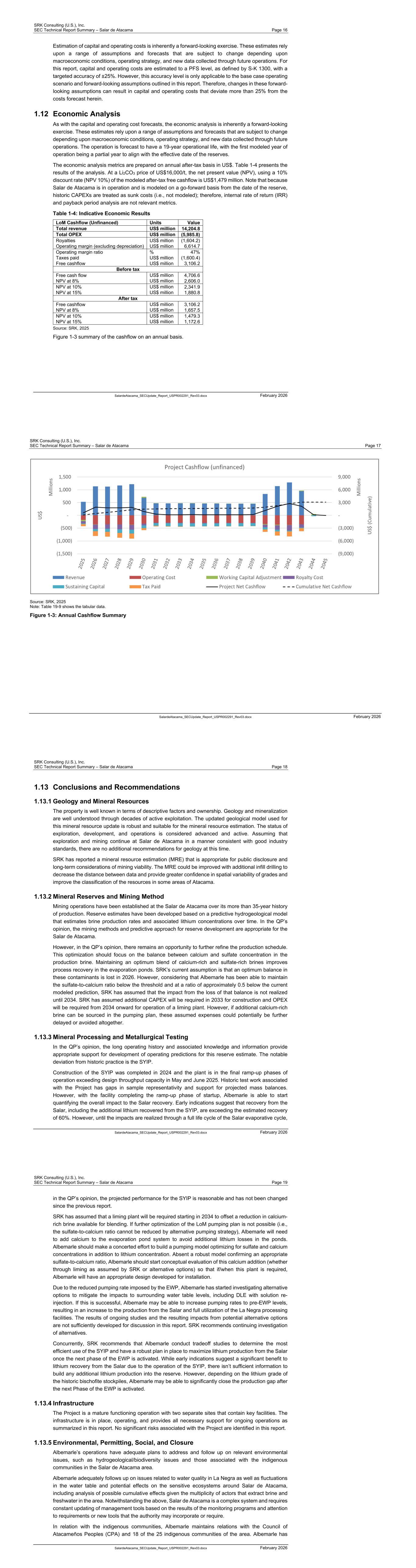

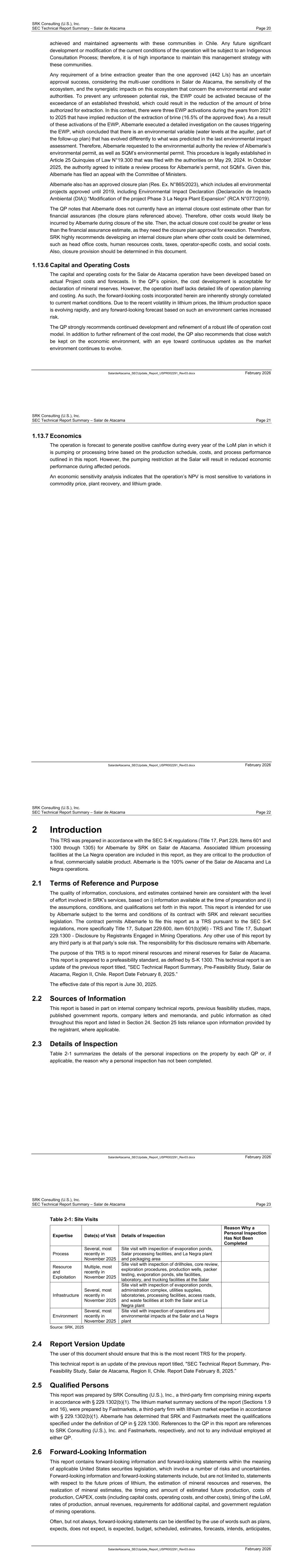

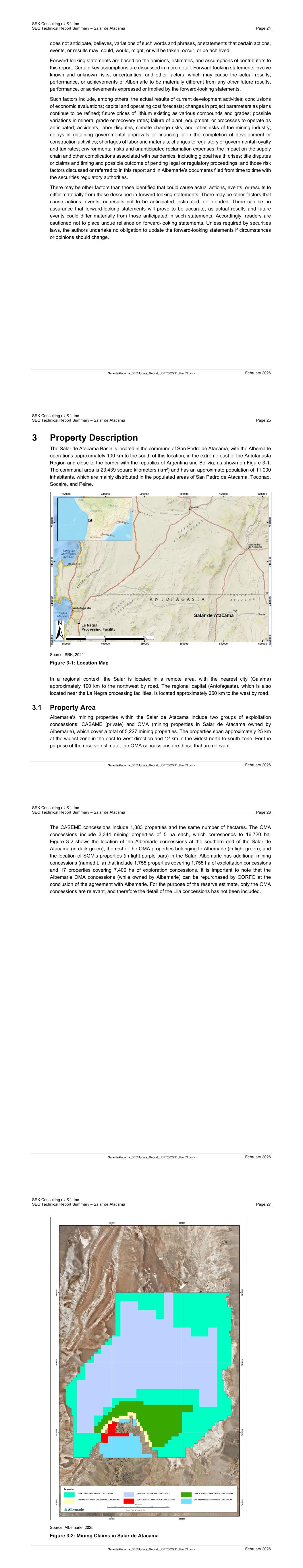

SEC Technical Report Summary Prefeasibility Study Salar de Atacama Región II, Chile Effective Date: June 30, 2025 Report Date: February 9, 2026 Report Prepared for Albemarle Corporation 4250 Congress Street Suite 900 Charlotte, North Carolina 28209 Report Prepared by SRK Consulting (U.S.), Inc. 999 Seventeenth Street, Suite 400 Denver, CO 80202 SRK Project Number: USPR002291 Exhibit 96.3 SRK Consulting (U.S.), Inc. SEC Technical Report Summary – Salar de Atacama Page i SalardeAtacama_SECUpdate_Report_USPR002291_Rev03.docx February 2026 Table of Contents 1 Executive Summary ..................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Property Description ............................................................................................................................ 1 1.2 Geology and Mineralization ................................................................................................................ 2 1.3 Status of Exploration, Development, and Operations ......................................................................... 3 1.4 Mineral Processing and Metallurgical Testing .................................................................................... 3 1.5 Mineral Resource Estimate ................................................................................................................. 3 1.6 Mining Methods and Mineral Reserve Estimates ............................................................................... 6 1.7 Processing and Recovery Methods .................................................................................................. 10 1.8 Infrastructure ..................................................................................................................................... 11 1.9 Market Studies .................................................................................................................................. 11 1.10 Environmental Studies, Permitting, and Plans, Negotiations, or Agreements with Local Individuals or Groups .............................................................................................................................................. 12 1.11 Capital and Operating Costs ............................................................................................................. 14 1.12 Economic Analysis ............................................................................................................................ 16 1.13 Conclusions and Recommendations ................................................................................................ 18 1.13.1 Geology and Mineral Resources ........................................................................................... 18 1.13.2 Mineral Reserves and Mining Method ................................................................................... 18 1.13.3 Mineral Processing and Metallurgical Testing ....................................................................... 18 1.13.4 Infrastructure ......................................................................................................................... 19 1.13.5 Environmental, Permitting, Social, and Closure .................................................................... 19 1.13.6 Capital and Operating Costs ................................................................................................. 20 1.13.7 Economics ............................................................................................................................. 21 2 Introduction ................................................................................................................ 22 2.1 Terms of Reference and Purpose ..................................................................................................... 22 2.2 Sources of Information ...................................................................................................................... 22 2.3 Details of Inspection .......................................................................................................................... 22 2.4 Report Version Update ...................................................................................................................... 23 2.5 Qualified Persons .............................................................................................................................. 23 2.6 Forward-Looking Information ............................................................................................................ 23 3 Property Description .................................................................................................. 25 3.1 Property Area .................................................................................................................................... 25 3.2 Mineral Title ....................................................................................................................................... 28 3.3 Encumbrances .................................................................................................................................. 30 3.4 Royalties or Similar Interest .............................................................................................................. 30 4 Accessibility, Climate, Local Resources, Infrastructure, and Physiography ....... 32 SRK Consulting (U.S.), Inc. SEC Technical Report Summary – Salar de Atacama Page ii SalardeAtacama_SECUpdate_Report_USPR002291_Rev03.docx February 2026 4.1 Topography, Elevation, and Vegetation ............................................................................................ 32 4.2 Means of Access ............................................................................................................................... 32 4.3 Climate and Length of Operating Season ......................................................................................... 33 4.4 Infrastructure Availability and Sources .............................................................................................. 34 5 History ......................................................................................................................... 35 5.1 Previous Operations .......................................................................................................................... 35 5.2 Exploration and Development of Previous Owners or Operators ..................................................... 36 6 Geological Setting, Mineralization, and Deposit ..................................................... 40 6.1 Regional, Local, and Property Geology ............................................................................................ 40 6.1.1 Regional Geology .................................................................................................................. 40 6.1.2 Local Geology ....................................................................................................................... 43 6.1.3 Property Geology .................................................................................................................. 43 6.2 Mineral Deposit ................................................................................................................................. 54 6.3 Stratigraphic Column ......................................................................................................................... 54 7 Exploration ................................................................................................................. 56 7.1 Exploration Work (Other Than Drilling) ............................................................................................. 56 7.1.1 TEM Survey ........................................................................................................................... 57 7.1.2 Seismic Reflection ................................................................................................................. 58 7.1.3 Borehole Geophysics ............................................................................................................ 58 7.1.4 Nuclear Magnetic Resonance ............................................................................................... 61 7.1.5 Significant Results and Interpretation ................................................................................... 61 7.2 Exploration Drilling ............................................................................................................................ 61 7.2.1 Drilling Type and Extent ........................................................................................................ 61 7.2.2 Drilling Campaigns ................................................................................................................ 62 7.2.3 Drilling Results and Interpretation ......................................................................................... 65 7.3 Hydraulic Tests ................................................................................................................................. 65 7.3.1 2016 Campaign ..................................................................................................................... 65 7.3.2 2018 to 2019 Testing Campaign ........................................................................................... 68 7.3.3 2020 to 2023 Testing Campaign. .......................................................................................... 69 7.3.4 Packer Testing Campaign ..................................................................................................... 70 7.3.5 Pumping Test Reanalysis by SRK in 2020 ........................................................................... 71 7.3.6 Data Summary ...................................................................................................................... 71 7.4 Brine Sampling .................................................................................................................................. 72 8 Sample Preparation, Analysis, and Security ........................................................... 76 8.1 Sample Collection ............................................................................................................................. 76 8.1.1 Historical Sampling ................................................................................................................ 76 8.1.2 2025 Campaign ..................................................................................................................... 77 SRK Consulting (U.S.), Inc. SEC Technical Report Summary – Salar de Atacama Page iii SalardeAtacama_SECUpdate_Report_USPR002291_Rev03.docx February 2026 8.2 Sample Preparation, Assaying, and Analytical Procedures .............................................................. 79 8.2.1 Historical Sampling ................................................................................................................ 79 8.2.2 2025 Campaign ..................................................................................................................... 79 8.3 QA/QC Procedures ........................................................................................................................... 83 8.3.1 Control Laboratories .............................................................................................................. 83 8.3.2 Correlation Between Lithium Grades of Different Invariant Laboratories of the Sampling Type ....................................................................................................................................... 83 8.3.3 Standards, Blanks, and Duplicates ....................................................................................... 86 8.4 Opinion on Adequacy ........................................................................................................................... 88 9 Data Verification ......................................................................................................... 90 9.1 Data Verification Procedures ............................................................................................................ 90 9.2 Limitations ......................................................................................................................................... 91 9.3 Opinion on Data Adequacy ............................................................................................................... 91 10 Mineral Processing and Metallurgical Testing ........................................................ 93 10.1 Metallurgical Test Work and Analysis ............................................................................................... 93 10.1.1 Bischofite Treatment Testing................................................................................................. 93 10.1.2 Lithium-Carnallite Treatment Testing .................................................................................... 94 10.1.3 SYIP Test Commentary ......................................................................................................... 95 10.2 Opinion on Adequacy ........................................................................................................................ 95 11 Mineral Resource Estimates ..................................................................................... 96 11.1 Key Assumptions, Parameters, and Methods Used ......................................................................... 96 11.1.1 Geological Model ................................................................................................................... 96 11.1.2 Exploratory Data Analysis ..................................................................................................... 99 11.1.3 Drainable Porosity or Specific Yield .................................................................................... 101 11.2 Mineral Resource Estimates ........................................................................................................... 104 11.2.1 Domains .............................................................................................................................. 104 11.2.2 Capping and Compositing ................................................................................................... 105 11.2.3 Spatial Continuity Analysis .................................................................................................. 109 11.2.4 Block Model ......................................................................................................................... 110 11.2.5 Estimation Methodology ...................................................................................................... 111 11.2.6 Estimate Validation .............................................................................................................. 115 11.3 CoG Estimates ................................................................................................................................ 118 11.4 Resources Classification and Criteria ............................................................................................. 118 11.5 Uncertainty ...................................................................................................................................... 119 11.6 Summary Mineral Resources .......................................................................................................... 120 11.7 Recommendations and Opinion ...................................................................................................... 123 12 Mineral Reserve Estimates ...................................................................................... 124

