respec.com TECHNICAL REPORT SUMMARY JORDAN BROMINE OPERATION REPORT RSI-3740 PREPARED BY RESPEC Company, LLC 146 East Third Street Lexington, Kentucky 40508 PREPARED FOR Albemarle Corporation 4250 Congress Street Suite 900 Charlotte, North Carolina 28209 FEBRUARY 2026 Project Number M0580.25001 Exhibit 96.5 i DATE AND SIGNATURE PAGE This report, titled Technical Report Summary: Jordan Bromine Operation, is effective as of December 31, 2025, and was prepared and signed by RESPEC Company, LLC, acting as a Qualified Person Company. Signed and dated February 5, 2026 Signed: RESPEC Company, LLC Susan B. Patton Principal Consultant, Mining & Energy On behalf of RESPEC Company, LLC ii NOTE REGARDING FORWARD-LOOKING STATEMENT Jordan Bromine Operation Technical Report Summary as of December 31, 2025 This Technical Report Summary contains forward-looking statements within the meaning of the U.S. Securities Act of 1933 and the U.S. Securities Exchange Act of 1934, that are intended to be covered by the safe harbor created by such sections. Such forward-looking statements include, without limitation, statements regarding RESPEC’s expectation for the Jordan Bromine operation, including estimated cashflows, production forecasts, mine plans, revenue, income, costs, taxes, capital, rates of return, mine, material mined and processed, recoveries and grade, future mineralization, future adjustments and sensitivities and other statements that are not historical facts. Forward-looking statements address activities, events, or developments that RESPEC expects or anticipates will or may occur in the future and are based on current expectations and assumptions. Although RESPEC believes that its expectations are based on reasonable assumptions, it can give no assurance that these expectations will prove correct. Such assumptions include, but are not limited to: (i) permitting, development, operations and expansion of operations and projects being consistent with current expectations and mine plans; (ii) political developments in jurisdiction in which Jordan Bromine operates being consistent with current expectations; (iii) certain exchange rate assumptions being approximately consistent with current levels; (iv) certain price assumptions for elemental bromine; (v) prices for key supplies being approximately consistent with current levels; and (vi) other planning assumptions. This notice is an integral component of the Technical Report Summary (TRS) and should be read in its entirety and must accompany every copy made of the TRS. RESPEC has used their experience and industry expertise to produce the estimates in the TRS. Where RESPEC has made these estimates, they are subject to qualifications and assumptions, and it should also be noted that all estimates contained in the TRS may be prone to fluctuations with time and changing industry circumstances. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS 1.0 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .................................................................................................................................................... 1 1.1 PROPERTY DESCRIPTION ....................................................................................................................................................................1 1.2 MINERAL RIGHTS ...................................................................................................................................................................................1 1.3 GEOLOGICAL SETTING, MINERALIZATION AND DEPOSIT ..........................................................................................................1 1.4 EXPLORATION ........................................................................................................................................................................................2 1.5 MINERAL PROCESSING AND METALLURGICAL TESTING ..........................................................................................................2 1.6 MINERAL RESOURCE ESTIMATES .....................................................................................................................................................2 1.7 MINERAL RESERVE ESTIMATES ........................................................................................................................................................3 1.8 MINING METHODS ................................................................................................................................................................................3 1.9 PROCESSING AND RECOVERY METHODS ......................................................................................................................................4 1.10 INFRASTRUCTURE .................................................................................................................................................................................4 1.11 MARKET STUDIES ..................................................................................................................................................................................4 1.12 ENVIRONMENTAL STUDIES, PERMITTING AND PLANS, NEGOTIATIONS, OR AGREEMENTS WITH LOCAL INDIVIDUALS OR GROUPS ..................................................................................................................................................................5 1.13 CAPITAL AND OPERATING COSTS ....................................................................................................................................................5 1.14 ECONOMIC ANALYSIS ..........................................................................................................................................................................6 1.15 INTERPRETATION AND CONCLUSIONS ..........................................................................................................................................6 1.16 RECOMMENDATIONS ...........................................................................................................................................................................6 2.0 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................................................... 7 2.1 ISSUER OF REPORT ...............................................................................................................................................................................7 2.2 TERMS OF REFERENCE AND PURPOSE ...........................................................................................................................................7 2.3 SOURCES OF INFORMATION ..............................................................................................................................................................7 2.4 GLOSSARY ...............................................................................................................................................................................................8 2.5 PERSONAL INSPECTION ......................................................................................................................................................................10 3.0 PROPERTY DESCRIPTION ............................................................................................................................................... 11 3.1 JORDAN LAND MANAGEMENT AND REGULATORY FRAMEWORK ..........................................................................................11 3.2 MINERAL RIGHTS ...................................................................................................................................................................................11 3.2.1 Jordan Bromine Company and Albemarle Joint Venture ............................................................................................11 3.2.2 Arab Potash Company ...........................................................................................................................................................15 3.3 SIGNIFICANT ENCUMBRANCES OR RISKS TO PERFORMING WORK ON PERMITS .............................................................15 4.0 ACCESSIBILITY, CLIMATE, LOCAL RESOURCES, INFRASTRUCTURE, AND PHYSIOGRAPHY ..................................... 16 4.1 TOPOGRAPHY AND VEGETATION .....................................................................................................................................................16 4.2 ACCESSIBILITY AND LOCAL RESOURCES .......................................................................................................................................20 4.3 CLIMATE ...................................................................................................................................................................................................21 4.4 INFRASTRUCTURE .................................................................................................................................................................................22

