved Wages,” November, 2023, https://theshareholdercommons.com/case-studies/labor-and-inequality-case-study/.

26 Josh Bivens and Asha Banerjee, “Inequality’s Drag on Aggregate Demand - The Macroeconomic and Fiscal Effects of Rising Income Shares of the Rich” (Economic Policy Institute, 2022), https://www.epi.org/publication/inequalitys-drag-on-aggregate-demand/#:~:text=By%20redistributing%20income%20from%20lower,about%201.5%25%20of%20GDP%20annually.

27 Josh Bivens, “Inequality Is Slowing U.S. Economic Growth: Faster Wage Growth for Low- and Middle-Wage Workers Is the Solution” (Economic Policy Institute, December 12, 2017), https://www.epi.org/publication/secular-stagnation/.

28 Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco et al., “The Economic Gains from Equity,” Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco, Working Paper Series, April 7, 2021, 1.000-30.000, https://doi.org/10.24148/wp2021-11.

29 Dana Peterson and Catherine Mann, “Closing the Racial Inequality Gaps: The Economic Cost of Black Inequality in the U.S.” (Citi, September 2020), https://ir.citi.com/%2FPRxPvgNWu319AU1ajGf%2BsKbjJjBJSaTOSdw2DF4xynPwFB8a2jV1FaA3Idy7vY59bOtN2lxVQM=.

30 The Business Commission to Tackle Inequality, “Tackling Inequality: The Need and Opportunity for Business Action,” June 2022, https://tacklinginequality.org/files/introduction.pdf.

| 7 |

The reduction in economic productivity caused by income inequality and racial disparity directly reduces returns on diversified portfolios,31 and creates serious social costs that further threaten financial markets. For example, excessive inequality can erode social cohesion and heighten political polarization, leading to social instability.32

Excessive inequality is also a social determinant of health that is linked to more chronic health conditions developed earlier in life, thereby increasing health costs and decreasing the value of human capital.33 A recent study found that “a sustained history of low-wage earning in midlife was associated with significantly earlier and excess mortality, especially for workers whose low-wage earning was experienced in the context of employment instability.”34 Early and excess mortality, in turn, has its own economic costs. Researchers calculated a potential economic output loss of up to 2.6 percent of GDP by 2030 in low-income countries and 0.9 percent in upper-middle-income countries from early and excess mortality.35

A U.S. Government Accountability Office report36 revealed how taxpayers foot the bill when corporations underpay their workers. Millions of full-time workers rely on federal health care and food assistance programs just to get by, and the wholesale and retail trade is in the top five industries with the highest concentration of working adults enrolled in Medicaid and SNAP.37 This, of course, is a form of corporate welfare, in that taxpayers—and, by extension, shareholders—are subsidizing employers who pay low wages.

_____________________________

31 Ibid n.15.

32 International Monetary Fund, IMF Fiscal Monitor: Tackling Inequality (October 2017), available at https://www.imf.org/en/publications/fm/issues/2017/10/05/fiscal-monitor-october-2017.

33 Anne Matusewicz and Henry Mason, “Facing Hard Truths: The Material Risk of Rising Inequality,” Pensions & Investments, September 16, 2020, https://www.pionline.com/sponsored-content/facing-hard-truths-material-risk-rising-inequality.

34 Katrina L. Kezios et al., “History of Low Hourly Wage and All-Cause Mortality Among Middle-Aged Workers,” JAMA 329, no. 7 (February 21, 2023): 561, https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2023.0367.

35 Blake C. Alkire et al., “The Economic Consequences Of Mortality Amenable To High-Quality Health Care In Low- And Middle-Income Countries,” Health Affairs 37, no. 6 (June 2018): 988–96, https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2017.1233.

36 United States Government Accountability Office, Federal Social Safety Net Programs: Millions of Full-Time Workers Rely on Federal Health Care and Food Assistance Programs (October 2020), available at https://www.gao.gov/assets/gao-21-45.pdf.

37 Ibid.

| 8 |

For a full survey of the empirical evidence for the economic damage arising from poverty wages and income inequality, see The Shareholder Commons, “Living Wage & the Engagement Gap: Using a Systems Lens to Build Portfolio Value through Improved Wages,” November, 2023, https://theshareholdercommons.com/case-studies/labor-and-inequality-case-study/.