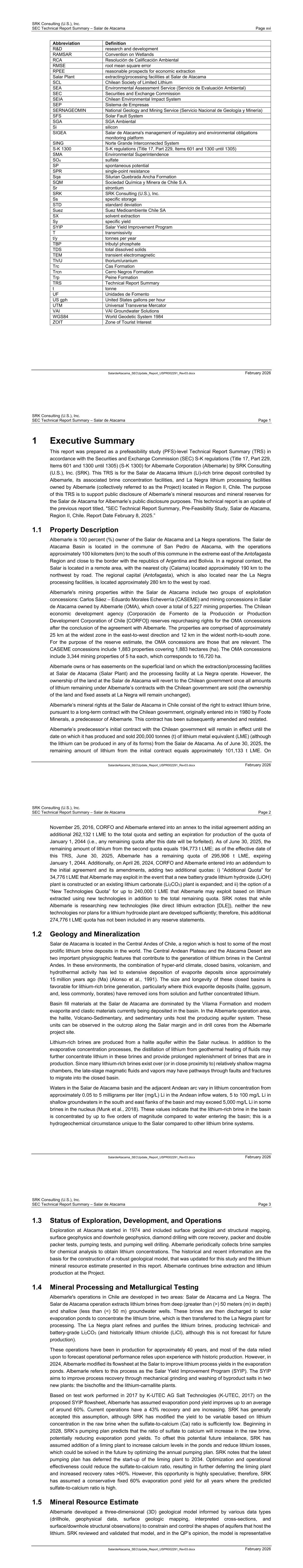

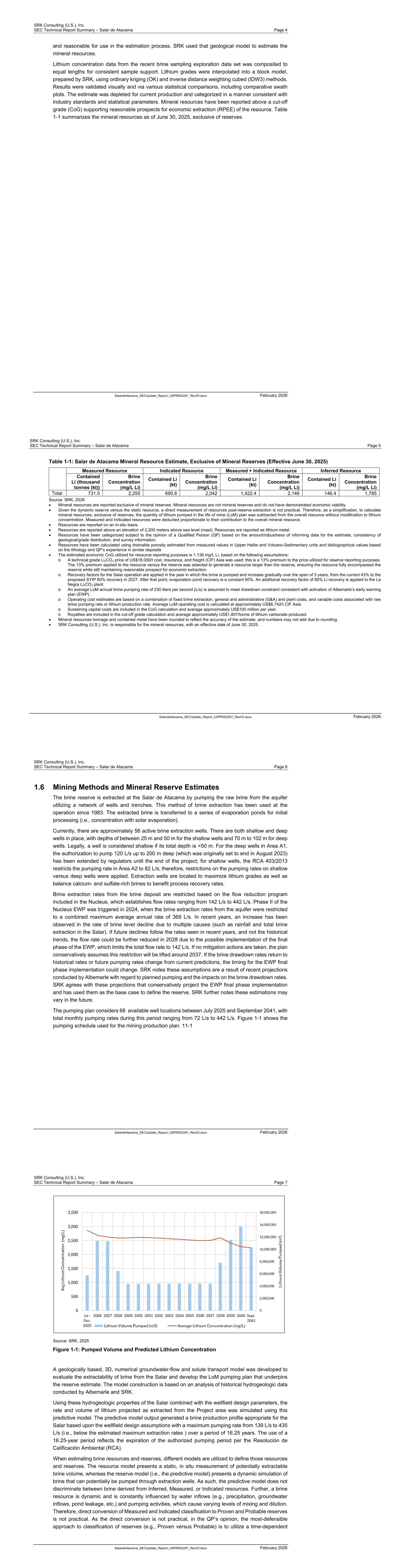

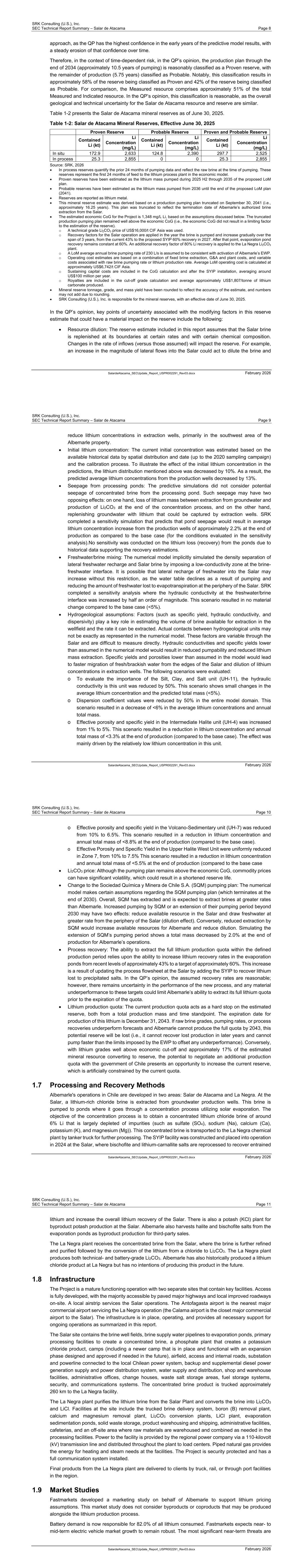

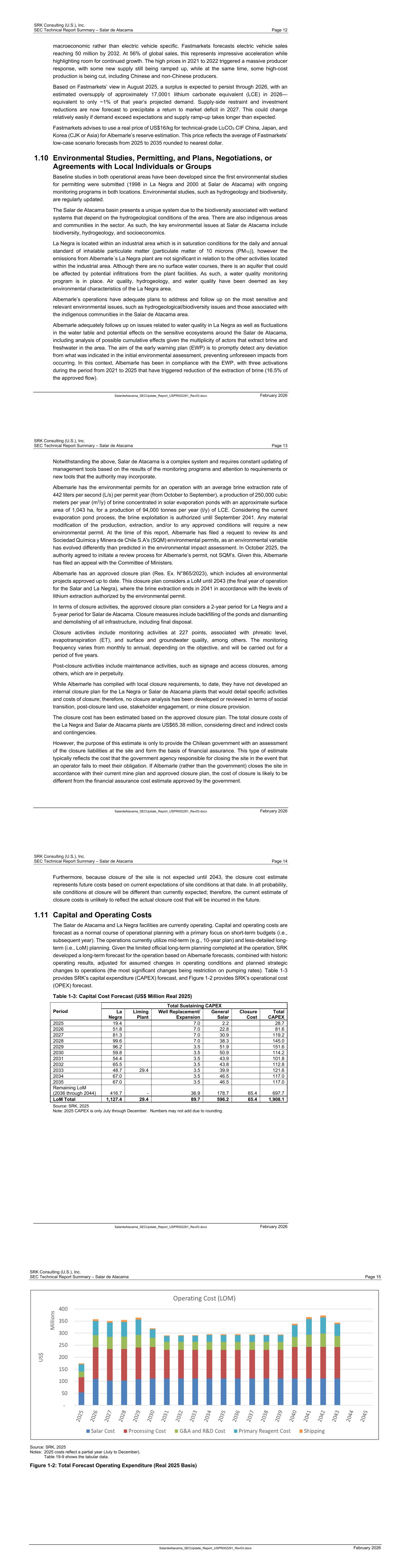

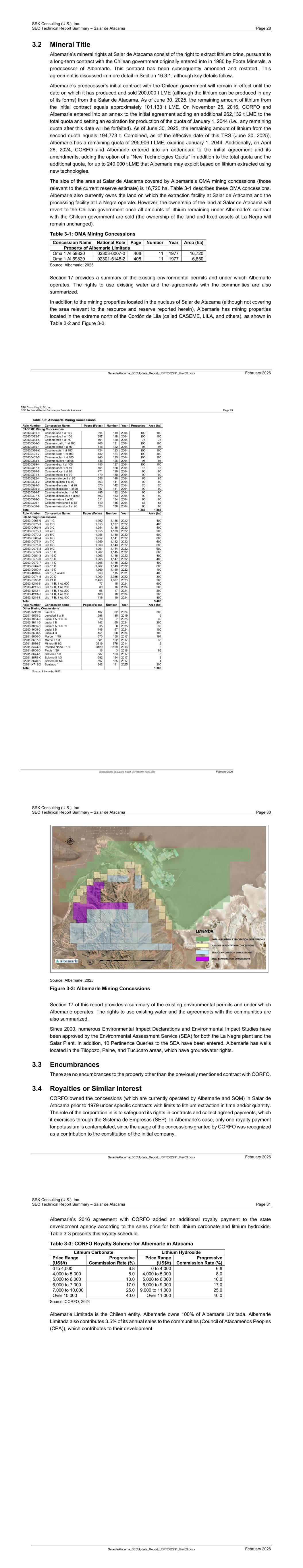

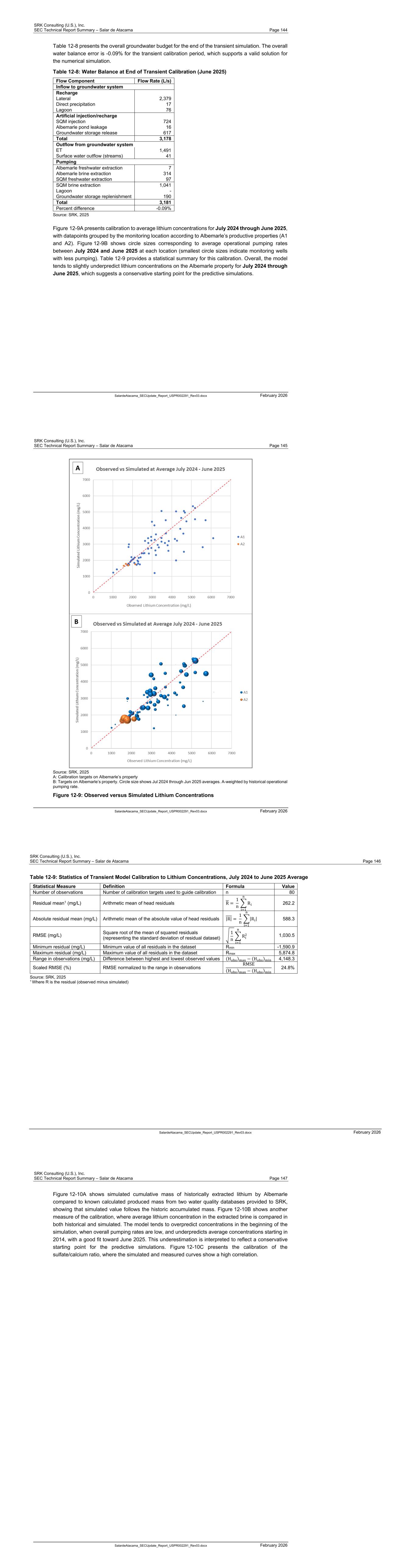

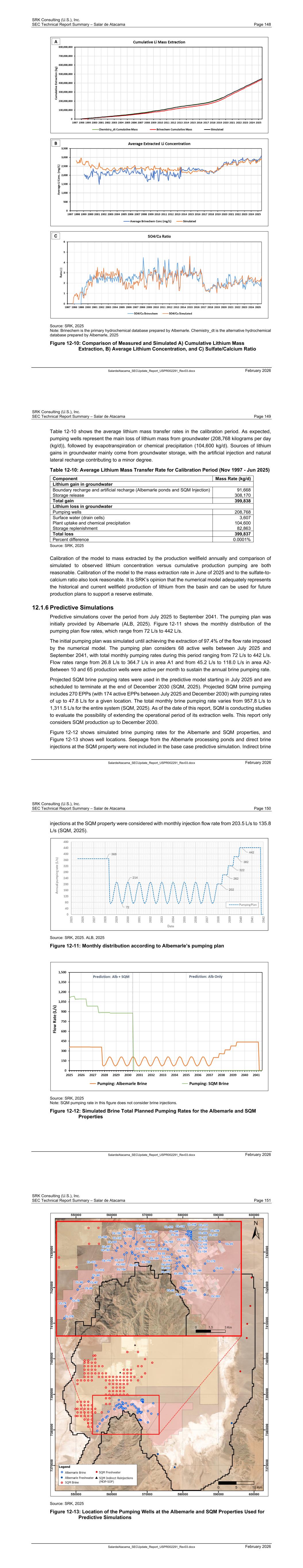

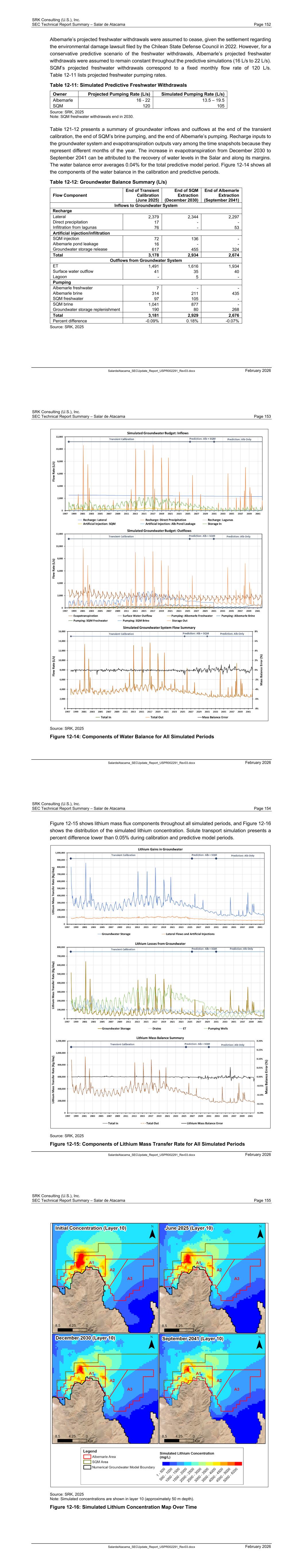

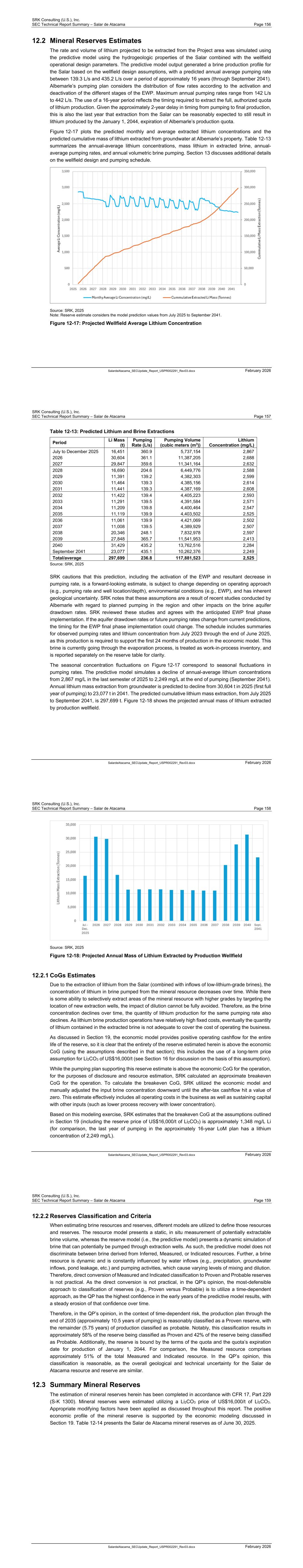

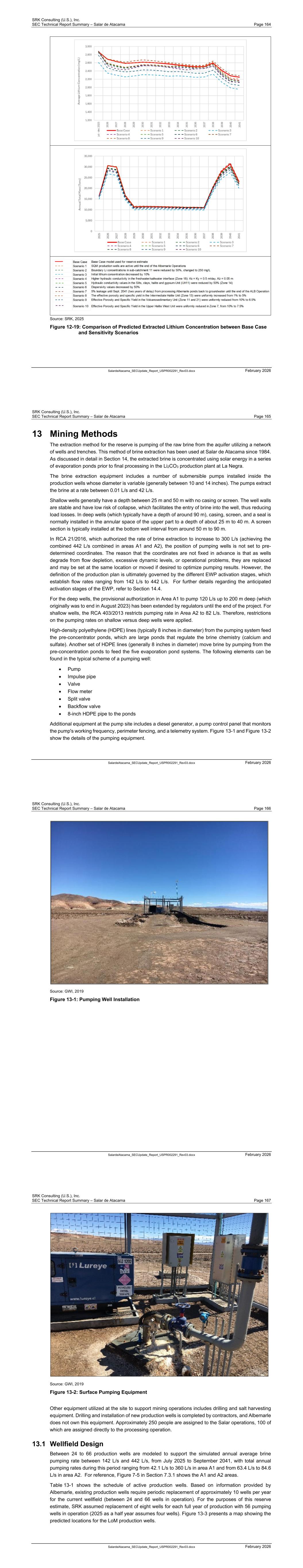

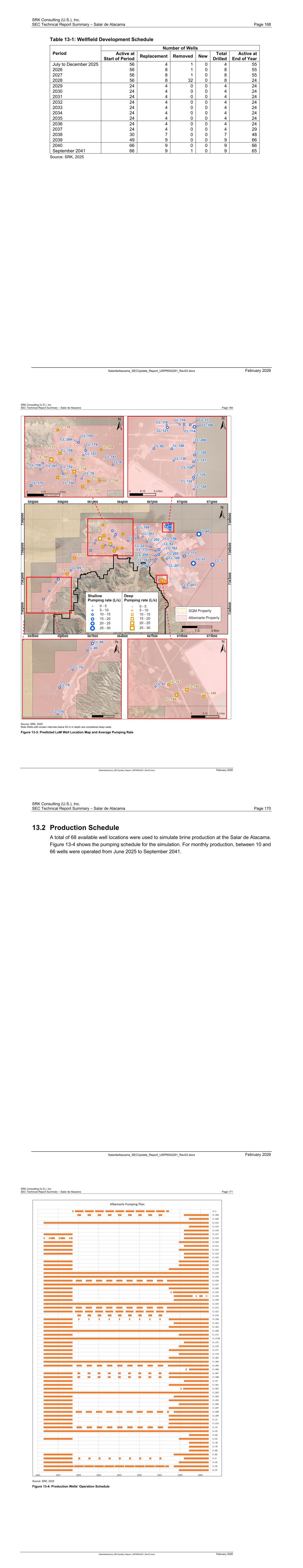

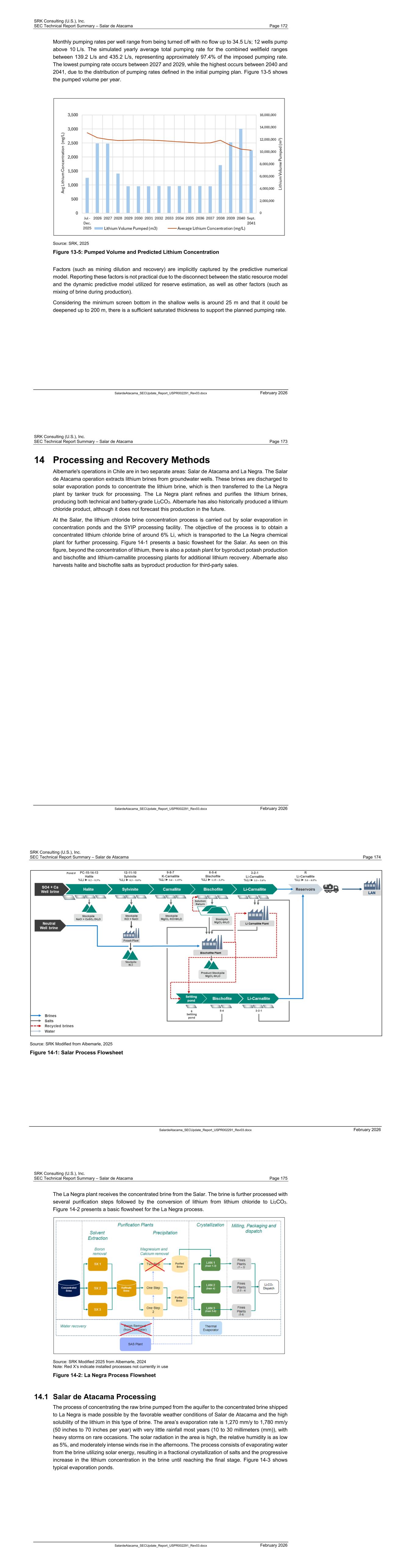

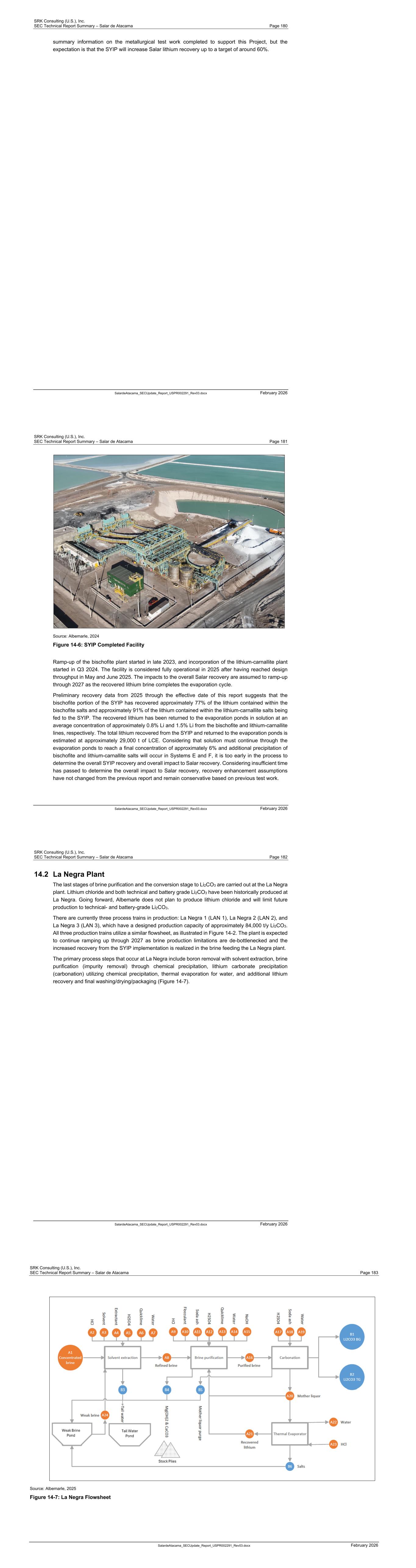

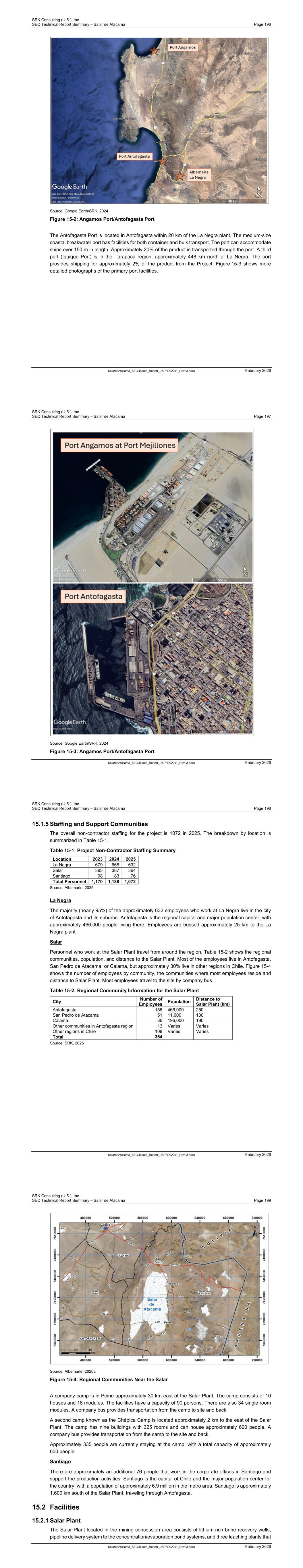

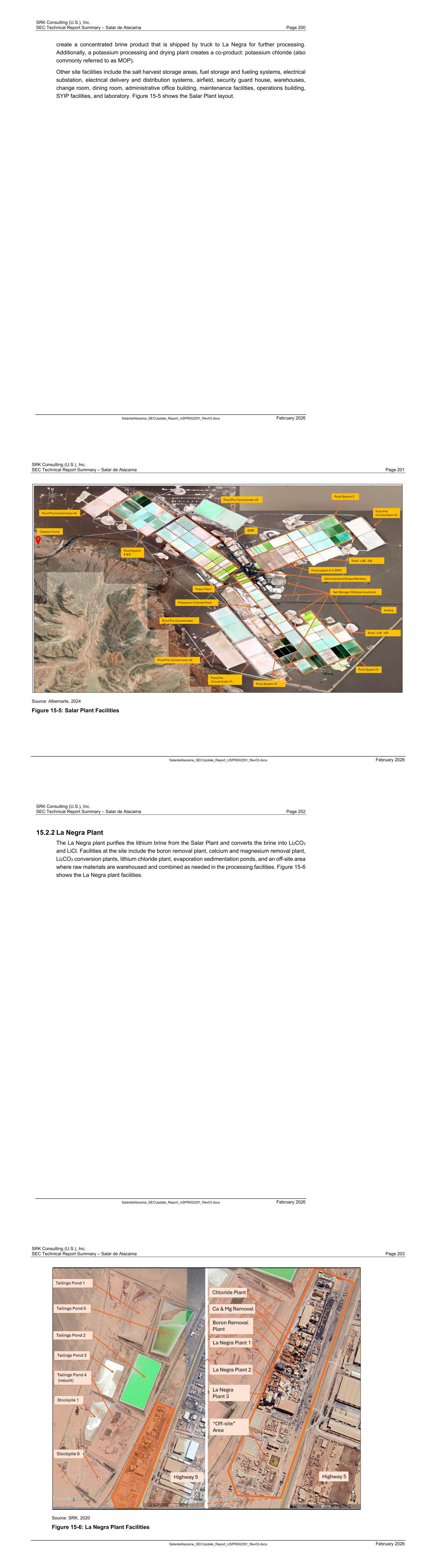

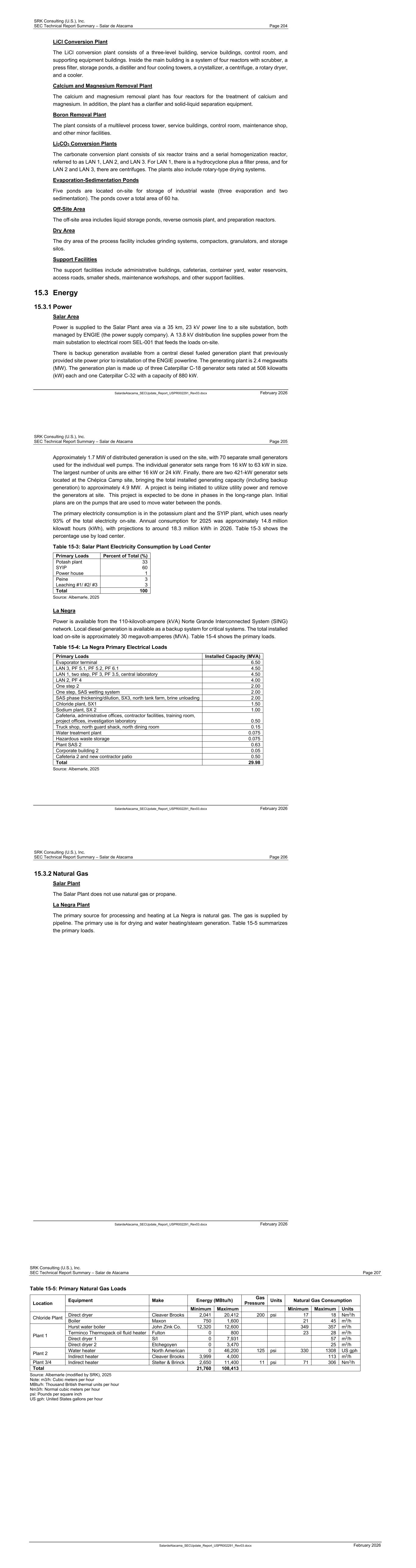

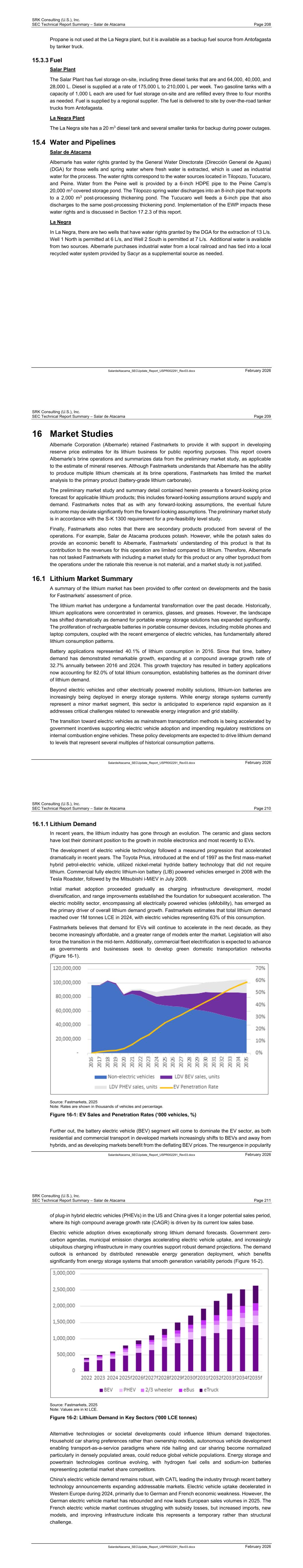

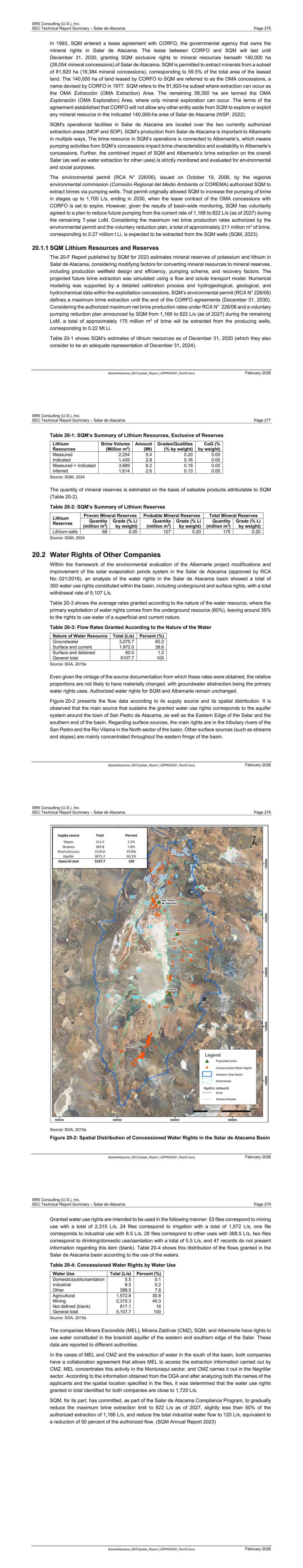

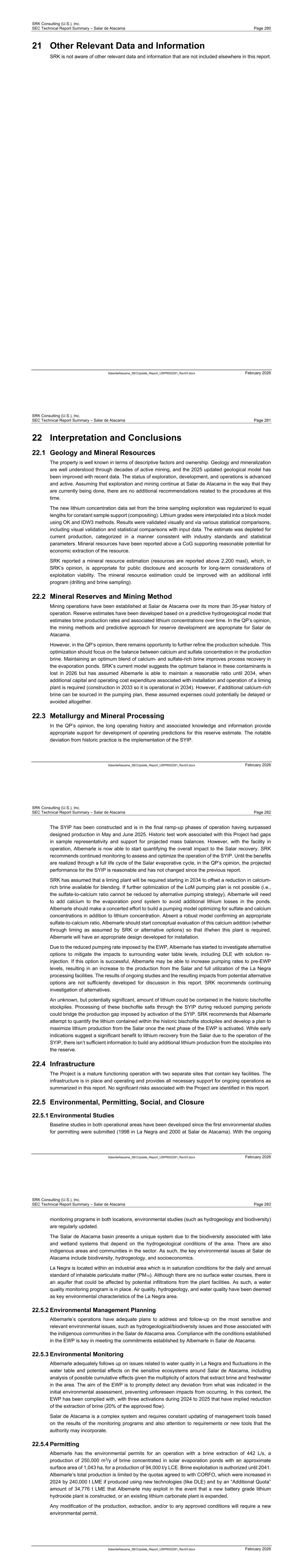

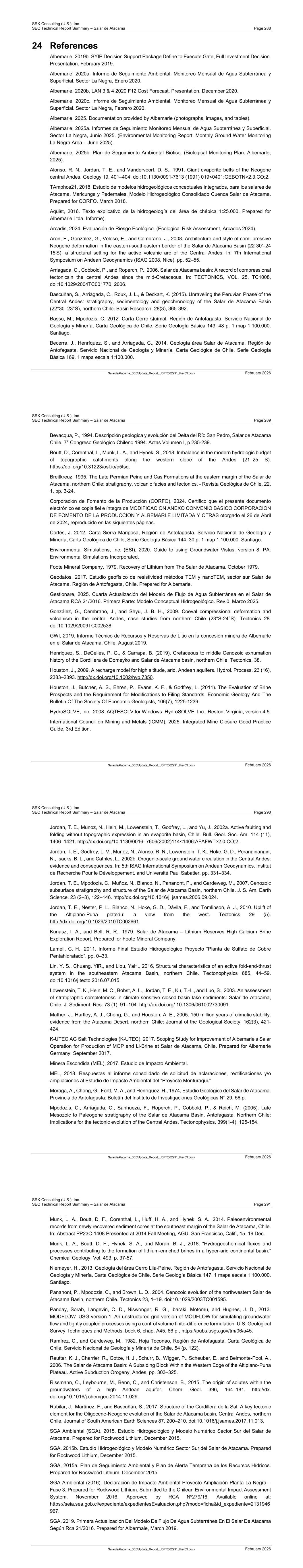

SRK Consulting (U.S.), Inc. SEC Technical Report Summary – Salar de Atacama Page iv SalardeAtacama_SECUpdate_Report_USPR002291_Rev03.docx February 2026 12.1 Key Assumptions, Parameters, and Methods Used ....................................................................... 124 12.1.1 Numerical Groundwater Model............................................................................................ 124 12.1.2 Model Domain and Grid ...................................................................................................... 124 12.1.3 Flow Boundary Conditions .................................................................................................. 125 12.1.4 Hydraulic and Solute Transport Properties ......................................................................... 132 12.1.5 Model Calibration ................................................................................................................ 137 12.1.6 Predictive Simulations ......................................................................................................... 149 12.2 Mineral Reserves Estimates ........................................................................................................... 156 12.2.1 CoGs Estimates .................................................................................................................. 158 12.2.2 Reserves Classification and Criteria ................................................................................... 159 12.3 Summary Mineral Reserves ............................................................................................................ 159 13 Mining Methods ........................................................................................................ 165 13.1 Wellfield Design .............................................................................................................................. 167 13.2 Production Schedule ....................................................................................................................... 170 14 Processing and Recovery Methods........................................................................ 173 14.1 Salar de Atacama Processing ......................................................................................................... 175 14.1.1 Solar Evaporation ................................................................................................................ 176 14.1.2 SYIP .................................................................................................................................... 179 14.2 La Negra Plant ................................................................................................................................ 182 14.2.1 Boron Removal .................................................................................................................... 184 14.2.2 Calcium and Magnesium Removal ..................................................................................... 186 14.2.3 Li2CO3 Precipitation (Carbonation) and Packaging ............................................................. 188 14.2.4 Thermal Evaporation ........................................................................................................... 190 14.3 DLE ................................................................................................................................................. 191 14.4 Process Design Parameters ........................................................................................................... 191 14.4.1 Process Consumables ........................................................................................................ 192 14.5 SRK Opinion ................................................................................................................................... 193 15 Infrastructure ............................................................................................................ 194 15.1 Access, Roads, and Local Communities ........................................................................................ 194 15.1.1 Access ................................................................................................................................. 194 15.1.2 Airport .................................................................................................................................. 195 15.1.3 Rail ...................................................................................................................................... 195 15.1.4 Port Facilities ....................................................................................................................... 195 15.1.5 Staffing and Support Communities ..................................................................................... 198 15.2 Facilities .......................................................................................................................................... 199 15.2.1 Salar Plant ........................................................................................................................... 199 15.2.2 La Negra Plant .................................................................................................................... 202 SRK Consulting (U.S.), Inc. SEC Technical Report Summary – Salar de Atacama Page v SalardeAtacama_SECUpdate_Report_USPR002291_Rev03.docx February 2026 15.3 Energy ............................................................................................................................................. 204 15.3.1 Power .................................................................................................................................. 204 15.3.2 Natural Gas ......................................................................................................................... 206 15.3.3 Fuel ...................................................................................................................................... 208 15.4 Water and Pipelines ........................................................................................................................ 208 16 Market Studies ......................................................................................................... 