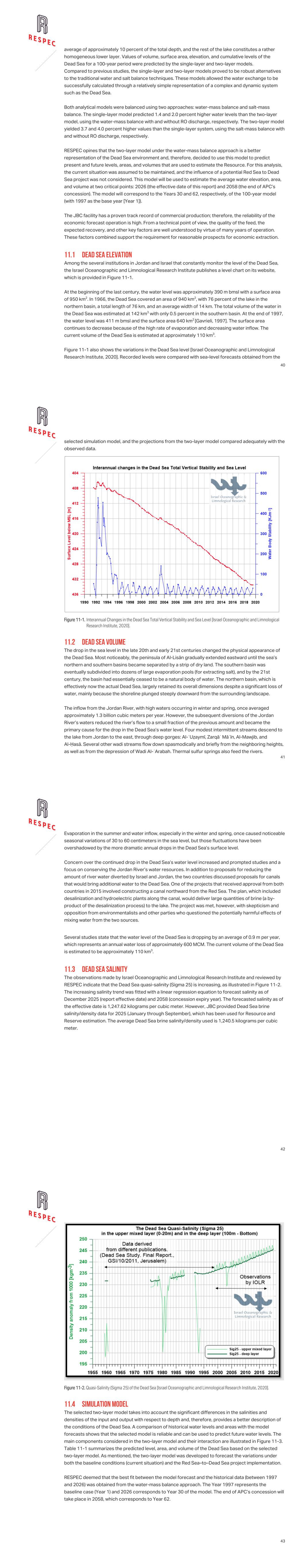

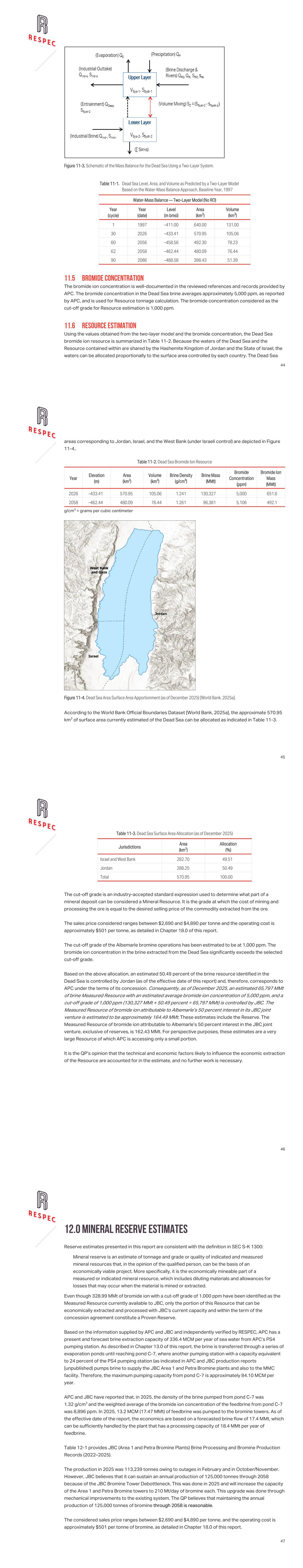

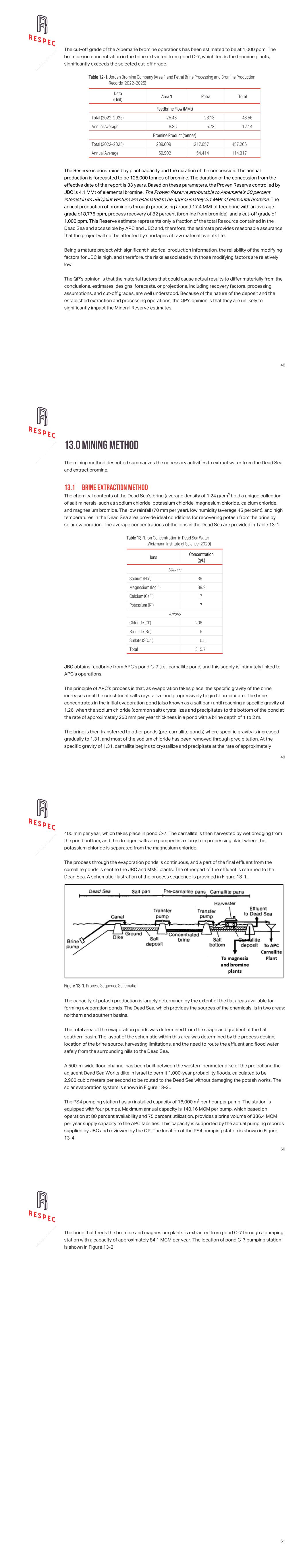

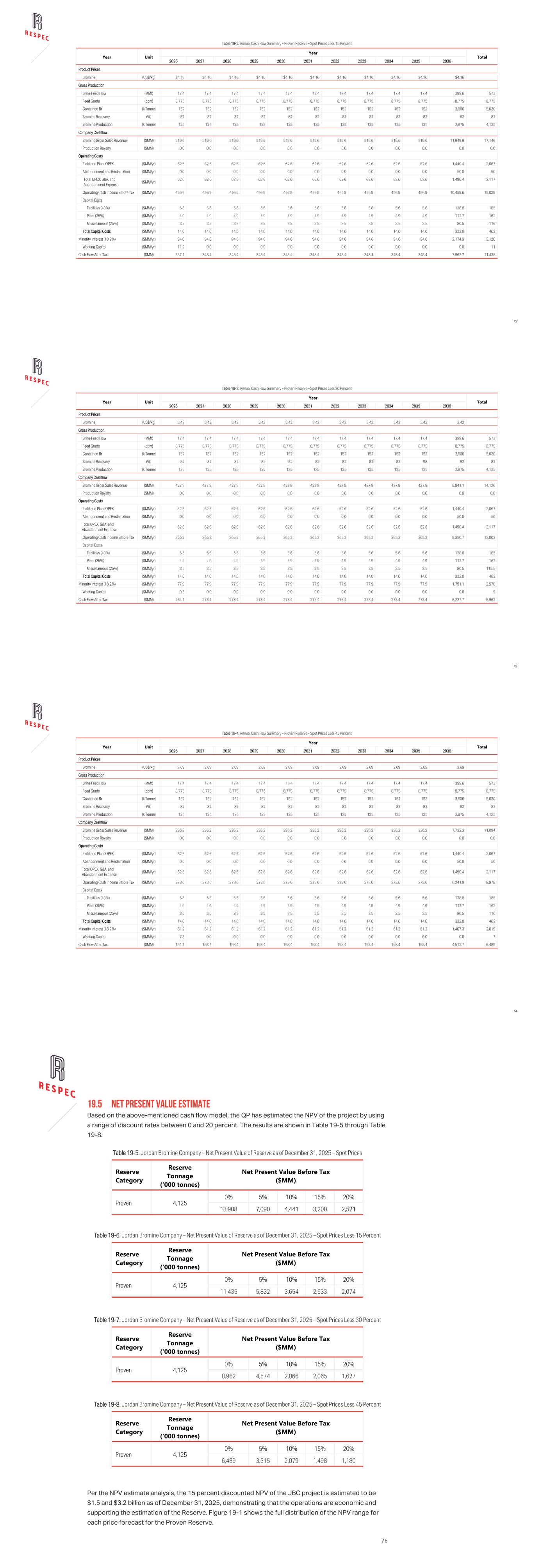

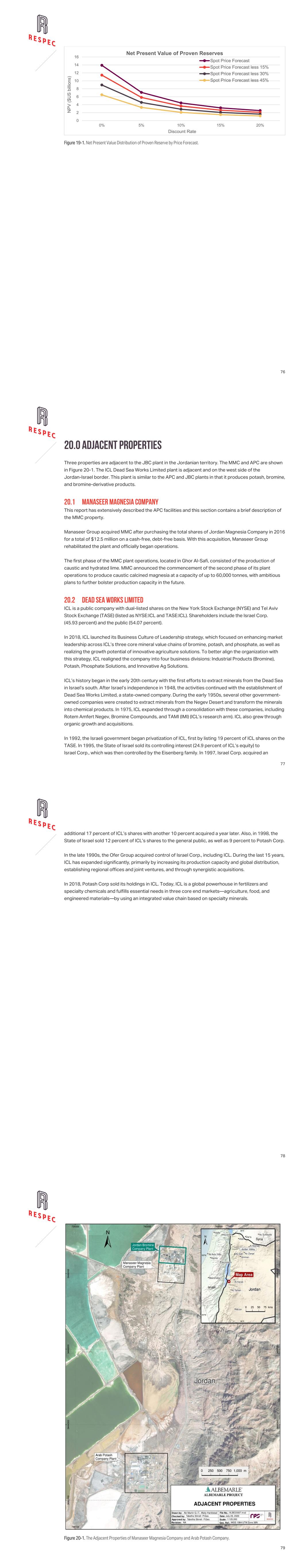

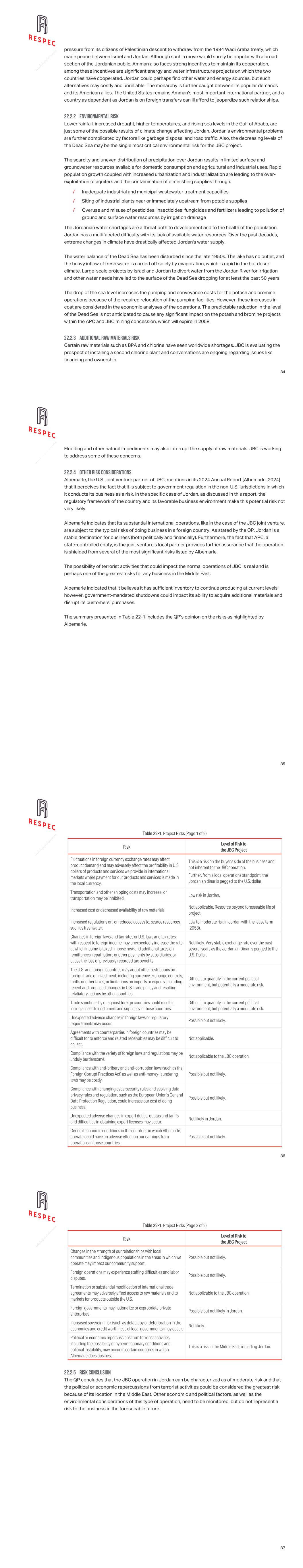

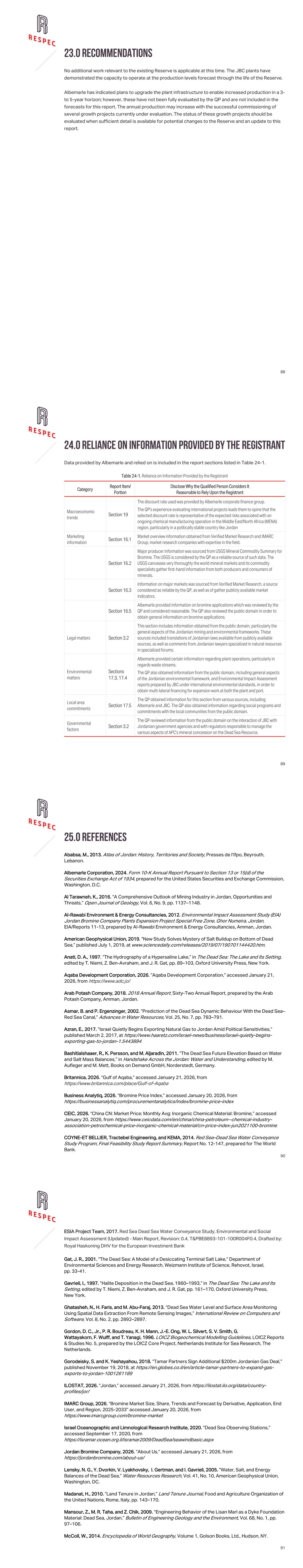

iv 4.5 WATER RESOURCES .............................................................................................................................................................................23 5.0 HISTORY ........................................................................................................................................................................... 24 6.0 GEOLOGICAL SETTING, MINERALIZATION, AND DEPOSIT ........................................................................................... 25 6.1 REGIONAL GEOLOGY ............................................................................................................................................................................25 6.2 LOCAL GEOLOGY ...................................................................................................................................................................................25 6.3 PROPERTY GEOLOGY AND MINERALIZATION ...............................................................................................................................31 7.0 EXPLORATION .................................................................................................................................................................. 33 8.0 SAMPLE PREPARATION, ANALYSES, AND SECURITY ................................................................................................... 35 9.0 DATA VERIFICATION ....................................................................................................................................................... 36 10.0 MINERAL PROCESSING AND METALLURGICAL TESTING ............................................................................................. 37 10.1 BRINE SAMPLE COLLECTION .............................................................................................................................................................37 10.2 SECURITY .................................................................................................................................................................................................38 10.3 ANALYTICAL METHOD .........................................................................................................................................................................38 11.0 MINERAL RESOURCE ESTIMATES .................................................................................................................................. 39 11.1 DEAD SEA ELEVATION ..........................................................................................................................................................................40 11.2 DEAD SEA VOLUME ...............................................................................................................................................................................41 11.3 DEAD SEA SALINITY ..............................................................................................................................................................................42 11.4 SIMULATION MODEL ............................................................................................................................................................................43 11.5 BROMIDE CONCENTRATION ..............................................................................................................................................................44 11.6 RESOURCE ESTIMATION .....................................................................................................................................................................44 12.0 MINERAL RESERVE ESTIMATES ..................................................................................................................................... 47 13.0 MINING METHOD ............................................................................................................................................................. 49 13.1 BRINE EXTRACTION METHOD ............................................................................................................................................................49 13.2 LIFE-OF-MINE PRODUCTION SCHEDULE .......................................................................................................................................55 14.0 PROCESSING AND RECOVERY METHODS ..................................................................................................................... 56 14.1 MINERAL RECOVERY PROCESS WALKTHROUGH ........................................................................................................................56 15.0 INFRASTRUCTURE ........................................................................................................................................................... 58 15.1 ROADS AND RAIL ...................................................................................................................................................................................58 15.2 PORT FACILITIES ....................................................................................................................................................................................58 15.3 PLANT FACILITIES..................................................................................................................................................................................60 15.3.1 Water Supply ............................................................................................................................................................................60 15.3.2 Power Supply ...........................................................................................................................................................................60 15.3.3 Brine Supply .............................................................................................................................................................................60 15.3.4 Waste-Steam Management .................................................................................................................................................60 16.0 MARKET STUDIES ............................................................................................................................................................ 61 16.1 BROMINE MARKET OVERVIEW...........................................................................................................................................................61 16.2 MAJOR PRODUCERS ............................................................................................................................................................................61 v 16.3 MAJOR MARKETS ..................................................................................................................................................................................62 16.4 BROMINE PRICE TREND .......................................................................................................................................................................62 16.5 BROMINE APPLICATIONS ....................................................................................................................................................................63 17.0 ENVIRONMENTAL STUDIES, PERMITTING AND PLANS, NEGOTIATIONS, OR AGREEMENTS WITH LOCAL INDIVIDUALS OR GROUPS ....................................................................................................................................................... 64 17.1 ENVIRONMENTAL STUDIES ................................................................................................................................................................64 17.2 ENVIRONMENTAL COMPLIANCE ......................................................................................................................................................64 17.2.1 Compliance With National Standards ...............................................................................................................................64 17.2.2 Compliance With International Standards .......................................................................................................................64 17.2.3 Environmental Monitoring ...................................................................................................................................................65 17.3 REQUIREMENTS AND PLANS FOR WASTE AND TAILINGS DISPOSAL ....................................................................................65 17.4 PROJECT PERMITTING REQUIREMENTS ........................................................................................................................................65 17.5 QUALIFIED PERSON'S OPINION .........................................................................................................................................................66 18.0 CAPITAL AND OPERATING COSTS .................................................................................................................................. 