The acts of individual companies affect whether the economy will bear these costs: if they increase their own bottom line by underpaying workers, the profits earned for and capital returned to their shareholders may be inconsequential in comparison to the added costs the economy bears.

Economists have long recognized that profit-seeking firms will not account for costs they impose on others, and there are many profitable strategies that harm shareholders, society, and the environment.38 Indeed, in 2018, publicly listed companies around the world imposed social and environmental costs on the economy with a value of $2.2 trillion annually—more than 2.5 percent of global GDP.39 This cost was more than 50 percent of the profits those companies reported.

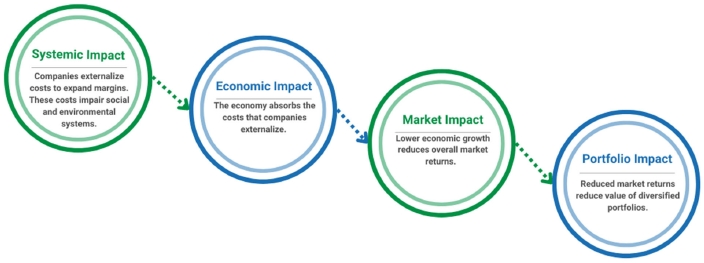

As shown in Figure 1, Kroger’s choices that contribute to a financially insecure labor force threaten its diversified shareholders’ financial returns, even if those decisions might benefit Kroger financially.

Figure 1

_____________________________

38 See, e.g., Kaushik Basu, Beyond the Invisible Hand: Groundwork for a New Economics, (Princeton University Press, 2011), p.10 (explaining the First Fundamental Theorem of Welfare Economics as the strict conditions (including the absence of externalities) under which competition for profit produces optimal social outcomes).

39 Andrew Howard, “SustainEx: Examining the Social Value of Corporate Activities” (Schroders, April 2019), https://www.schroders.com/en-ch/ch/professional/insights/sustainex-quantifying-the-hidden-costs-of-companies-social-impacts/.

| 9 |

Kroger’s disclosures demonstrate that its compensation strategy simply fails to address the economic costs of poverty wages and income inequality.

| D. | Why you should vote “AGAINST” the Board Chair |

Voting “AGAINST” the Board Chair will signal to Kroger that shareholders want the Company not to put the economy (and thus their diversified portfolios) at risk.

Additionally:

| · | Kroger underpays its workers, which creates an economy-wide risk that poses a threat to diversified shareholders. |

| · | Kroger’s disclosures show it is not taking the actions that are required of corporations seeking to end practices that externalize costs onto the broader economy and diversified shareholders. |

| · | Kroger’s decision-makers—who are heavily compensated in equity—may not share the same broad market risk as Kroger’s diversified shareholders. |

| E. | Conclusion |

Please vote “AGAINST” Ronald L. Sargent, Item 1g.

By voting “AGAINST” Item 1g, shareholders can urge Kroger to account directly for its poverty wages and the resulting costs to society, which in turn affect the economic health upon which diversified portfolios depend. Paying a living wage can aid the Board and management in authentically serving the needs of Kroger’s diversified shareholders and in preventing the dangerous implications—to diversified shareholders and others—of a narrow focus on internal financial return.

The Shareholder Commons urges you to vote “AGAINST” Ronald L. Sargent, Board Chair (Item 1g on the proxy), over Kroger’s failure to protect its diversified shareholders’ portfolios by paying a living wage, at the Kroger Co. Annual Meeting on June 26, 2025.

For questions regarding this exempt solicitation, please contact Sara E. Murphy of The Shareholder Commons at +1.202.578.0261 or via email at sara@theshareholdercommons.com.

THE FOREGOING INFORMATION MAY BE DISSEMINATED TO SHAREHOLDERS VIA TELEPHONE, U.S. MAIL, E-MAIL, CERTAIN WEBSITES, AND CERTAIN SOCIAL MEDIA VENUES, AND SHOULD NOT BE CONSTRUED AS INVESTMENT ADVICE OR AS A SOLICITATION OF AUTHORITY TO VOTE YOUR PROXY.

PROXY CARDS WILL NOT BE ACCEPTED BY THE SHAREHOLDER

COMMONS.

TO VOTE YOUR PROXY, PLEASE FOLLOW THE INSTRUCTIONS ON YOUR PROXY CARD.

10