209 16.1 Lithium Market Summary ................................................................................................................ 209 16.1.1 Lithium Demand .................................................................................................................. 210 16.1.2 Lithium Supply ..................................................................................................................... 213 16.1.3 Lithium Supply-Demand Balance ........................................................................................ 215 16.1.4 Lithium Prices ...................................................................................................................... 216 16.1.5 Lithium battery material prices (Technical grade, spot, CIF CJK, $/kg) .............................. 217 16.2 Product Sales .................................................................................................................................. 220 16.3 Contracts ......................................................................................................................................... 222 16.3.1 CCHEN and CORFO Agreements ...................................................................................... 222 17 Environmental Studies, Permitting, and Plans, Negotiations, or Agreements with Local Individuals or Groups .................................................................................... 225 17.1 Environmental Studies .................................................................................................................... 225 17.1.1 General Background ........................................................................................................... 225 17.1.2 La Negra .............................................................................................................................. 226 17.1.3 Salar de Atacama ................................................................................................................ 228 17.1.4 Tailing Disposal ................................................................................................................... 233 17.1.5 Waste Management ............................................................................................................ 234 17.1.6 Water Management ............................................................................................................. 235 17.1.7 Monitoring ............................................................................................................................ 236 17.1.8 Air Quality ............................................................................................................................ 241 17.1.9 Human Health and Safety ................................................................................................... 241 17.2 Project Permitting ............................................................................................................................ 242 17.2.1 Environmental Permits ........................................................................................................ 242 17.2.2 Operating Permits ............................................................................................................... 244 17.2.3 Water Rights ........................................................................................................................ 246 17.3 Plans, Negotiations, or Agreements ............................................................................................... 246 17.3.1 La Negra .............................................................................................................................. 246 17.3.2 Salar de Atacama ................................................................................................................ 246 17.4 Mine Reclamation and Closure ....................................................................................................... 247 17.4.1 Closure Planning ................................................................................................................. 247 17.4.2 Closure Cost Estimate ......................................................................................................... 249 SRK Consulting (U.S.), Inc. SEC Technical Report Summary – Salar de Atacama Page vi SalardeAtacama_SECUpdate_Report_USPR002291_Rev03.docx February 2026 17.4.3 Performance or Reclamation Bonding ................................................................................ 250 17.4.4 Limitations on the Cost Estimate ......................................................................................... 253 17.5 Plan Adequacy ................................................................................................................................ 253 17.6 Local Procurement .......................................................................................................................... 254 18 Capital and Operating Costs ................................................................................... 255 18.1 Capital Cost Estimates .................................................................................................................... 255 18.2 Operating Cost Estimates ............................................................................................................... 256 19 Economic Analysis .................................................................................................. 259 19.1 General Description ........................................................................................................................ 259 19.1.1 Basic Model Parameters ..................................................................................................... 259 19.1.2 External Factors .................................................................................................................. 259 19.1.3 Technical Factors ................................................................................................................ 260 19.2 Results ............................................................................................................................................ 270 19.3 Sensitivity Analysis .......................................................................................................................... 273 20 Adjacent Properties ................................................................................................. 274 20.1 Adjacent Production ........................................................................................................................ 274 20.1.1 SQM Lithium Resources and Reserves .............................................................................. 276 20.2 Water Rights of Other Companies .................................................................................................. 277 21 Other Relevant Data and Information ..................................................................... 280 22 Interpretation and Conclusions .............................................................................. 