67 18.1 CAPITAL COSTS .....................................................................................................................................................................................67 18.1.1 Development Facilities Costs ..............................................................................................................................................67 18.1.2 Plant Maintenance Capital (Working Capital) .................................................................................................................67 18.2 OPERATING COSTS ...............................................................................................................................................................................67 19.0 ECONOMIC ANALYSIS ..................................................................................................................................................... 69 19.1 ROYALTIES...............................................................................................................................................................................................69 19.2 BROMINE MARKET AND SALES .........................................................................................................................................................69 19.3 INCOME TAX ............................................................................................................................................................................................69 19.4 CASH FLOW RESULTS ..........................................................................................................................................................................70 19.5 NET PRESENT VALUE ESTIMATE .......................................................................................................................................................75 20.0 ADJACENT PROPERTIES ................................................................................................................................................. 77 20.1 MANASEER MAGNESIA COMPANY ...................................................................................................................................................77 20.2 DEAD SEA WORKS LIMITED ................................................................................................................................................................77 21.0 OTHER RELEVANT DATA AND INFORMATION ............................................................................................................... 80 22.0 INTERPRETATION AND CONCLUSIONS ......................................................................................................................... 81 22.1 GENERAL ..................................................................................................................................................................................................81 22.2 DISCUSSION OF RISK ...........................................................................................................................................................................82 22.2.1 Geopolitical Risk .....................................................................................................................................................................83 22.2.2 Environmental Risk.................................................................................................................................................................84 22.2.3 Additional Raw Materials Risk .............................................................................................................................................84 22.2.4 Other Risk Considerations ....................................................................................................................................................85 22.2.5 Risk Conclusion .......................................................................................................................................................................87 23.0 RECOMMENDATIONS ...................................................................................................................................................... 88 24.0 RELIANCE ON INFORMATION PROVIDED BY THE REGISTRANT ................................................................................... 89 vi 25.0 REFERENCES .................................................................................................................................................................... 90 vii LIST OF TABLES Table Page 2-1 Glossary of Terms ............................................................................................................................................................................................ 8 6-1 Typical Concentration of Ions in the Dead Sea and Regular Sea Water Grams per Liter ............................................................. 32 11-1 Dead Sea Level, Area, and Volume as Predicted by a Two-Layer Model Based on the Water-Mass Balance Approach, Baseline Year, 1997 ................................................................................................................................................................... 44 11-2 Dead Sea Bromide Ion Resource ................................................................................................................................................................. 45 11-3 Dead Sea Surface Area Allocation (as of December 2025) .................................................................................................................. 46 12-1 Jordan Bromine Company (Area 1 and Petra) Brine Processing and Bromine Production Records (2022–2025) .............. 48 13-1 Ion Concentration in Dead Sea Water ........................................................................................................................................................ 49 13-2 Life-of-Mine Production Schedule ............................................................................................................................................................. 55 15-1 Materials Stored at Aqaba Port .................................................................................................................................................................... 58 15-2 Materials Stored at Jordan Bromine Company Terminal...................................................................................................................... 59 16-1 Bromine Production by Leading Countries (2020–2024) .................................................................................................................... 61 18-1 Summary of Operating and Capital Expenditures .................................................................................................................................. 68 19-1 Annual Cash Flow Summary – Proven Reserve – Spot Prices............................................................................................................... 71 19-2 Annual Cash Flow Summary – Proven Reserve – Spot Prices Less 15 Percent ............................................................................... 72 19-3 Annual Cash Flow Summary – Proven Reserve – Spot Prices Less 30 Percent ............................................................................... 73 19-4 Annual Cash Flow Summary – Proven Reserve – Spot Prices Less 45 Percent ............................................................................... 74 19-5. Jordan Bromine Company – Net Present Value of Reserve as of December 31, 2025 – Spot Prices ........................................ 75 19-6 Jordan Bromine Company – Net Present Value of Reserve as of December 31, 2025 – Spot Prices Less 15 Percent ............................................................................................................................................................................................................... 75 19-7 Jordan Bromine Company – Net Present Value of Reserve as of December 31, 2025 – Spot Prices Less 30 Percent ............................................................................................................................................................................................................... 75 19-8 Jordan Bromine Company – Net Present Value of Reserve as of December 31, 2025 – Spot Prices Less 45 Percent ............................................................................................................................................................................................................... 75 22-1 Project Risks ..................................................................................................................................................................................................... 86 24-1 Reliance on Information Provided by the Registrant ............................................................................................................................. 89