281 22.1 Geology and Mineral Resources ..................................................................................................... 281 22.2 Mineral Reserves and Mining Method ............................................................................................ 281 22.3 Metallurgy and Mineral Processing ................................................................................................. 281 22.4 Infrastructure ................................................................................................................................... 282 22.5 Environmental, Permitting, Social, and Closure ............................................................................. 282 22.5.1 Environmental Studies ........................................................................................................ 282 22.5.2 Environmental Management Planning ................................................................................ 283 22.5.3 Environmental Monitoring .................................................................................................... 283 22.5.4 Permitting ............................................................................................................................ 283 22.5.5 Closure ................................................................................................................................ 284 22.6 Capital and Operating Costs ........................................................................................................... 284 22.7 Economic Analysis .......................................................................................................................... 284 23 Recommendations ................................................................................................... 285 23.1 Recommended Work Programs ...................................................................................................... 285 23.1.1 Geology, Resources, and Reserves ................................................................................... 285 23.1.2 Mineral Processing and Metallurgical Testing ..................................................................... 285 SRK Consulting (U.S.), Inc. SEC Technical Report Summary – Salar de Atacama Page vii SalardeAtacama_SECUpdate_Report_USPR002291_Rev03.docx February 2026 23.1.3 Environmental/Closure ........................................................................................................ 286 23.2 Recommended Work Program Costs ............................................................................................. 286 24 References ................................................................................................................ 288 25 Reliance on Information Provided by the Registrant ............................................ 293 Signature Page .............................................................................................................. 295 List of Tables Table 1-1: Salar de Atacama Mineral Resource Estimate, Exclusive of Mineral Reserves (Effective June 30, 2025) ...................................................................................................................................................... 5 Table 1-2: Salar de Atacama Mineral Reserves, Effective June 30, 2025 ......................................................... 8 Table 1-3: Capital Cost Forecast (US$ Million Real 2025) ............................................................................... 14 Table 1-4: Indicative Economic Results ........................................................................................................... 16 Table 2-1: Site Visits ......................................................................................................................................... 23 Table 3-1: OMA Mining Concessions ............................................................................................................... 28 Table 3-2: Albemarle Mining Concessions ....................................................................................................... 29 Table 3-3: CORFO Royalty Scheme for Albemarle in Atacama ....................................................................... 31 Table 7-1: Summary of Exploration Work ......................................................................................................... 57 Table 7-2: 2017 through 2023 Drilling Types and Meters ................................................................................ 63 Table 7-3: Summary of Measured Hydraulic Conductivity Values ................................................................... 72 Table 7-4: Summary of Measured Groundwater Storage Values (Sy) ............................................................. 72 Table 8-1: List and Coordinates of Wells Sampled for the 2025 ...................................................................... 78 Table 8-2: Analytical Methods by Laboratory, 2025 Campaign ........................................................................ 81 Table 8-3: List of Samples in the 2025 Campaign ........................................................................................... 82 Table 11-1: Atacama Lithological Units ............................................................................................................ 98 Table 11-2: Drainable Porosity (Specific Yield) Raw Data, Upper Halite West and Volcano-Sedimentary Units ................................................................................................................................................... 101 Table 11-3: Drainable Porosity (Specific Yield) Values Used for Other Lithological Units ............................. 102 Table 11-4: Drainable Porosity (Specific Yield) Estimation Results, Upper Halite West and Volcano- Sedimentary Units ............................................................................................................................. 104 Table 11-5: Comparison of Raw versus Composite Statistics (Non-Weighted) ............................................. 108 Table 11-6: Summary of Atacama Block Model Parameters ......................................................................... 111 Table 11-7: Summary Search Neighborhood Parameters for Specific Yield (Upper Halite West and Volcano- Sedimentary Lithologies) ................................................................................................................... 115 Table 11-8: Summary of Validation Statistics Composites versus Estimation Methods (Lithium-Aquifer Data) .................................................................................................................................................. 116 Table 11-9: Sources and Degree of Uncertainty ............................................................................................ 120 Table 11-10: Salar de Atacama Mineral Resource Estimate, Exclusive of Mineral Reserves (Effective June 30, 2024) .................................................................................................................................................. 122