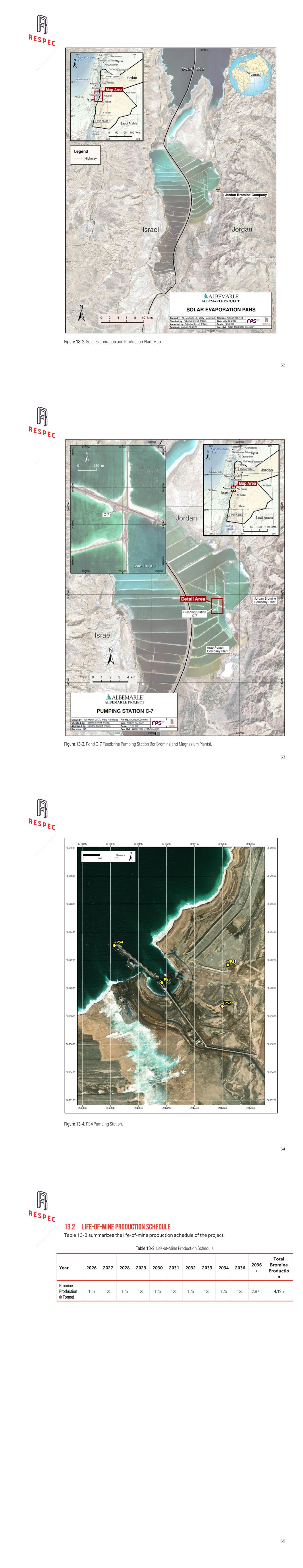

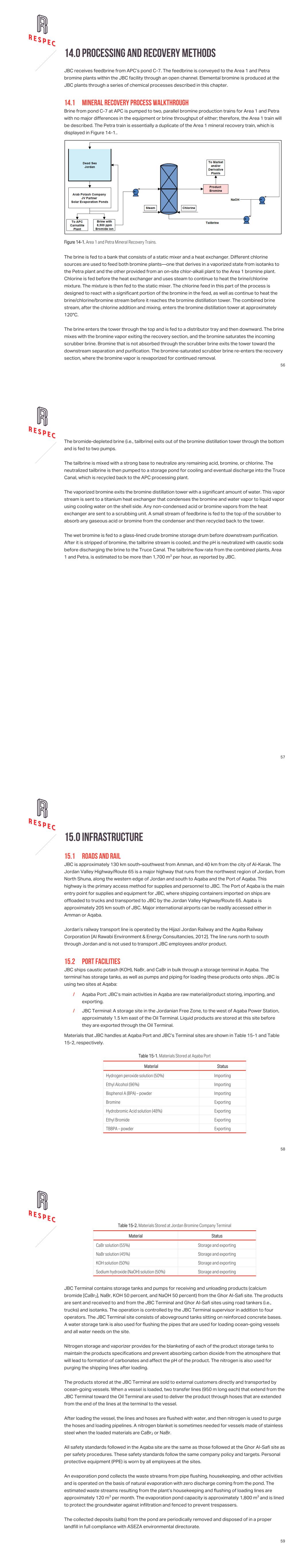

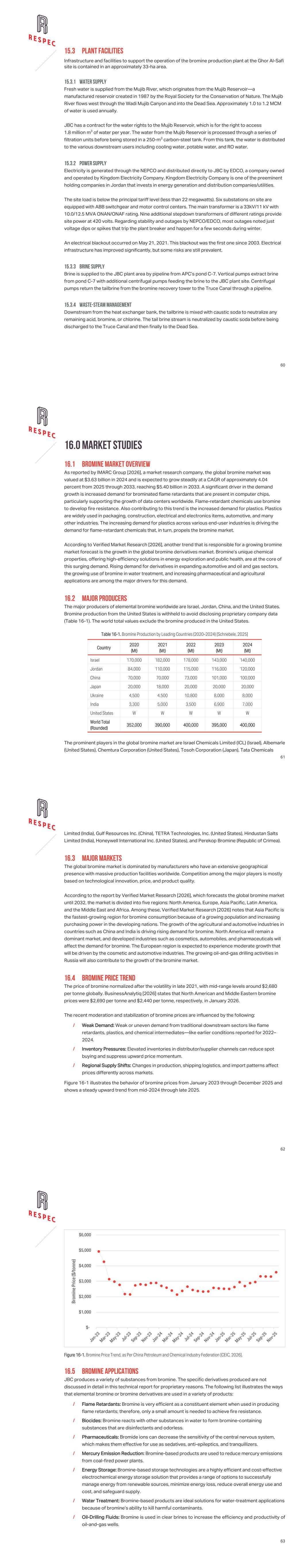

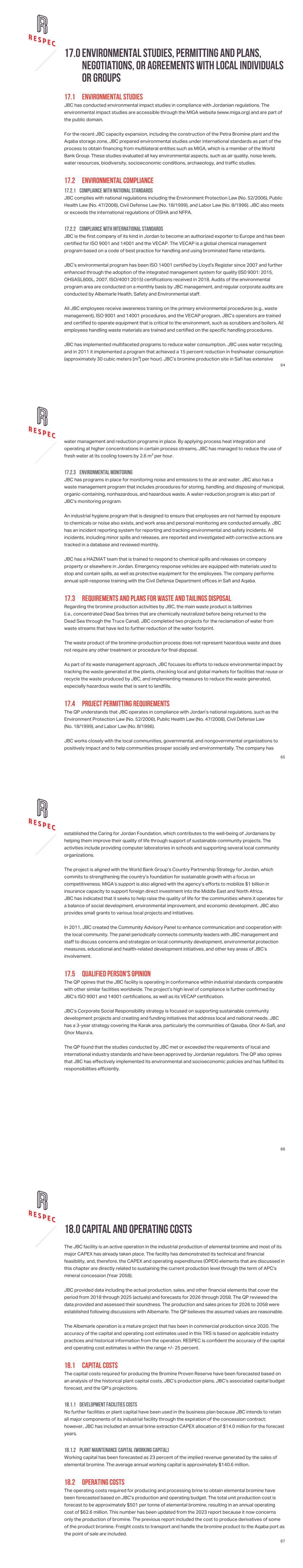

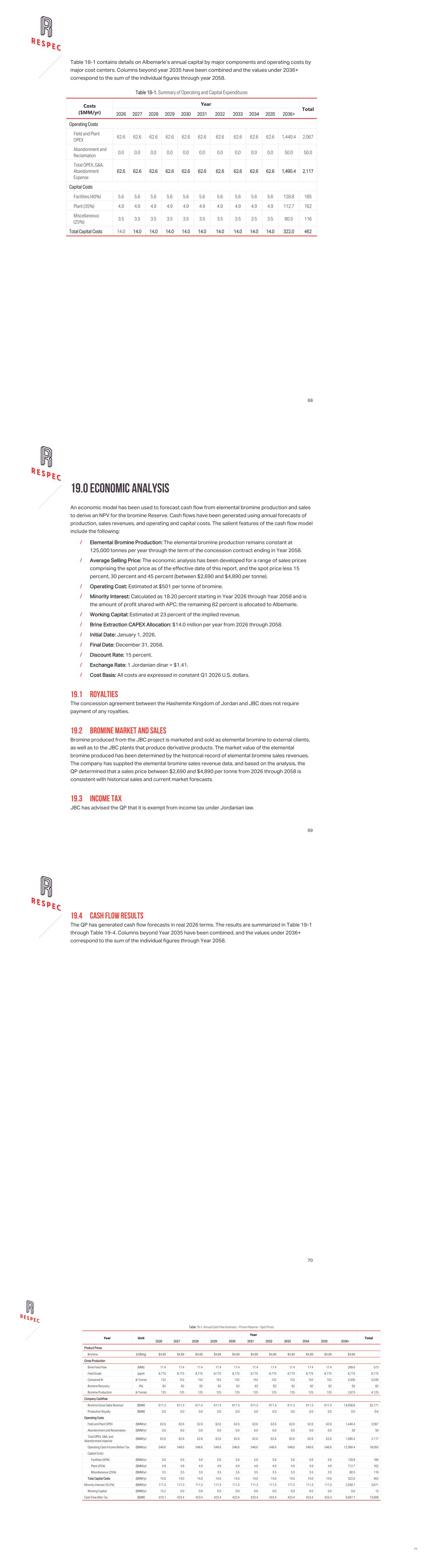

viii LIST OF FIGURES FIGURE Page 3-1 Jordan Bromine Company Project Location Map................................................................................................................................... 13 3-2 Administrative Divisions of Jordan ............................................................................................................................................................. 14 4-1 Morphological Features and General Elevation ...................................................................................................................................... 18 4-2 Vegetation Types of Jordan.......................................................................................................................................................................... 19 4-3 Average Annual Rainfall ................................................................................................................................................................................. 22 6-1 Physiological Features ................................................................................................................................................................................... 26 6-2 (A) Plan View of the Dead Sea in Relation to the Western Boundary Fault and the Arava Fault and (B) Generalized Cross Section of the Dead Sea Lake Geology .......................................................................................................................................... 27 6-3 Main Regional Faults in the Area ................................................................................................................................................................. 27 6-4 Map of the Jordan Bromine Company Area and Its Generalized Geology, Including Faults ....................................................... 28 6-5 Depositional Settings of the Dead Sea ...................................................................................................................................................... 29 11-1 Interannual Changes in the Dead Sea Total Vertical Stability and Sea Level .................................................................................. 41 11-2 Quasi-Salinity (Sigma 25) of the Dead Sea ............................................................................................................................................... 43 11-3 Schematic of the Mass Balance for the Dead Sea Using a Two-Layer System ............................................................................... 44 11-4 Dead Sea Area Surface Area Apportionment (as of December 2025)............................................................................................... 45 13-1 Process Sequence Schematic ..................................................................................................................................................................... 50 13-2 Solar Evaporation and Production Plant Map .......................................................................................................................................... 52 13-3 Pond C-7 Feedbrine Pumping Station (for Bromine and Magnesium Plants) ................................................................................. 53 13-4 PS4 Pumping Station ..................................................................................................................................................................................... 54 14-1 Area 1 and Petra Mineral Recovery Trains ................................................................................................................................................ 56 16-1 Bromine Price Trend, as Per China Petroleum and Chemical Industry Federation ........................................................................ 63 19-1 Net Present Value Distribution of Proven Reserve by Price Forecast ................................................................................................ 76 20-1 The Adjacent Properties of Manaseer Magnesia Company and Arab Potash Company .............................................................. 79 1 1.0 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY This Technical Report Summary (TRS) was prepared by RESPEC Company, LLC (RESPEC) at the request of Albemarle Corporation (Albemarle, or the company) for the company’s Jordan Bromine Company (JBC) to update a previously filed TRS to reflect depletion by extraction and increased plant capacity. The TRS complies with disclosure standards of the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission’s S-K Regulation 1300 (SEC S-K 1300), following the TRS outline described in Code of Federal Regulations (CFR) 17, and reports the estimated Reserve for the Jordan bromine operation, as well as all summary information required as outlined in SEC S-K 1300. 1.1 PROPERTY DESCRIPTION The JBC operation is located in Safi in the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan (Jordan) and is located on a 33-hectare (ha) area on the southeastern edge of the Dead Sea, which is approximately 6 kilometers (km) north of the Arab Potash Company (APC) plant. JBC also has a 2-ha storage facility within the Jordanian Free Zone at the Port of Aqaba. 1.2 MINERAL RIGHTS JBC was established in 1999 and is a joint venture between Albemarle Holdings Company Limited, a wholly owned subsidiary of Albemarle, and APC. JBC’s operations primarily consist of the manufacturing of bromine from bromide-enriched brine, which is a by-product of potash operations conducted by APC. The Government of the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan granted APC a concession for exclusive rights to exploit the minerals and salts from the Dead Sea brine until 2058. Rights granted to APC apply to JBC by virtue of APC’s participation in the joint venture. APC maintains all the necessary permits to guarantee the continuous operation of its facilities under Jordanian legislation. 1.3 GEOLOGICAL SETTING, MINERALIZATION AND DEPOSIT The movement of the plates that created the basin containing the Dead Sea began 15 million years ago (Ma), and the plates continue to diverge today at a rate of 5 to 10 millimeters (mm) per year [Warren, 2006]. The Dead Sea is an isolated hypersaline lake within the lowest part of the catchment basin; it is a unique, current-day example of evaporitic sedimentation and accumulation within a brine body [Warren, 2006]. The climate, geology, and location provide a setting that makes the Dead Sea a valuable large-scale natural resource for potash and bromine. As of the effective date, the Dead Sea has a surface area of 571 square kilometers (km2) and a brine volume of 105 cubic kilometers (km3). The Dead Sea is the world’s saltiest natural lake [Wisniak, 2002], containing high concentrations of ions compared to that of regular seawater and an unusually high amount of magnesium and bromine. Evaporation greatly exceeds the inflow of water to the Dead Sea, causing a negative water balance and a shoreline recession of approximately 1.1 meters (m) to 1.25 m per year [Warren, 2006]. Variable evaporation rates and uncertain subsurface inflow of fresh water make it difficult to predict its water 2 deficit. The Dead Sea contains a large and deep northern basin and a shallow southern basin. The southern basin is a saline mudflat, and the water level is maintained by artificial flooding with northern basin brine. 1.4 EXPLORATION Although typically conducted, no exploration was required to characterize the mineral deposit because the minerals are extracted from the Dead Sea, which has been extensively characterized. A limited site investigation program was conducted in 1966, when most of the southern basin of the Dead Sea was covered in up to 3 m of brine. A more detailed program, with a cost of £3 million, took place in 1977 when the brine level had receded from the southern basin, leaving only land-locked ponds in the central depression. 1.5 MINERAL PROCESSING AND METALLURGICAL TESTING The JBC bromine plants and connection to the APC carnallite pond C-7 were designed to move substantial quantities of concentrated brine to the central bromine production facilities, where brine is processed into bromine. Knowing the consistency of bromide salts (bromides) in the bromide-enriched brine (feedbrine) is critical for operations and business planning for bromine derivative sales. Feedbrine and heated bromide-depleted brine (tailbrine) samples are collected frequently upstream and downstream of the bromine tower to capture any concentration changes. The sampling process is systematic and documented. A widely used halogen titration process is used to measure bromide in brine; the methods appear to be reasonable and well established. The sampling and analytical processes are adequate to support the plant operation. 1.6 MINERAL RESOURCE ESTIMATES JBC’s bromine production plant is atypical of many mineral processing operations in that the feedstock for the plant is concentrated brine available from another mineral processing plant owned by APC. The feedstock for the APC plant is sourced from the Dead Sea, a nonconventional reservoir shared by Israel and Jordan. As such, there is no specific Resource owned by APC or JBC; rather, APC has exclusive rights granted by the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan to withdraw brine from the Dead Sea and process it to extract minerals. The Measured Resource of bromide ion attributable to Albemarle’s 50 percent interest in its JBC joint venture, inclusive of Reserve, is estimated to be approximately 164.49 million metric tonnes (MMt). The Measured Resource of bromide ion attributable to Albemarle’s 50 percent interest in the JBC joint venture, exclusive of reserves, is 162.43 MMt. From these large Resources, JBC is extracting approximately 1 percent of the bromine available. 3 1.7 MINERAL RESERVE ESTIMATES Proven and Probable Reserves have been estimated based on the operational parameters, economics, and concession agreement held by JBC. The Reserve estimate is constrained by the time available under the concession agreement with the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan, and the processing capability of the plant. The forecast volumes of brine processed are supported by demonstrated plant performance. The Reserve estimate is not constrained by the available Resource, with approximately 1 percent of the Measured Resource being consumed. Costs are based on forward projections supported by historical operating and capital costs, with no major capital projects or plant expansions required to support the operating forecast. Revenues are based on a range of bromine sales prices between the spot price for the effective date of December 31, 2025, and the spot price less 15 percent, 30 percent, and 45 percent. The plants are forecast to process approximately 17.4 MMt of feedbrine per year on average over the remaining concession life. On an annual basis, the feed contains approximately 152,000 tonnes of bromide ion. At the plant processing recovery of 82 percent (bromine from bromide), product bromine is estimated at approximately 125,000 tonnes per year. The APC concession and JBC’s ownership of the facility expire at the end of 2058. Over the 33 years of production from the Reserve effective date of December 31, 2025, an estimated 4.1 MMt of bromine will be produced, which establishes the Reserve estimate. The Proven Reserve attributable to Albemarle’s 50 percent interest in its JBC joint venture is estimated to be approximately 2.1 MMt of elemental bromine. 1.8 MINING METHODS Mining methods consist of all activities necessary to extract brine from the Dead Sea and extract bromine. The low rainfall, low humidity, and high temperatures in the Dead Sea area provide ideal conditions for recovering potash from the brine by solar evaporation. JBC obtains its feedbrine from APC’s evaporation carnallite pond C-7, and this supply is closely linked to the APC operation. As evaporation occurs, the specific gravity of the brine increases until its constituent salts progressively crystallize and precipitate out of solution, starting with sodium chloride (common salt), which precipitates out to the bottom of the ponds (pre-carnallite ponds). Brine is transferred to other ponds in succession, where its specific gravity increases further, ultimately precipitating out all of the sodium chloride. Carnallite precipitation takes place at the carnallite pond C-7, where it is harvested from the brine and pumped as slurry to a process plant (where the potassium chloride is separated from the magnesium chloride). JBC extracts the bromide-rich, carnallite-free brine from pond C-7 through a pumping station with a capacity of approximately 84.1 million cubic meters (MCM) per year. This brine feeds the bromine and magnesium plants.

4 1.9 PROCESSING AND RECOVERY METHODS Feedbrine is conveyed to the two bromine plants via two parallel bromine production trains within the JBC facility via an open channel. Elemental bromine is produced at the JBC plants through a series of chemical processes. The brine is mixed with chlorine to extract the bromine from the solution. Chlorinated brine enters the bromine distillation tower (at approximately 120 degrees Celsius [°C]). Chlorine is added to continue the reaction with any residual bromides, and the brine stream is heated by adding steam, maintaining a temperature above the boiling point. Bromine exiting the recovery section of the tower is purified. Tailbrine exits the bromine distillation tower and is mixed with a strong base to neutralize any remaining acid, bromine, or chlorine. The tailbrine is then pumped to a storage pond for cooling and eventual discharge, and recycled back to the Dead Sea via the APC process plant. Vaporized bromine is condensed, and the wet bromine is fed to a glass-lined crude bromine storage drum that acts as an intermediate storage before downstream purification (and removal of any dissolved chlorine). 1.10 INFRASTRUCTURE The Jordan Valley Highway/Route 65 is the primary method of access for supplies and personnel to JBC. The Port of Aqaba is the main entry point for supplies and equipment for JBC, where imported shipping containers are offloaded from ships and are transported by truck to JBC via the Jordan Valley Highway. Aqaba is approximately 205 km south of JBC via Highway/Route 65. Major international airports can be readily accessed either in Amman or Aqaba. Jordan’s railway transport runs north to south through Jordan and is not used to transport JBC employees and products. JBC ships products in bulk through a storage terminal in Aqaba. The terminal has aboveground storage tanks, as well as pumps and piping for loading products onto ships. JBC’s main activities in Aqaba are raw material/product storing, importing, and exporting. An evaporation pond collects the waste streams from pipe flushing, housekeeping, and other activities. Infrastructure and facilities to support the operation of the bromine production plant at the Safi site is compact and contained in an approximately 33-ha area. Fresh water is sourced from the Mujib Reservoir, a manufactured reservoir. Approximately 1.0 to 1.2 MCM of water is used annually. Electricity is generated by the National Electric Power Company of Jordan (NEPCO) and distributed directly to JBC via the Electricity Distribution Company (EDCO), which is owned and operated by Kingdom Electricity Company. Overall, the project is well supported by quality infrastructure. 1.11 MARKET STUDIES The global bromine market is expected to grow steadily at a Compound Annual Growth Rate (CAGR) of approximately 4.04 percent between 2025 and 2033. A significant driver in the demand growth is increased demand for brominated flame retardants that are present in computer chips, particularly supporting the growth of data centers worldwide. Flame-retardant chemicals use bromine to develop 5 fire resistance. Also contributing to this trend is the increased demand for plastics. Plastics are widely used in packaging, construction, electrical and electronics items, automotive, and many other industries. The increasing demand for plastics across various end-user industries is driving the demand for flame-retardant chemicals that, in turn, propels the bromine market. The major producers of elemental bromine worldwide are Israel, Jordan, China, and the United States. The global bromine market is dominated by manufacturers who have an extensive geographical presence with production facilities worldwide. A forecast of the global bromine market through 2032 suggests that Asia would be the fastest-growing region for bromine consumption because of a growing population and the increasing purchasing power in the developing nations. The growth of the agricultural and automotive industries in countries such as China and India will also drive rising demand for bromine. The price of bromine normalized after the volatility in late 2021, with mid-range levels around $2,680 per tonne globally. The North American and Middle Eastern bromine prices were $2,690 per tonne and $2,440 per tonne, respectively, in January 2026. 1.12 ENVIRONMENTAL STUDIES, PERMITTING AND PLANS, NEGOTIATIONS, OR AGREEMENTS WITH LOCAL INDIVIDUALS OR GROUPS JBC has carried out environmental impact studies in compliance with Jordanian regulations. The environmental impact studies are available on the Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency (MIGA) website (www.miga.org) and are in the public domain. JBC complies with national environmental and labor regulations. It also meets or exceeds the international regulations of the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) and (National Fire Protection Association (NFPA). JBC is the first company of its kind in Jordan to become an authorized exporter into Europe and has been certified for International Organization of Standards (ISO) 9001 and 14001 and the Voluntary Emissions Control Action Program (VECAP). The company’s environmental program has been ISO 14001 certified by Lloyd’s Register since 2007 and further enhanced through the adoption of the integrated management system for quality (IS0 9001: 2015, OHSASL800L, 2007, ISO/4001:2015) certificate received in 2018. JBC works closely with the local communities, governmental, and nongovernmental organizations to make a positive difference and help communities prosper, both socially and environmentally. The company has established the Caring for Jordan Foundation, which contributes to the well-being of Jordanians by helping them improve their quality of life through support of sustainable community projects. 1.13 CAPITAL AND OPERATING COSTS The JBC facility is an active operation with a track record of industrial production of elemental bromine and most of the major capital expenditures (CAPEX) have already taken place. Review of the business plan provided by JBC confirmed that no further facilities or plant capital is required because JBC 6 intends to keep all the major components of its industrial facility through the expiration of the concession contract. An annual sustaining capital allocation of $14.0 million has been included. Plant operating costs and forecast budget were reviewed. Plant operating costs are expected to remain relatively constant at $501 per tonne of product bromine. 1.14 ECONOMIC ANALYSIS An economic model has been used to forecast cash flow from elemental bromine production and sales to derive a Net Present Value (NPV) for the bromine Reserve. Cash flows have been generated using annual forecasts of production, sales revenues, operating costs, and capital costs. At the assumed bromine sales price range of $2,690 to $4,890 per tonne, the operations generate an NPV of $1.5 billion to $3.2 billion at a 15 percent discount rate as of December 31, 2025, demonstrating economic viability. 1.15 INTERPRETATION AND CONCLUSIONS JBC’s primary raw material is bromide-enriched brine from the adjacent APC potash processing business. APC has mineral rights to brine extracted from the Dead Sea through 2058. The Measured Resources for bromide ion in the Dead Sea is far in excess of the stated JBC Proven Reserve of 4.1 million tonnes of elemental bromine (Albemarle’s attributable 50 percent interest of approximately 2.1 MMt). The operation has been in production since 2000 and has a demonstrated production capacity to support the Reserve estimate. 1.16 RECOMMENDATIONS No additional work relevant to the existing Reserve is applicable at this time. The JBC plants have demonstrated the capacity to operate at the production levels forecast through the life of the Reserve. Albemarle conducted major mechanical improvements to the JBC bromine towers in 2025, which will increase annual production to 125,000 tonnes during the forecast years. 7 2.0 INTRODUCTION 2.1 ISSUER OF REPORT This TRS was prepared at the request of Albemarle and is being filed under the SEC S-K 1300 reporting requirements for Albemarle’s JBC operation located in Safi, Jordan. This TRS updates a previously filed TRS, dated 24 January 2025, prepared by RPS and RESPEC to account for depletion through extraction and increased plant capacity. The purpose of the report is to support the disclosure of Mineral Resource and Mineral Reserve estimates for the Jordan Bromine property as of December 31, 2025. 2.2 TERMS OF REFERENCE AND PURPOSE The following general information applies to this TRS: / This document reports the estimated Reserve for the JBC operation, as well as all summary information required by the SEC S-K 1300. The focus of this TRS and the scientific and technical information in this report only apply to the JBC operation. RESPEC is entirely independent of Albemarle and has no interest in the mineral property discussed in this report. / This TRS was prepared by RESPEC, complies with disclosure standards of SEC S-K 1300, and follows the TRS outline described in CFR 17, Part 229.600. / The effective date of this report is December 31, 2025, which is also the deadline for the data included within this report. / Reserve estimates are presented on a 100 percent basis. The Reserve is the total Reserve for JBC; Albemarle’s share per the joint venture with APC is 50 percent. / Units presented are metric units, unless otherwise noted, and currency is expressed in United States dollars ($) unless otherwise noted. / Copyright of all text and other matters in this document, including the manner of presentation, is the exclusive property of RESPEC and Albemarle as per the Agreement signed between RESPEC and Albemarle. / RESPEC will receive a fee for preparing this TRS according to normal professional consulting practices. The fee is not contingent on the conclusions of this report and RESPEC will not receive any other benefit for preparing this report. RESPEC does not have any monetary or other interests that could be reasonably considered as capable of affecting its ability to provide an unbiased opinion in relation to the project. RESPEC is a 100 percent employee-owned global leader in integrated technology solutions for mining, energy, water, natural resources, and infrastructure. 2.3 SOURCES OF INFORMATION The interpretations and conclusions presented in this report are primarily based on the information obtained from the public sources and information provided by Albemarle. All source materials have been properly cited and referenced in Chapter 25.0 of this report.