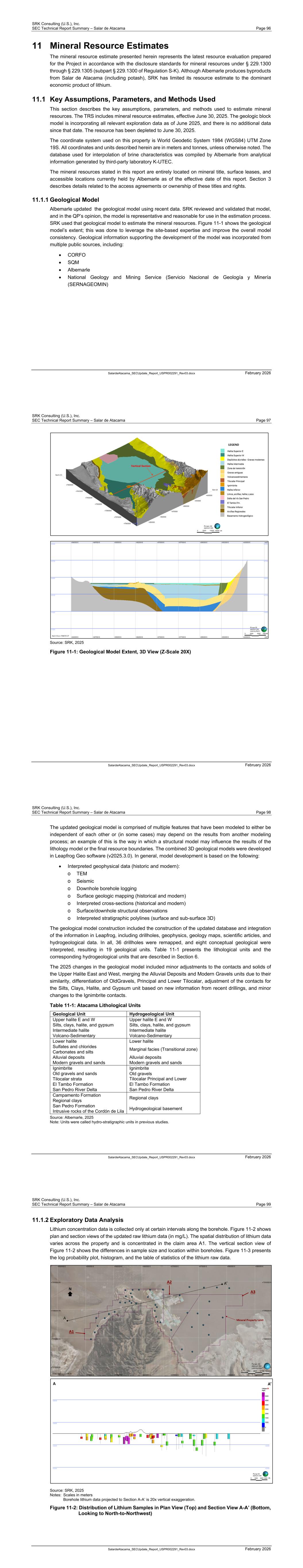

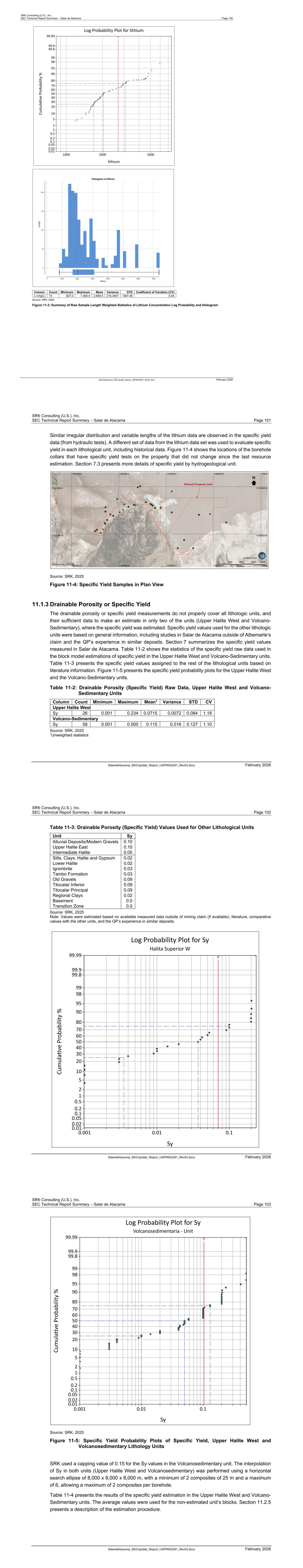

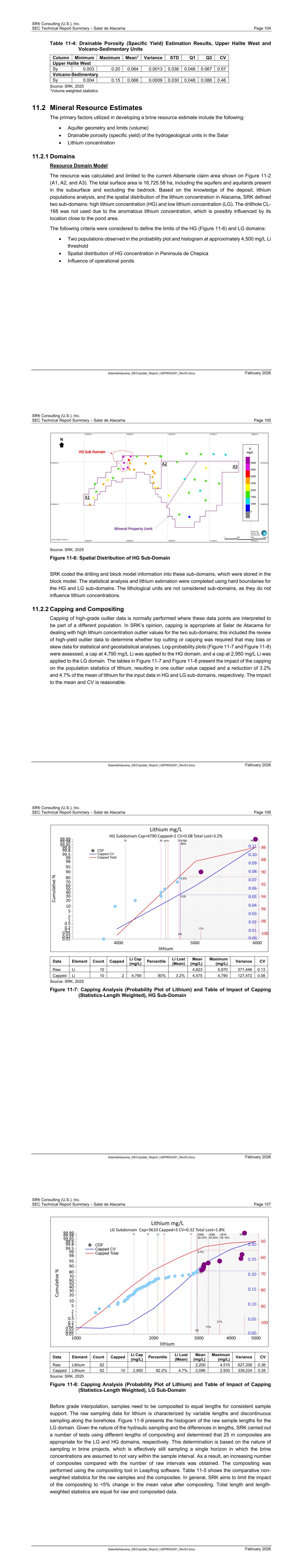

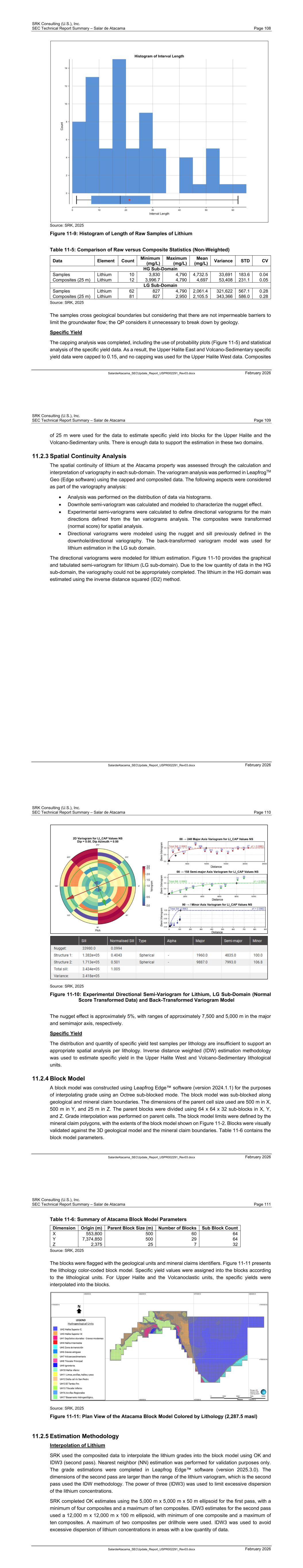

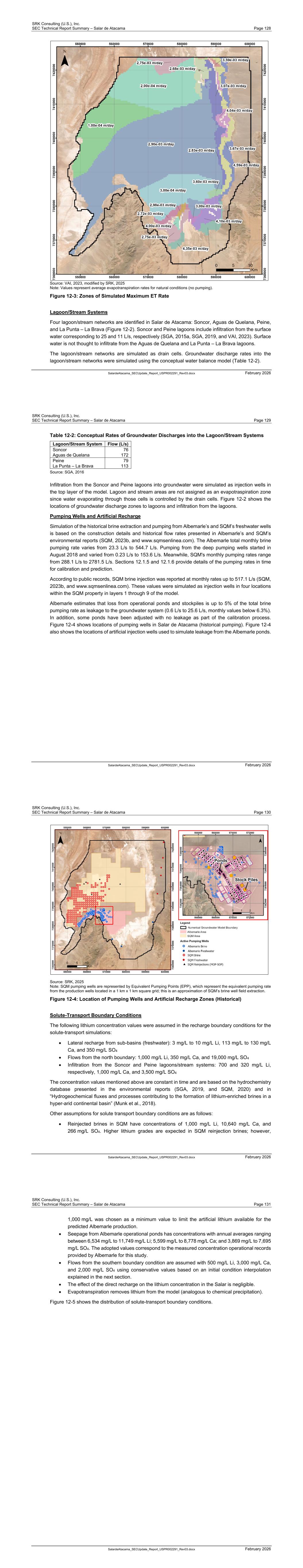

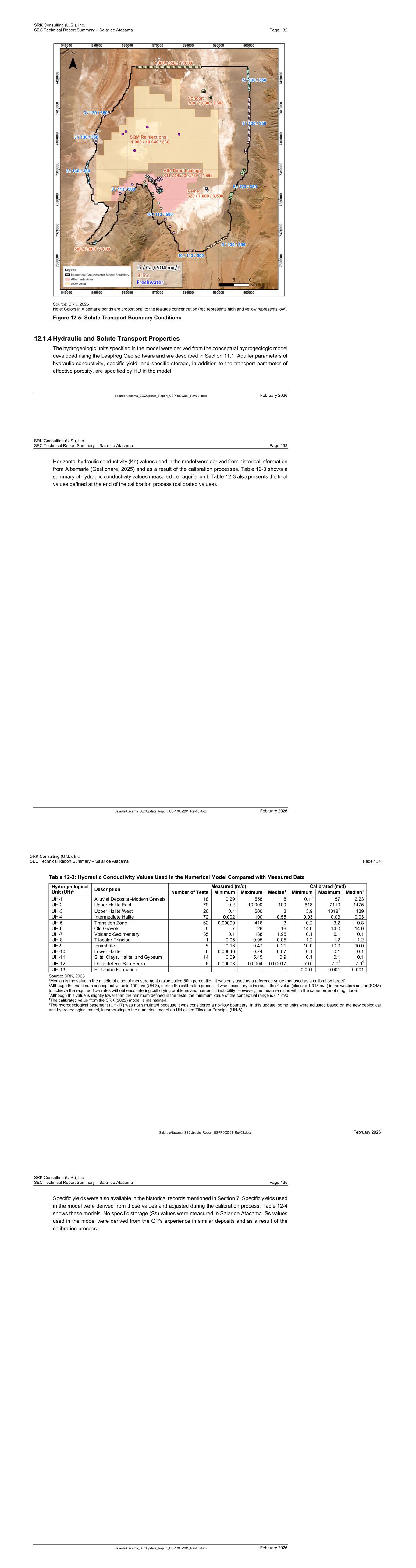

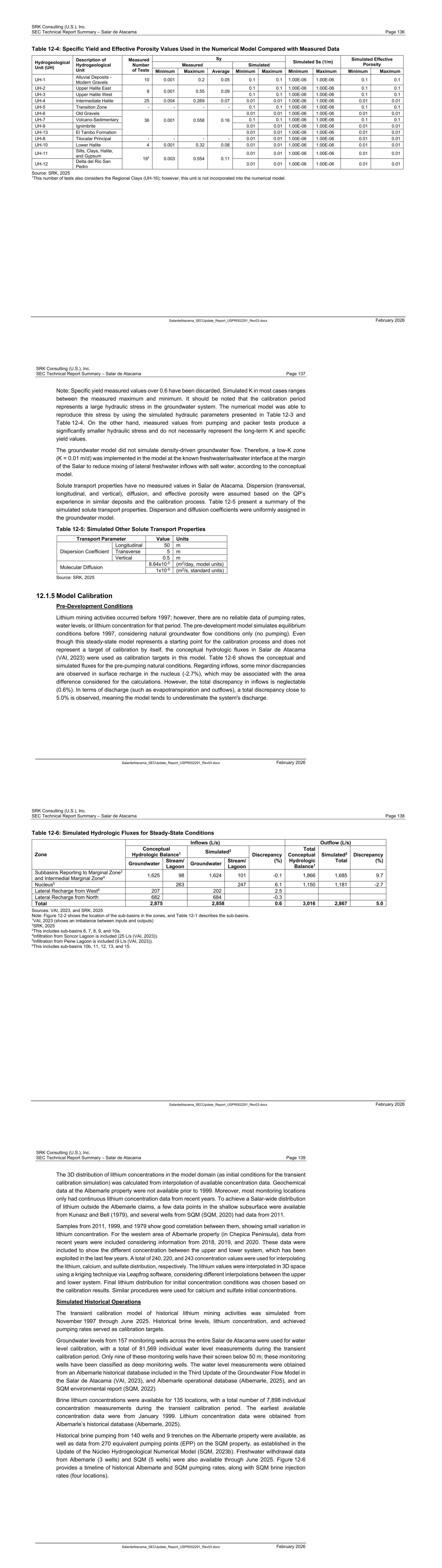

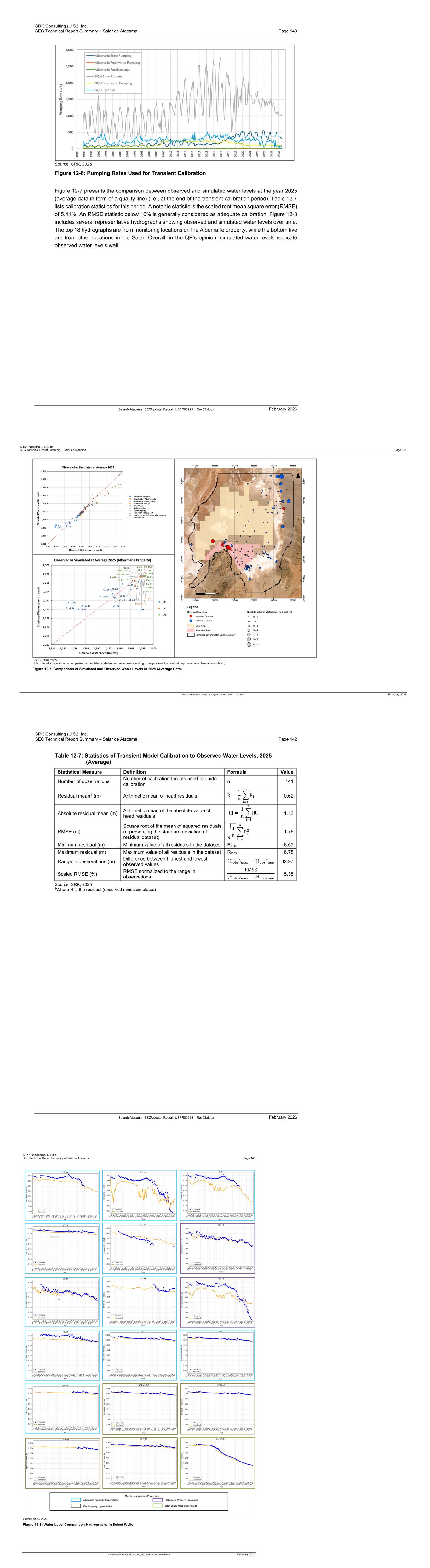

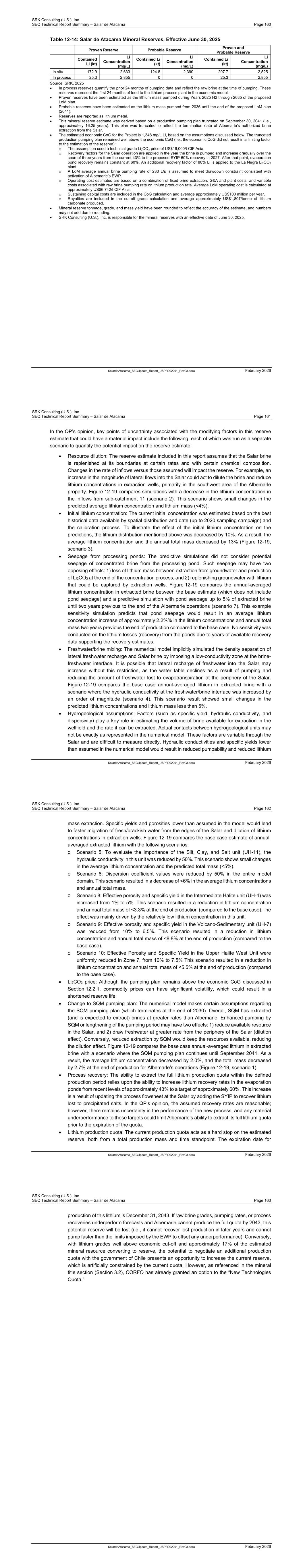

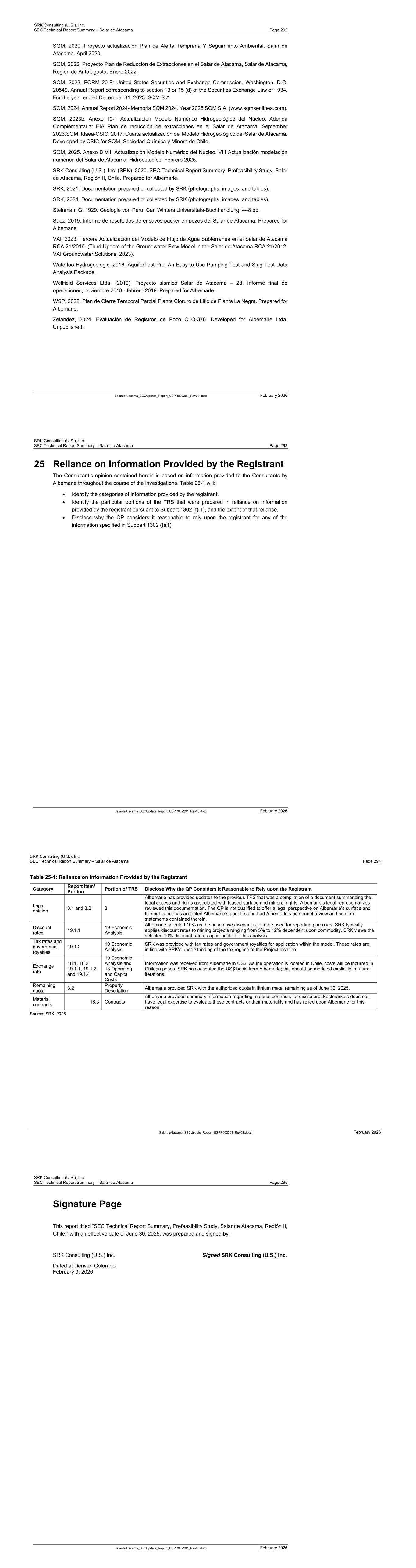

SRK Consulting (U.S.), Inc. SEC Technical Report Summary – Salar de Atacama Page viii SalardeAtacama_SECUpdate_Report_USPR002291_Rev03.docx February 2026 Table 12-1: Recharge Rates and Lateral Inflows Under Natural Conditions ................................................. 127 Table 12-2: Conceptual Rates of Groundwater Discharges into the Lagoon/Stream Systems ..................... 129 Table 12-3: Hydraulic Conductivity Values Used in the Numerical Model Compared with Measured Data .. 134 Table 12-4: Specific Yield and Effective Porosity Values Used in the Numerical Model Compared with Measured Data .................................................................................................................................. 136 Table 12-5: Simulated Other Solute Transport Properties ............................................................................. 137 Table 12-6: Simulated Hydrologic Fluxes for Steady-State Conditions ......................................................... 138 Table 12-7: Statistics of Transient Model Calibration to Observed Water Levels, 2025 (Average) ............... 142 Table 12-8: Water Balance at End of Transient Calibration (June 2025) ....................................................... 144 Table 12-9: Statistics of Transient Model Calibration to Lithium Concentrations, July 2024 to June 2025 Average ............................................................................................................................................. 146 Table 12-10: Average Lithium Mass Transfer Rate for Calibration Period (Nov 1997 - Jun 2025) ................ 149 Table 12-11: Simulated Predictive Freshwater Withdrawals .......................................................................... 152 Table 12-12: Groundwater Balance Summary (L/s) ....................................................................................... 152 Table 12-13: Predicted Lithium and Brine Extractions ................................................................................... 157 Table 12-14: Salar de Atacama Mineral Reserves, Effective June 30, 2025 ................................................. 160 Table 13-1: Wellfield Development Schedule ................................................................................................. 168 Table 14-1: La Negra Mass Balance .............................................................................................................. 184 Table 14-2: Annual Average Salar Extraction Volume ................................................................................... 191 Table 14-3: Current Process Consumables ................................................................................................... 192 Table 15-1: Project Non-Contractor Staffing Summary .................................................................................. 198 Table 15-2: Regional Community Information for the Salar Plant .................................................................. 198 Table 15-3: Salar Plant Electricity Consumption by Load Center .................................................................. 205 Table 15-4: La Negra Primary Electrical Loads .............................................................................................. 205 Table 15-5: Primary Natural Gas Loads ......................................................................................................... 207 Table 16-1: Technical grade Li2CO3 Specifications ........................................................................................ 220 Table 16-2: Battery grade Li2CO3 Specifications ............................................................................................ 221 Table 16-3: Historic La Negra Annual Production Rates ................................................................................ 221 Table 16-4: Current La Negra Production Capacity by Product ..................................................................... 221 Table 16-5: 2025 de Atacama Product Consumption .................................................................................... 222 Table 16-6: CORFO Royalty/Commission Rates ........................................................................................... 224 Table 17-1: La Negra Water Monitoring Parameters ..................................................................................... 237 Table 17-2: Salar de Atacama Environmental Monitoring Points ................................................................... 239 Table 17-3: Salar de Atacama Biodiversity Monitoring Plan .......................................................................... 241 Table 17-4: Albemarle Projects in the Antofagasta Region with Environmental License .............................. 243 Table 17-5: Operational Permits for Albemarle’s La Negra and Salar de Atacama Facilities ........................ 245 Table 17-6: La Negra Plant Facilities ............................................................................................................. 247 Table 17-7: Salar de Atacama Plant Facilities ................................................................................................ 248 SRK Consulting (U.S.), Inc. SEC Technical Report Summary – Salar de Atacama Page ix SalardeAtacama_SECUpdate_Report_USPR002291_Rev03.docx February 2026 Table 17-8: La Negra and Salar de Atacama Closure Costs ......................................................................... 250 Table 18-1: Capital Cost Forecast ($M Real 2025) ........................................................................................ 256 Table 18-2: Key Assumptions, Variable Cost Model ...................................................................................... 257 Table 19-1: Basic Model Parameters ............................................................................................................. 259 Table 19-2: CORFO Royalty Scale ................................................................................................................ 260 Table 19-3: Modeled Life of Operation Pumping Profile ................................................................................ 262 Table 19-4: Life-of-Operation Processing Summary ...................................................................................... 265 Table 19-5: Operating Cost Summary ............................................................................................................ 265 Table 19-6: Variable Processing Costs (2026 Onward) ................................................................................. 268 Table 19-7: R&D Costs ................................................................................................................................... 268 Table 19-8: Indicative Economic Results ....................................................................................................... 270 Table 19-9: Annual Cashflow.......................................................................................................................... 271 Table 20-1: SQM’s Summary of Lithium Resources, Exclusive of Reserves ................................................. 277 Table 20-2: SQM’s Summary of Lithium Reserves ........................................................................................ 277 Table 20-3: Flow Rates Granted According to the Nature of the Water ......................................................... 277 Table 20-4: Concessioned Water Rights by Water Use ................................................................................. 279 Table 23-1: Summary of Costs for Recommended Work ............................................................................... 287 Table 25-1: Reliance on Information Provided by the Registrant ................................................................... 294 List of Figures Figure 1-1: Pumped Volume and Predicted Lithium Concentration ................................................................... 7 Figure 1-2: Total Forecast Operating Expenditure (Real 2025 Basis) ............................................................. 15 Figure 1-3: Annual Cashflow Summary ............................................................................................................ 17 Figure 3-1: Location Map .................................................................................................................................. 25 Figure 3-2: Mining Claims in Salar de Atacama ............................................................................................... 27 Figure 3-3: Albemarle Mining Concessions ...................................................................................................... 30 Figure 4-1: Property Access ............................................................................................................................. 33 Figure 5-1: First Installations, 1981 .................................................................................................................. 36 Figure 5-2: Locations of Wells Drilled during the 1974 to 1979 Campaigns (Foote Mineral Company) .......... 37 Figure 5-3: Locations of TEM and NanoTEM Surveys in the 2013 and 2014 Field Campaign (Rockwood) ... 38 Figure 5-4: Locations of Well and Piezometers Drilled in 2013 and 2014 Field Campaign (Rockwood) ......... 39 Figure 6-1: Regional Geology Map ................................................................................................................... 42 Figure 6-2: Main Structural Features ................................................................................................................ 50 Figure 6-3: Generalized Conceptual Geologic Map ......................................................................................... 52 Figure 6-4: Generalized Conceptual Geologic Cross-Section C – C’ (Map in Figure 6-3) ............................... 53 Figure 6-5: Stratigraphic Column ...................................................................................................................... 