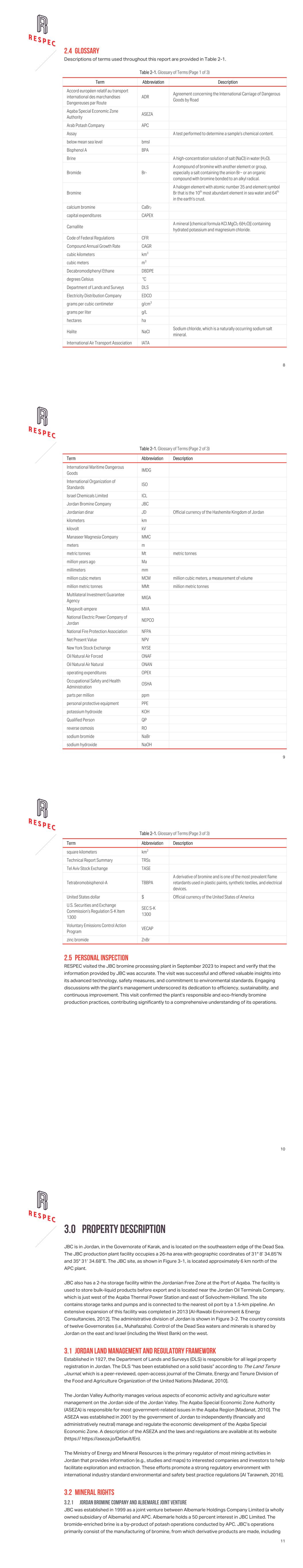

8 2.4 GLOSSARY Descriptions of terms used throughout this report are provided in Table 2-1. Table 2-1. Glossary of Terms (Page 1 of 3) Term Abbreviation Description Accord européen relatif au transport international des marchandises Dangereuses par Route ADR Agreement concerning the International Carriage of Dangerous Goods by Road Aqaba Special Economic Zone Authority ASEZA Arab Potash Company APC Assay A test performed to determine a sample’s chemical content. below mean sea level bmsl Bisphenol A BPA Brine A high-concentration solution of salt (NaCl) in water (H2O). Bromide Br- A compound of bromine with another element or group, especially a salt containing the anion Br− or an organic compound with bromine bonded to an alkyl radical. Bromine A halogen element with atomic number 35 and element symbol Br that is the 10th most abundant element in sea water and 64th in the earth’s crust. calcium bromine CaBr2 capital expenditures CAPEX Carnallite A mineral [chemical formula KCl.MgCl2 6(H2O)] containing hydrated potassium and magnesium chloride. Code of Federal Regulations CFR Compound Annual Growth Rate CAGR cubic kilometers km3 cubic meters m3 Decabromodiphenyl Ethane DBDPE degrees Celsius °C Department of Lands and Surveys DLS Electricity Distribution Company EDCO grams per cubic centimeter g/cm3 grams per liter g/L hectares ha Halite NaCl Sodium chloride, which is a naturally occurring sodium salt mineral. International Air Transport Association IATA 9 Table 2-1. Glossary of Terms (Page 2 of 3) Term Abbreviation Description International Maritime Dangerous Goods IMDG International Organization of Standards ISO Israel Chemicals Limited ICL Jordan Bromine Company JBC Jordanian dinar JD Official currency of the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan kilometers km kilovolt kV Manaseer Magnesia Company MMC meters m metric tonnes Mt metric tonnes million years ago Ma millimeters mm million cubic meters MCM million cubic meters, a measurement of volume million metric tonnes MMt million metric tonnes Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency MIGA Megavolt-ampere MVA National Electric Power Company of Jordan NEPCO National Fire Protection Association NFPA Net Present Value NPV New York Stock Exchange NYSE Oil Natural Air Forced ONAF Oil Natural Air Natural ONAN operating expenditures OPEX Occupational Safety and Health Administration OSHA parts per million ppm personal protective equipment PPE potassium hydroxide KOH Qualified Person QP reverse osmosis RO sodium bromide NaBr sodium hydroxide NaOH 10 Table 2-1. Glossary of Terms (Page 3 of 3) Term Abbreviation Description square kilometers km2 Technical Report Summary TRSs Tel Aviv Stock Exchange TASE Tetrabromobisphenol-A TBBPA A derivative of bromine and is one of the most prevalent flame retardants used in plastic paints, synthetic textiles, and electrical devices. United States dollar $ Official currency of the United States of America U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission’s Regulation S-K Item 1300 SEC S-K 1300 Voluntary Emissions Control Action Program VECAP zinc bromide ZnBr 2.5 PERSONAL INSPECTION RESPEC visited the JBC bromine processing plant in September 2023 to inspect and verify that the information provided by JBC was accurate. The visit was successful and offered valuable insights into its advanced technology, safety measures, and commitment to environmental standards. Engaging discussions with the plant’s management underscored its dedication to efficiency, sustainability, and continuous improvement. This visit confirmed the plant’s responsible and eco-friendly bromine production practices, contributing significantly to a comprehensive understanding of its operations. 11 3.0 PROPERTY DESCRIPTION JBC is in Jordan, in the Governorate of Karak, and is located on the southeastern edge of the Dead Sea. The JBC production plant facility occupies a 26-ha area with geographic coordinates of 31° 8’ 34.85”N and 35° 31’ 34.68”E. The JBC site, as shown in Figure 3-1, is located approximately 6 km north of the APC plant. JBC also has a 2-ha storage facility within the Jordanian Free Zone at the Port of Aqaba. The facility is used to store bulk-liquid products before export and is located near the Jordan Oil Terminals Company, which is just west of the Aqaba Thermal Power Station and east of Solvochem-Holland. The site contains storage tanks and pumps and is connected to the nearest oil port by a 1.5-km pipeline. An extensive expansion of this facility was completed in 2013 [Al-Rawabi Environment & Energy Consultancies, 2012]. The administrative division of Jordan is shown in Figure 3-2. The country consists of twelve Governorates (i.e., Muhafazahs). Control of the Dead Sea waters and minerals is shared by Jordan on the east and Israel (including the West Bank) on the west. 3.1 JORDAN LAND MANAGEMENT AND REGULATORY FRAMEWORK Established in 1927, the Department of Lands and Surveys (DLS) is responsible for all legal property registration in Jordan. The DLS “has been established on a solid basis” according to The Land Tenure Journal, which is a peer-reviewed, open-access journal of the Climate, Energy and Tenure Division of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations [Madanat, 2010]. The Jordan Valley Authority manages various aspects of economic activity and agriculture water management on the Jordan side of the Jordan Valley. The Aqaba Special Economic Zone Authority (ASEZA) is responsible for most government-related issues in the Aqaba Region [Madanat, 2010]. The ASEZA was established in 2001 by the government of Jordan to independently (financially and administratively neutral) manage and regulate the economic development of the Aqaba Special Economic Zone. A description of the ASEZA and the laws and regulations are available at its website (https:// https://aseza.jo/Default/En). The Ministry of Energy and Mineral Resources is the primary regulator of most mining activities in Jordan that provides information (e.g., studies and maps) to interested companies and investors to help facilitate exploration and extraction. These efforts promote a strong regulatory environment with international industry standard environmental and safety best practice regulations [Al Tarawneh, 2016]. 3.2 MINERAL RIGHTS 3.2.1 JORDAN BROMINE COMPANY AND ALBEMARLE JOINT VENTURE JBC was established in 1999 as a joint venture between Albemarle Holdings Company Limited (a wholly owned subsidiary of Albemarle) and APC. Albemarle holds a 50 percent interest in JBC Limited. The bromide-enriched brine is a by-product of potash operations conducted by APC. JBC’s operations primarily consist of the manufacturing of bromine, from which derivative products are made, including

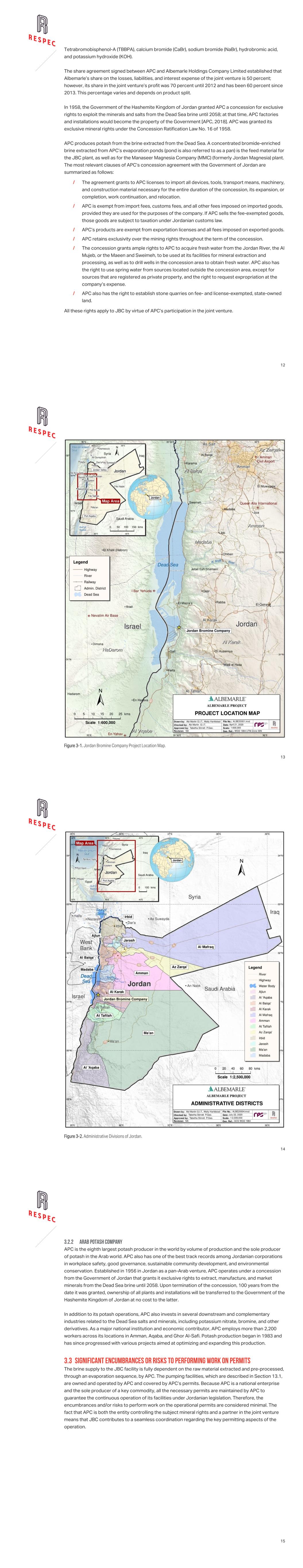

12 Tetrabromobisphenol-A (TBBPA), calcium bromide (CaBr), sodium bromide (NaBr), hydrobromic acid, and potassium hydroxide (KOH). The share agreement signed between APC and Albemarle Holdings Company Limited established that Albemarle’s share on the losses, liabilities, and interest expense of the joint venture is 50 percent; however, its share in the joint venture’s profit was 70 percent until 2012 and has been 60 percent since 2013. This percentage varies and depends on product split. In 1958, the Government of the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan granted APC a concession for exclusive rights to exploit the minerals and salts from the Dead Sea brine until 2058; at that time, APC factories and installations would become the property of the Government [APC, 2018]. APC was granted its exclusive mineral rights under the Concession Ratification Law No. 16 of 1958. APC produces potash from the brine extracted from the Dead Sea. A concentrated bromide-enriched brine extracted from APC’s evaporation ponds (pond is also referred to as a pan) is the feed material for the JBC plant, as well as for the Manaseer Magnesia Company (MMC) (formerly Jordan Magnesia) plant. The most relevant clauses of APC’s concession agreement with the Government of Jordan are summarized as follows: / The agreement grants to APC licenses to import all devices, tools, transport means, machinery, and construction material necessary for the entire duration of the concession, its expansion, or completion, work continuation, and relocation. / APC is exempt from import fees, customs fees, and all other fees imposed on imported goods, provided they are used for the purposes of the company. If APC sells the fee-exempted goods, those goods are subject to taxation under Jordanian customs law. / APC’s products are exempt from exportation licenses and all fees imposed on exported goods. / APC retains exclusivity over the mining rights throughout the term of the concession. / The concession grants ample rights to APC to acquire fresh water from the Jordan River, the Al Mujeb, or the Maeen and Sweimeh, to be used at its facilities for mineral extraction and processing, as well as to drill wells in the concession area to obtain fresh water. APC also has the right to use spring water from sources located outside the concession area, except for sources that are registered as private property, and the right to request expropriation at the company’s expense. / APC also has the right to establish stone quarries on fee- and license-exempted, state-owned land. All these rights apply to JBC by virtue of APC’s participation in the joint venture. 13 Figure 3-1. Jordan Bromine Company Project Location Map. 14 Figure 3-2. Administrative Divisions of Jordan. 15 3.2.2 ARAB POTASH COMPANY APC is the eighth largest potash producer in the world by volume of production and the sole producer of potash in the Arab world. APC also has one of the best track records among Jordanian corporations in workplace safety, good governance, sustainable community development, and environmental conservation. Established in 1956 in Jordan as a pan-Arab venture, APC operates under a concession from the Government of Jordan that grants it exclusive rights to extract, manufacture, and market minerals from the Dead Sea brine until 2058. Upon termination of the concession, 100 years from the date it was granted, ownership of all plants and installations will be transferred to the Government of the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan at no cost to the latter. In addition to its potash operations, APC also invests in several downstream and complementary industries related to the Dead Sea salts and minerals, including potassium nitrate, bromine, and other derivatives. As a major national institution and economic contributor, APC employs more than 2,200 workers across its locations in Amman, Aqaba, and Ghor Al-Safi. Potash production began in 1983 and has since progressed with various projects aimed at optimizing and expanding this production. 3.3 SIGNIFICANT ENCUMBRANCES OR RISKS TO PERFORMING WORK ON PERMITS The brine supply to the JBC facility is fully dependent on the raw material extracted and pre-processed, through an evaporation sequence, by APC. The pumping facilities, which are described in Section 13.1, are owned and operated by APC and covered by APC’s permits. Because APC is a national enterprise and the sole producer of a key commodity, all the necessary permits are maintained by APC to guarantee the continuous operation of its facilities under Jordanian legislation. Therefore, the encumbrances and/or risks to perform work on the operational permits are considered minimal. The fact that APC is both the entity controlling the subject mineral rights and a partner in the joint venture means that JBC contributes to a seamless coordination regarding the key permitting aspects of the operation.