55 SRK Consulting (U.S.), Inc. SEC Technical Report Summary – Salar de Atacama Page x SalardeAtacama_SECUpdate_Report_USPR002291_Rev03.docx February 2026 Figure 7-1: Location of Exploration at the Albemarle Atacama ........................................................................ 56 Figure 7-2: Example of Results from the Geophysical Profile TEM ................................................................. 58 Figure 7-3: Example of Geophysical Log in Well CLO-376 .............................................................................. 60 Figure 7-4: Location Map of 2017 to 2024 Drilling Considered to Update the Hydrostratigraphic Model ........ 64 Figure 7-5: Location of the Production Wells Drilled, 2013 through 2016 Campaigns .................................... 66 Figure 7-6: Location of Observation Wells or Piezometers Drilled in the 2013 through 2016 Campaigns ...... 67 Figure 7-7: Location Map of the Long-Term Pumping Tests: Deep Pumping Wells ........................................ 68 Figure 7-8: Location Map of Hydraulic Tests Performed from 2020 to 2023 ................................................... 69 Figure 7-9: Map of the Location of the Wells Tested by the Double Packer System ....................................... 70 Figure 7-10: Historical Sampling Points Location, 1999 to 2019 ...................................................................... 73 Figure 7-11: Measured Lithium Concentration from Historical Database, 1999 to 2025 ................................. 73 Figure 7-12: Sampling Points in the 2018-2019 Campaign .............................................................................. 74 Figure 7-13: Sampled Points in the 2022 Campaign ........................................................................................ 75 Figure 8-1: Historical Lithium Variability, 1999 to 2023 .................................................................................... 77 Figure 8-2: Sampling Points, 2025 Campaign .................................................................................................. 81 Figure 8-3: Scatter Diagram Comparing the Results Obtained for Lithium between Albemarle’s Atacama Salar Plant and K-UTEC Laboratories .......................................................................................................... 84 Figure 8-4: Scatter Diagram Comparing the Results Obtained for Lithium between Albemarle’s Atacama Salar Plant and Alex Stewart Laboratories ................................................................................................... 85 Figure 8-5: Scatter Diagram Comparing the Results Obtained for Lithium between Alex Stewart and K-UTEC Laboratories ......................................................................................................................................... 86 Figure 8-6: Standard Samples .......................................................................................................................... 87 Figure 8-7: Duplicates Samples ....................................................................................................................... 88 Figure 9-1: Comparison of Historical Lithium Concentrations and 2025 Campaign (K-UTEC) ....................... 91 Figure 11-1: Geological Model Extent, 3D View (Z-Scale 20X) ....................................................................... 97 Figure 11-2: Distribution of Lithium Samples in Plan View (Top) and Section View A-A’ (Bottom, Looking to North-to-Northwest) ............................................................................................................................. 99 Figure 11-3: Summary of Raw Sample Length Weighted Statistics of Lithium Concentration Log Probability and Histogram ................................................................................................................................... 100 Figure 11-4: Specific Yield Samples in Plan View .......................................................................................... 101 Figure 11-5: Specific Yield Probability Plots of Specific Yield, Upper Halite West and Volcanosedimentary Lithology Units ................................................................................................................................... 103 Figure 11-6: Spatial Distribution of HG Sub-Domain ...................................................................................... 105 Figure 11-7: Capping Analysis (Probability Plot of Lithium) and Table of Impact of Capping (Statistics-Length Weighted), HG Sub-Domain .............................................................................................................. 106 Figure 11-8: Capping Analysis (Probability Plot of Lithium) and Table of Impact of Capping (Statistics-Length Weighted), LG Sub-Domain .............................................................................................................. 107 Figure 11-9: Histogram of Length of Raw Samples of Lithium ....................................................................... 108 Figure 11-10: Experimental Directional Semi-Variogram for Lithium, LG Sub-Domain (Normal Score Transformed Data) and Back-Transformed Variogram Model .......................................................... 110 SRK Consulting (U.S.), Inc. SEC Technical Report Summary – Salar de Atacama Page xi SalardeAtacama_SECUpdate_Report_USPR002291_Rev03.docx February 2026 Figure 11-11: Plan View of the Atacama Block Model Colored by Lithology (2,287.5 masl) ......................... 111 Figure 11-12: Histogram of Number of Drillholes Used to Estimate the Block Model .................................... 112 Figure 11-13: Histogram of Number of Composites Used to Estimate the Block Model ............................... 113 Figure 11-14: Histogram of Average Distance from Blocks to Composites Used in Estimation .................... 114 Figure 11-15: Example of Visual Validation of Lithium Grades in Composites versus Block Model Horizontal Section, Plan View (2,262.5 masl Elevation) ..................................................................................... 115 Figure 11-16: Lithium (mg/L), LG Domain, Swath Analysis at Atacama (X and Y Coordinates) ................... 117 Figure 11-17: Model Horizontal Section, Plan View, Blocks Colored by Classification (2,280 masl Elevation) ........................................................................................................................................... 119 Figure 12-1: Oblique 3D View of Numerical Groundwater Model .................................................................. 125 Figure 12-2: Zones of Direct Recharge and Lateral Groundwater Inflow ....................................................... 126 Figure 12-3: Zones of Simulated Maximum ET Rate ..................................................................................... 128 Figure 12-4: Location of Pumping Wells and Artificial Recharge Zones (Historical) ...................................... 130 Figure 12-5: Solute-Transport Boundary Conditions ...................................................................................... 132 Figure 12-6: Pumping Rates Used for Transient Calibration .......................................................................... 140 Figure 12-7: Comparison of Simulated and Observed Water Levels in 2025 (Average Data) ...................... 141 Figure 12-8: Water Level Comparison Hydrographs in Select Wells ............................................................. 143 Figure 12-9: Observed versus Simulated Lithium Concentrations ................................................................. 145 Figure 12-10: Comparison of Measured and Simulated A) Cumulative Lithium Mass Extraction, B) Average Lithium Concentration, and C) Sulfate/Calcium Ratio ....................................................................... 148 Figure 12-11: Monthly distribution according to Albemarle’s pumping plan ................................................... 150 Figure 12-12: Simulated Brine Total Planned Pumping Rates for the Albemarle and SQM Properties ........ 150 Figure 12-13: Location of the Pumping Wells at the Albemarle and SQM Properties Used for Predictive Simulations ........................................................................................................................................ 151 Figure 12-14: Components of Water Balance for All Simulated Periods ....................................................... 153 Figure 12-15: Components of Lithium Mass Transfer Rate for All Simulated Periods ................................... 154 Figure 12-16: Simulated Lithium Concentration Map Over Time ................................................................... 155 Figure 12-17: Projected Wellfield Average Lithium Concentration ................................................................. 156 Figure 12-18: Projected Annual Mass of Lithium Extracted by Production Wellfield ..................................... 158 Figure 12-19: Comparison of Predicted Extracted Lithium Concentration between Base Case and Sensitivity Scenarios ........................................................................................................................................... 164 Figure 13-1: Pumping Well Installation ........................................................................................................... 166 Figure 13-2: Surface Pumping Equipment ..................................................................................................... 167 Figure 13-3: Predicted LoM Well Location Map and Average Pumping Rate ................................................ 169 Figure 13-4: Production Wells’ Operation Schedule ...................................................................................... 171 Figure 13-5: Pumped Volume and Predicted Lithium Concentration ............................................................. 172 Figure 14-1: Salar Process Flowsheet ........................................................................................................... 174 Figure 14-2: La Negra Process Flowsheet ..................................................................................................... 175 Figure 14-3: Evaporation Ponds ..................................................................................................................... 176

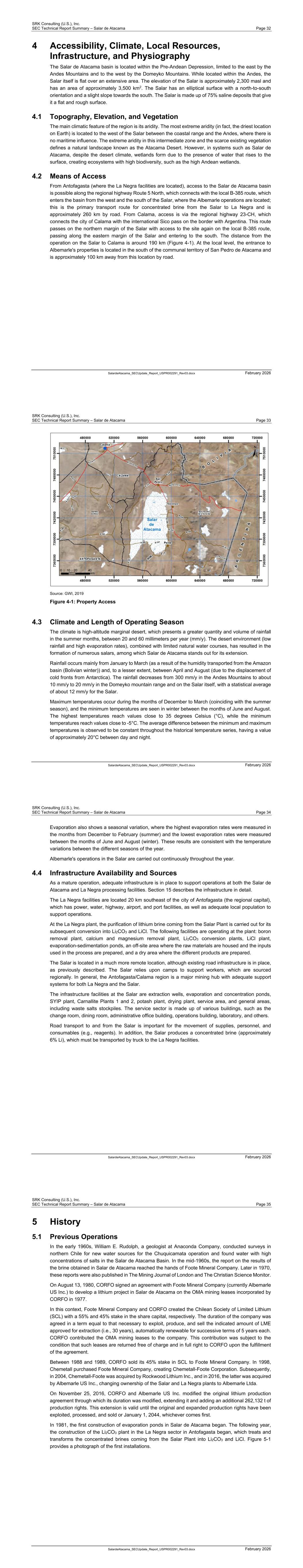

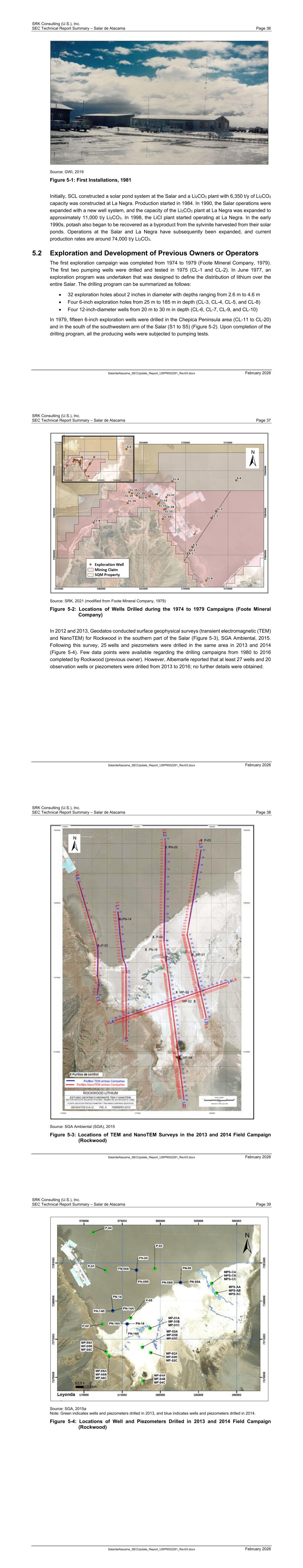

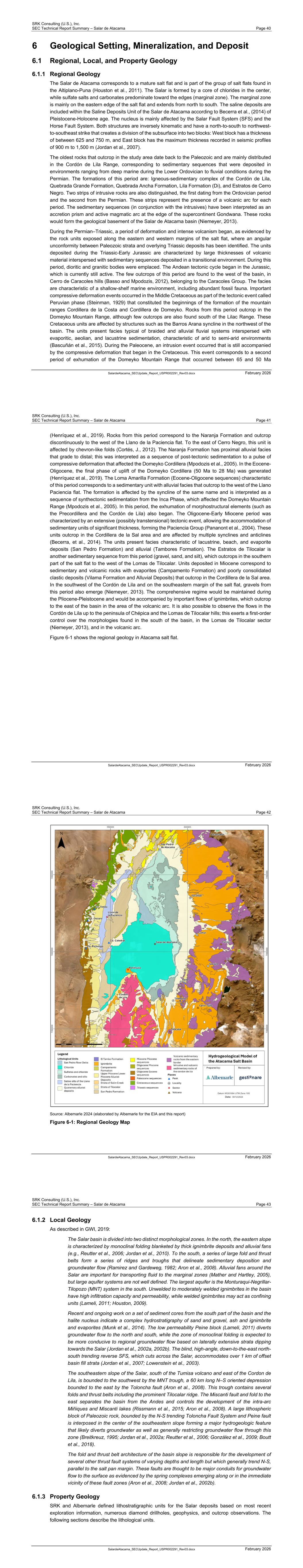

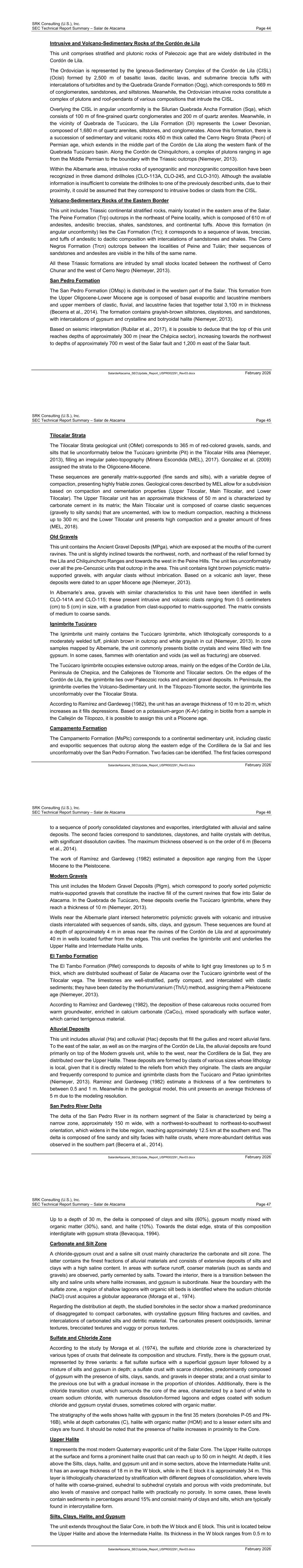

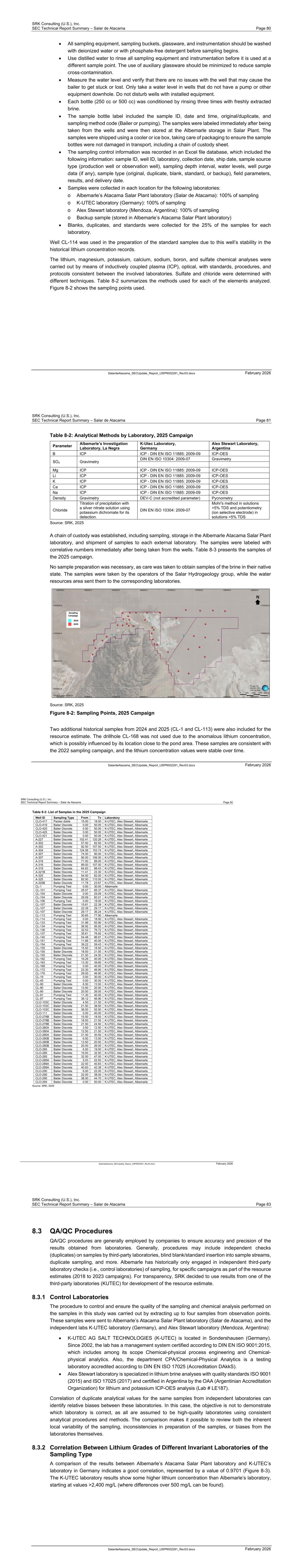

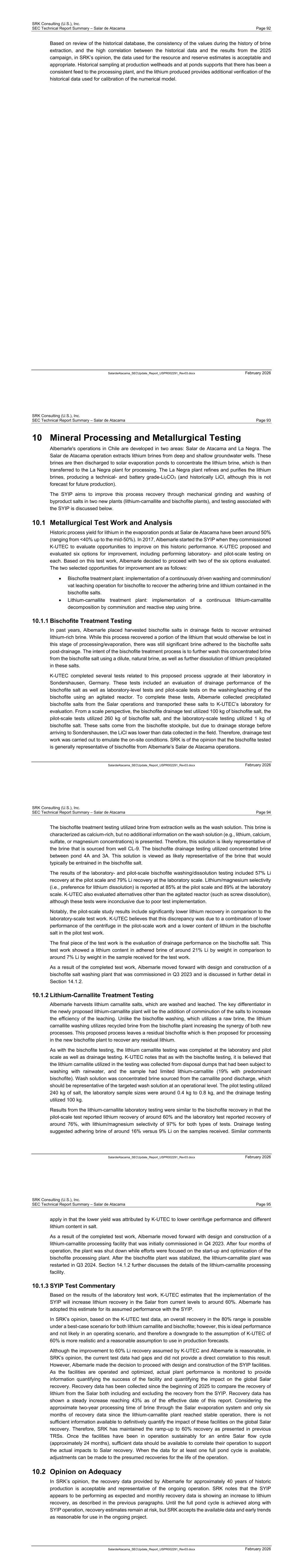

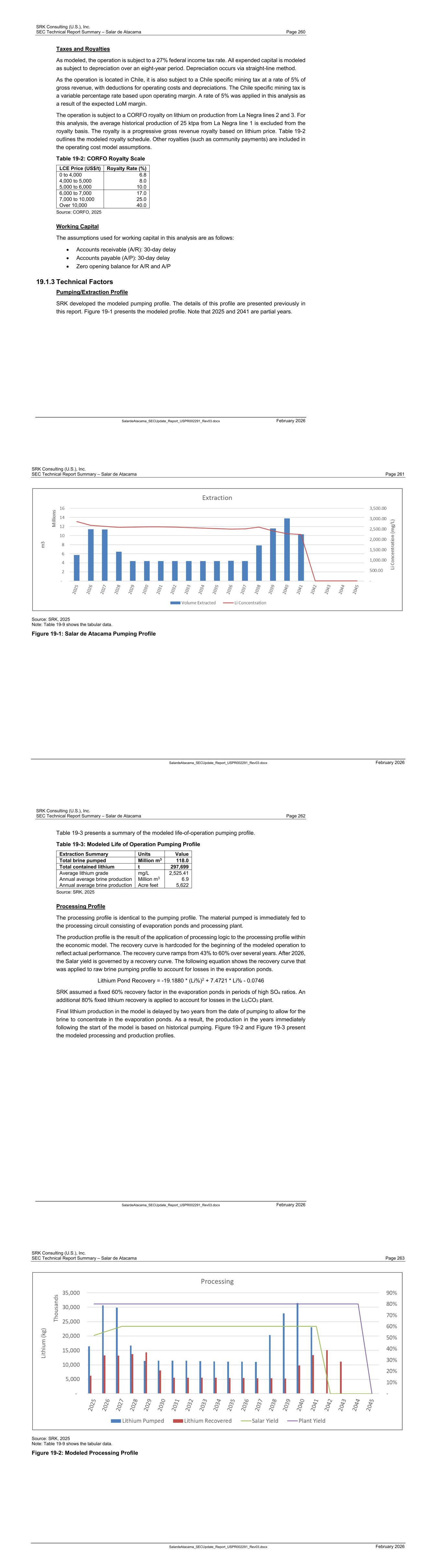

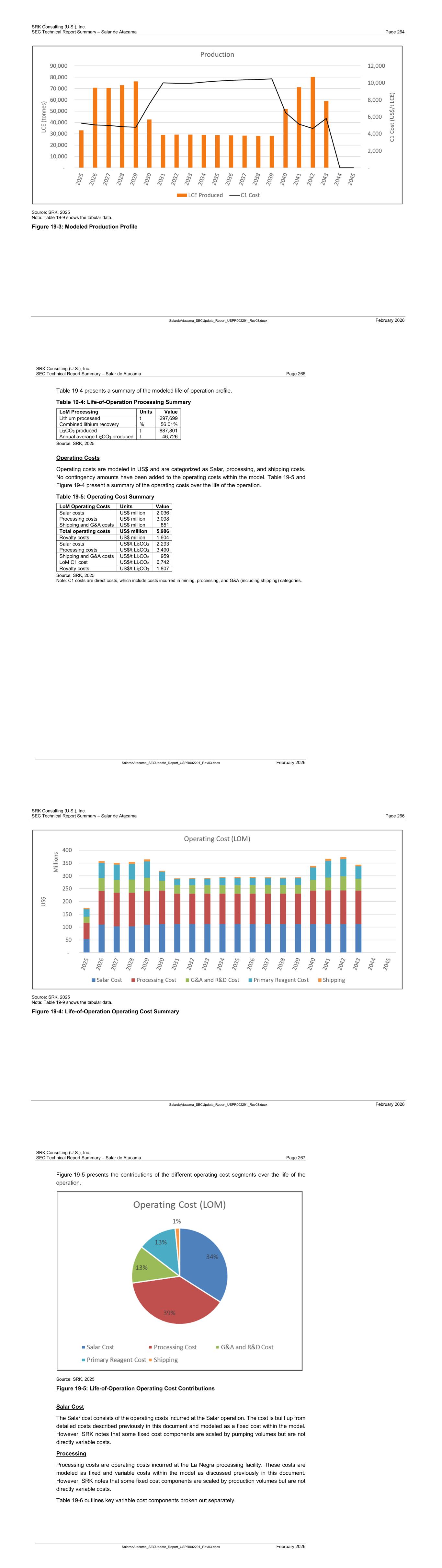

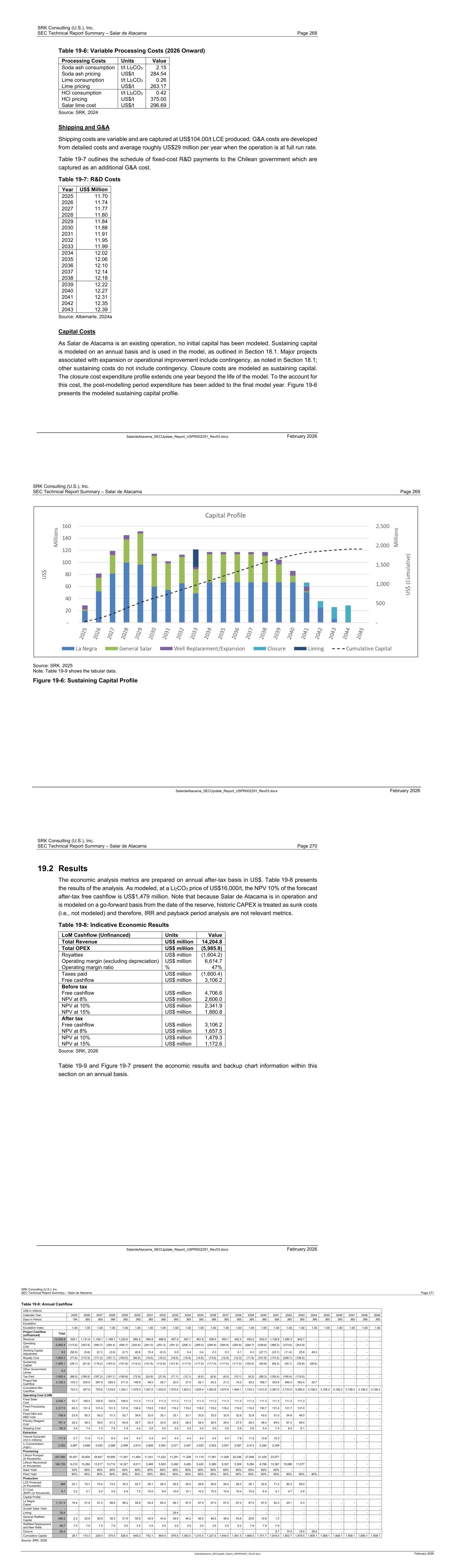

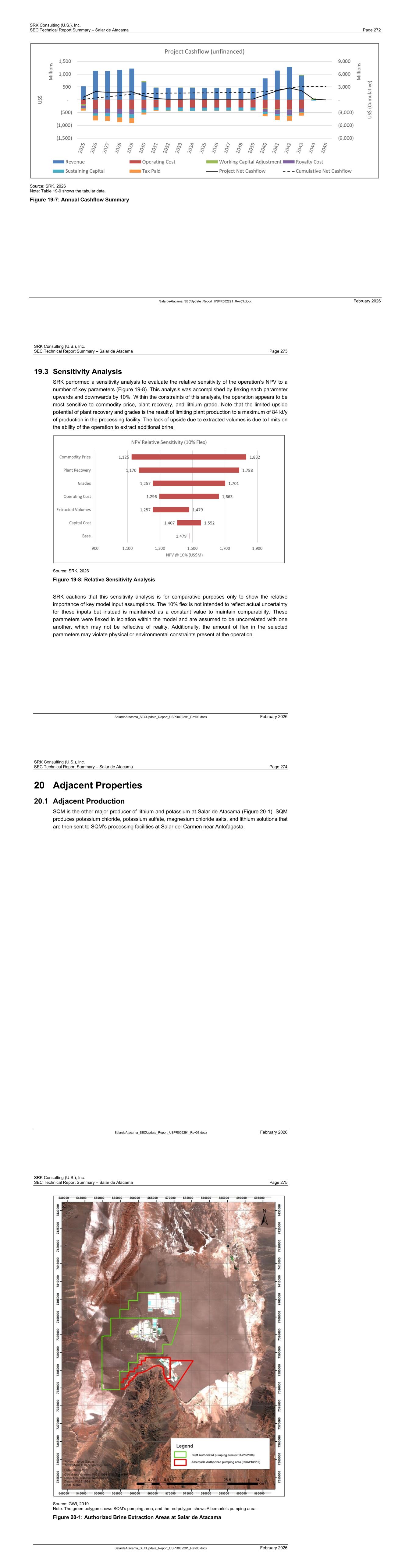

SRK Consulting (U.S.), Inc. SEC Technical Report Summary – Salar de Atacama Page xii SalardeAtacama_SECUpdate_Report_USPR002291_Rev03.docx February 2026 Figure 14-4: Lithium Brine Evaporation Stages .............................................................................................. 177 Figure 14-5: Aerial View of ALB Evaporation Ponds ...................................................................................... 178 Figure 14-6: SYIP Completed Facility ............................................................................................................ 181 Figure 14-7: La Negra Flowsheet ................................................................................................................... 183 Figure 14-8: Boron Removal Scheme by SX .................................................................................................. 185 Figure 14-9: Scheme Removal of Calcium and Magnesium by Precipitation with Calcium Oxide and Sodium Carbonate .......................................................................................................................................... 187 Figure 14-10: Method of Obtaining Li2CO3 by Precipitation with Sodium Carbonate ..................................... 189 Figure 14-11: Method of Thermal Evaporation for Lithium and Water Recovery ........................................... 190 Figure 15-1: General Project Major Facility Location ..................................................................................... 195 Figure 15-2: Angamos Port/Antofagasta Port ................................................................................................. 196 Figure 15-3: Angamos Port/Antofagasta Port ................................................................................................. 197 Figure 15-4: Regional Communities Near the Salar ....................................................................................... 199 Figure 15-5: Salar Plant Facilities ................................................................................................................... 201 Figure 15-6: La Negra Plant Facilities ............................................................................................................ 203 Figure 16-1: EV Sales and Penetration Rates (‘000 vehicles, %) .................................................................. 210 Figure 16-2: Lithium Demand in Key Sectors ('000 LCE tonnes) ................................................................... 211 Figure 16-3: Forecast Mine Supply ('000 tonnes LCE) .................................................................................. 214 Figure 16-4: Lithium Supply-Demand Balance ('000 tonnes LCE) ................................................................. 216 Figure 16-5: Lithium Battery Material Prices .................................................................................................. 217 Figure 16-6: LiOH Long-Term Forecast Scenarios (Battery Grade, Spot, CIF CJK, US$/kg, Nominal) ........ 220 Figure 16-7: Li2CO3 Long-Term Forecast Scenarios (Technical Grade, Spot, CIF CJK, US$/kg, Nominal) . 220 Figure 17-1: La Negra Water Quality Monitoring Points ................................................................................. 227 Figure 17-2: Sensitive Ecosystems in Salar de Atacama ............................................................................... 230 Figure 17-3: La Negra and Salar de Atacama Approved Financial Bonding Program .................................. 252 Figure 18-1: Total Forecast OPEX (Real 2025 Basis) ................................................................................... 258 Figure 19-1: Salar de Atacama Pumping Profile ............................................................................................ 261 Figure 19-2: Modeled Processing Profile ....................................................................................................... 263 Figure 19-3: Modeled Production Profile ........................................................................................................ 264 Figure 19-4: Life-of-Operation Operating Cost Summary .............................................................................. 266 Figure 19-5: Life-of-Operation Operating Cost Contributions ......................................................................... 267 Figure 19-6: Sustaining Capital Profile ........................................................................................................... 269 Figure 19-7: Annual Cashflow Summary ........................................................................................................ 272 Figure 19-8: Relative Sensitivity Analysis ....................................................................................................... 273 Figure 20-1: Authorized Brine Extraction Areas at Salar de Atacama ........................................................... 275 Figure 20-2: Spatial Distribution of Concessioned Water Rights in the Salar de Atacama Basin .................. 278 SRK Consulting (U.S.), Inc. SEC Technical Report Summary – Salar de Atacama Page xiii SalardeAtacama_SECUpdate_Report_USPR002291_Rev03.docx February 2026 List of Abbreviations The metric system has been used throughout this report. Tonnes are metric of 1,000 kg, or 2,204.6 lb. All currency is in U.S. dollars (US$) unless otherwise stated. Abbreviation Definition % percent < less than > greater than °C degrees Celsius µS/cm microsiemens per centimeter 2D two-dimensional 3D three-dimensional A/P accounts payable A/R accounts receivable ADI Indigenous Development Area Al aluminum Albemarle Albemarle Corporation B boron Ba barium BEV battery electric vehicle C&M care and maintenance Ca calcium CaCl2 calcium chloride CaCO3 calcium carbonate CAGR compound average growth rate CAPEX capital expenditure CASEME Carlos Sáez – Eduardo Morales Echeverría CCHEN Chilean Nuclear Energy Commission CIF cost, insurance, and freight CISL Igneous-Sedimentary Complex of the Cordón de Lila CJK China, Japan, and Korea Cl chlorine cm centimeter CMZ Minera Zaldívar CO2 carbon dioxide CO3 carbonate CoG cut-off grade CONAF National Forestry Corporation Consejo de Defensa del Estado Chilean State Defense Council COREMA Comisión Regional del Medio Ambiente CORFO the Chilean economic development agency (Corporación de Fomento de la Producción or Production Development Corporation of Chile) CPA Council of Atacameños Peoples CV coefficient of variation DGA General Water Directorate (Dirección General de Aguas) Di Lila Formation DIA Environmental Impact Declaration (Declaración de Impacto Ambiental) DLE direct lithium extraction DO dissolved oxygen DSO direct shipped ore EC electrical conductivity EIA environmental impact assessment (estudio de impacto ambiental) eMobility electrically powered vehicles EPP equivalent pumping point ESI Environmental Simulations, Inc. SRK Consulting (U.S.), Inc. SEC Technical Report Summary – Salar de Atacama Page xiv SalardeAtacama_SECUpdate_Report_USPR002291_Rev03.docx February 2026 Abbreviation Definition ESS energy storage system EV electric vehicle EWMP environmental water monitoring plan EWP early warning plan ET evapotranspiration FCAB Ferrocarril de Antofagasta a Bolivia Fe iron Fe2O3 iron(III) oxide G&A general and administrative H2SO4 sulfuric acid ha hectare Ha alluvial Hac colluvial HCl hydrochloric acid HCO3 bicarbonate HDPE high-density polyethylene HG high lithium concentration HU hydrogeological unit ICE internal combustion engine ICMM International Council on Mining and Metals ICP inductively coupled plasma ID2 inverse distance squared IDW inverse distance weighted IDW3 inverse distance weighting cubed IRR internal rate of return K potassium K permeability K-Ar potassium-argon KCl potash kg/d kilograms per day Kh horizonal hydraulic conductivity km kilometer km2 square kilometer kt thousand tonnes K-UTEC K-UTEC AG Salt Technologies kV kilovolt kVA kilovolt-ampere kW kilowatt kWh kilowatt hour L liter L/s liters per second LAN 1 La Negra 1 LAN 2 La Negra 2 LAN 3 La Negra 3 LCE lithium carbonate equivalent LG low lithium concentration Li lithium Li2CO3 lithium carbonate LIB lithium-ion battery LiCl lithium chloride LiOH lithium hydroxide LME lithium metal equivalent LoM life-of-mine m meter m/d meters per day m2 square meter SRK Consulting (U.S.), Inc. SEC Technical Report Summary – Salar de Atacama Page xv SalardeAtacama_SECUpdate_Report_USPR002291_Rev03.docx February 2026 Abbreviation Definition m3 cubic meter m3/h cubic meters per hour m3/y cubic meters per year Ma million years ago masl meters above sea level mbar millibar MBtu/h thousand British thermal units per hour MEL Minera Escondida Mg magnesium Mg(OH)2 magnesium hydroxide mg/L milligrams per liter mm millimeter mm/y millimeters per year MNT Monturaqui-Negrillar-Tilopozo MOP muriate of potash MPga Ancient Gravel Deposits MRE mineral resource estimate MsPlc Campamento Formation Mt million tonnes MVA megavolt-ampere MW megawatt Na sodium NaCl sodium chloride NDVI normalized difference vegetation index Nm3/h normal cubic meters per hour NMR nuclear magnetic resonance NN nearest neighbor NO3 nitrate NPV net present value NPV 10% net present value using a 10% discount rate Ocisl Igneous-Sedimentary Complex of the Cordón de Lila OEM Original equipment manufacturer OK ordinary kriging OMA mining concessions in Salar de Atacama owned by CORFO OMet Tiocalar Strata OMsp San Pedro Formation OPEX operational cost Oqg Quebrada Grande Formation Pecn Cerro Negro Strata PFS prefeasibility study PHEV plug-in hybrid electric vehicle Pit Tucúcaro Ignimbrite Planta Salar Albemarle's laboratories Plfet El Tambo Formation Plgm Modern Gravel Deposits PM10 particulate matter of 10 microns PM2.5 particulate matter of 2.5 microns PMB biodiversity environmental monitoring plan PPE personal protective equipment ppm parts per million Project Salar de Atacama lithium-rich brine deposit controlled by Albemarle, its associated brine concentration facilities, and La Negra lithium processing facilities owned by Albemarle psi pounds per square inch PVC polyvinyl chloride QA/QC quality assurance/quality control QP Qualified Person