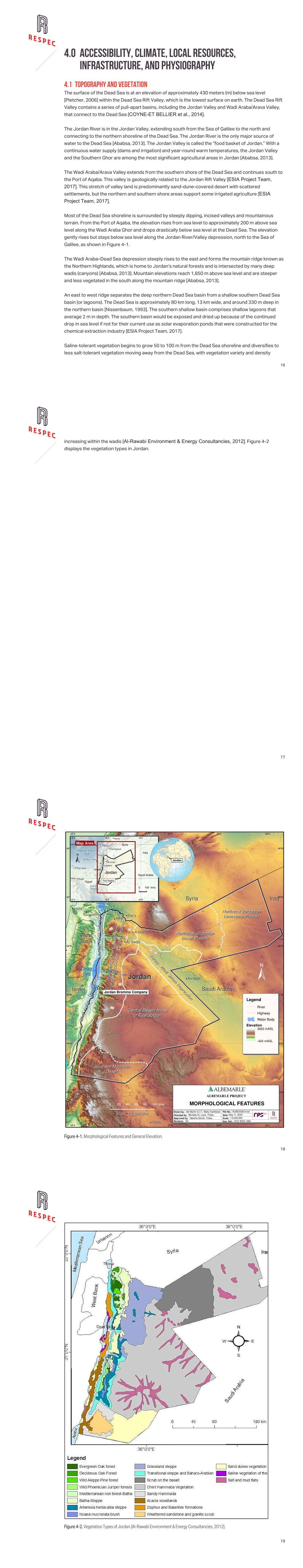

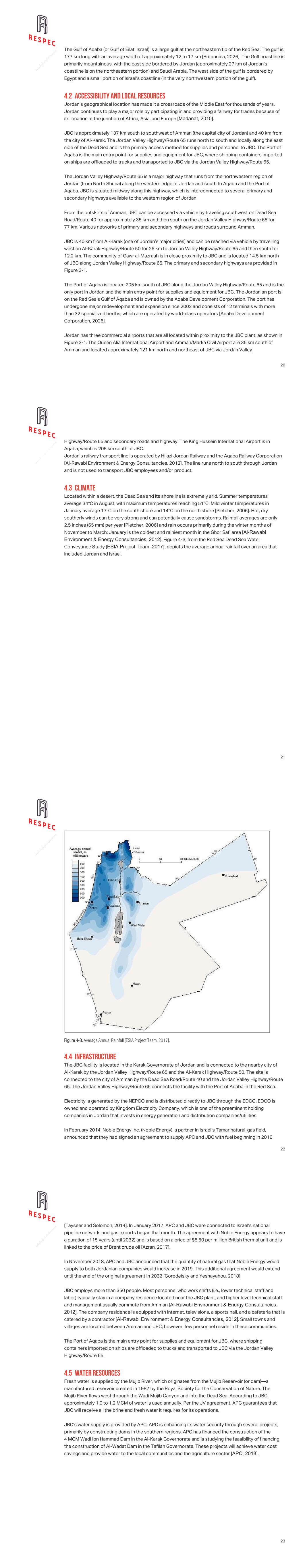

16 4.0 ACCESSIBILITY, CLIMATE, LOCAL RESOURCES, INFRASTRUCTURE, AND PHYSIOGRAPHY 4.1 TOPOGRAPHY AND VEGETATION The surface of the Dead Sea is at an elevation of approximately 430 meters (m) below sea level [Pletcher, 2006] within the Dead Sea Rift Valley, which is the lowest surface on earth. The Dead Sea Rift Valley contains a series of pull-apart basins, including the Jordan Valley and Wadi Araba/Arava Valley, that connect to the Dead Sea [COYNE-ET BELLIER et al., 2014]. The Jordan River is in the Jordan Valley, extending south from the Sea of Galilee to the north and connecting to the northern shoreline of the Dead Sea. The Jordan River is the only major source of water to the Dead Sea [Ababsa, 2013]. The Jordan Valley is called the “food basket of Jordan.” With a continuous water supply (dams and irrigation) and year-round warm temperatures, the Jordan Valley and the Southern Ghor are among the most significant agricultural areas in Jordan [Ababsa, 2013]. The Wadi Araba/Arava Valley extends from the southern shore of the Dead Sea and continues south to the Port of Aqaba. This valley is geologically related to the Jordan Rift Valley [ESIA Project Team, 2017]. This stretch of valley land is predominantly sand-dune-covered desert with scattered settlements, but the northern and southern shore areas support some irrigated agriculture [ESIA Project Team, 2017]. Most of the Dead Sea shoreline is surrounded by steeply dipping, incised valleys and mountainous terrain. From the Port of Aqaba, the elevation rises from sea level to approximately 200 m above sea level along the Wadi Araba Ghor and drops drastically below sea level at the Dead Sea. The elevation gently rises but stays below sea level along the Jordan River/Valley depression, north to the Sea of Galilee, as shown in Figure 4-1. The Wadi Araba–Dead Sea depression steeply rises to the east and forms the mountain ridge known as the Northern Highlands, which is home to Jordan’s natural forests and is intersected by many deep wadis (canyons) [Ababsa, 2013]. Mountain elevations reach 1,850 m above sea level and are steeper and less vegetated in the south along the mountain ridge [Ababsa, 2013]. An east to west ridge separates the deep northern Dead Sea basin from a shallow southern Dead Sea basin (or lagoons). The Dead Sea is approximately 80 km long, 13 km wide, and around 330 m deep in the northern basin [Nissenbaum, 1993]. The southern shallow basin comprises shallow lagoons that average 2 m in depth. The southern basin would be exposed and dried up because of the continued drop in sea level if not for their current use as solar evaporation ponds that were constructed for the chemical extraction industry [ESIA Project Team, 2017]. Saline-tolerant vegetation begins to grow 50 to 100 m from the Dead Sea shoreline and diversifies to less salt-tolerant vegetation moving away from the Dead Sea, with vegetation variety and density 17 increasing within the wadis [Al-Rawabi Environment & Energy Consultancies, 2012]. Figure 4-2 displays the vegetation types in Jordan. 18 Figure 4-1. Morphological Features and General Elevation. 19 Figure 4-2. Vegetation Types of Jordan [Al-Rawabi Environment & Energy Consultancies, 2012].

20 The Gulf of Aqaba (or Gulf of Eilat, Israel) is a large gulf at the northeastern tip of the Red Sea. The gulf is 177 km long with an average width of approximately 12 to 17 km [Britannica, 2026]. The Gulf coastline is primarily mountainous, with the east side bordered by Jordan (approximately 27 km of Jordan’s coastline is on the northeastern portion) and Saudi Arabia. The west side of the gulf is bordered by Egypt and a small portion of Israel’s coastline (in the very northwestern portion of the gulf). 4.2 ACCESSIBILITY AND LOCAL RESOURCES Jordan’s geographical location has made it a crossroads of the Middle East for thousands of years. Jordan continues to play a major role by participating in and providing a fairway for trades because of its location at the junction of Africa, Asia, and Europe [Madanat, 2010]. JBC is approximately 137 km south to southwest of Amman (the capital city of Jordan) and 40 km from the city of Al-Karak. The Jordan Valley Highway/Route 65 runs north to south and locally along the east side of the Dead Sea and is the primary access method for supplies and personnel to JBC. The Port of Aqaba is the main entry point for supplies and equipment for JBC, where shipping containers imported on ships are offloaded to trucks and transported to JBC via the Jordan Valley Highway/Route 65. The Jordan Valley Highway/Route 65 is a major highway that runs from the northwestern region of Jordan (from North Shuna) along the western edge of Jordan and south to Aqaba and the Port of Aqaba. JBC is situated midway along this highway, which is interconnected to several primary and secondary highways available to the western region of Jordan. From the outskirts of Amman, JBC can be accessed via vehicle by traveling southwest on Dead Sea Road/Route 40 for approximately 35 km and then south on the Jordan Valley Highway/Route 65 for 77 km. Various networks of primary and secondary highways and roads surround Amman. JBC is 40 km from Al-Karak (one of Jordan’s major cities) and can be reached via vehicle by travelling west on Al-Karak Highway/Route 50 for 26 km to Jordan Valley Highway/Route 65 and then south for 12.2 km. The community of Gawr al-Mazraah is in close proximity to JBC and is located 14.5 km north of JBC along Jordan Valley Highway/Route 65. The primary and secondary highways are provided in Figure 3-1. The Port of Aqaba is located 205 km south of JBC along the Jordan Valley Highway/Route 65 and is the only port in Jordan and the main entry point for supplies and equipment for JBC. The Jordanian port is on the Red Sea’s Gulf of Aqaba and is owned by the Aqaba Development Corporation. The port has undergone major redevelopment and expansion since 2002 and consists of 12 terminals with more than 32 specialized berths, which are operated by world-class operators [Aqaba Development Corporation, 2026]. Jordan has three commercial airports that are all located within proximity to the JBC plant, as shown in Figure 3-1. The Queen Alia International Airport and Amman/Marka Civil Airport are 35 km south of Amman and located approximately 121 km north and northeast of JBC via Jordan Valley 21 Highway/Route 65 and secondary roads and highway. The King Hussein International Airport is in Aqaba, which is 205 km south of JBC. Jordan’s railway transport line is operated by Hijazi Jordan Railway and the Aqaba Railway Corporation [Al-Rawabi Environment & Energy Consultancies, 2012]. The line runs north to south through Jordan and is not used to transport JBC employees and/or product. 4.3 CLIMATE Located within a desert, the Dead Sea and its shoreline is extremely arid. Summer temperatures average 34°C in August, with maximum temperatures reaching 51°C. Mild winter temperatures in January average 17°C on the south shore and 14°C on the north shore [Pletcher, 2006]. Hot, dry southerly winds can be very strong and can potentially cause sandstorms. Rainfall averages are only 2.5 inches (65 mm) per year [Pletcher, 2006] and rain occurs primarily during the winter months of November to March; January is the coldest and rainiest month in the Ghor Safi area [Al-Rawabi Environment & Energy Consultancies, 2012]. Figure 4-3, from the Red Sea Dead Sea Water Conveyance Study [ESIA Project Team, 2017], depicts the average annual rainfall over an area that included Jordan and Israel. 22 Figure 4-3. Average Annual Rainfall [ESIA Project Team, 2017]. 4.4 INFRASTRUCTURE The JBC facility is located in the Karak Governorate of Jordan and is connected to the nearby city of Al-Karak by the Jordan Valley Highway/Route 65 and the Al-Karak Highway/Route 50. The site is connected to the city of Amman by the Dead Sea Road/Route 40 and the Jordan Valley Highway/Route 65. The Jordan Valley Highway/Route 65 connects the facility with the Port of Aqaba in the Red Sea. Electricity is generated by the NEPCO and is distributed directly to JBC through the EDCO. EDCO is owned and operated by Kingdom Electricity Company, which is one of the preeminent holding companies in Jordan that invests in energy generation and distribution companies/utilities. In February 2014, Noble Energy Inc. (Noble Energy), a partner in Israel’s Tamar natural-gas field, announced that they had signed an agreement to supply APC and JBC with fuel beginning in 2016 23 [Tayseer and Solomon, 2014]. In January 2017, APC and JBC were connected to Israel’s national pipeline network, and gas exports began that month. The agreement with Noble Energy appears to have a duration of 15 years (until 2032) and is based on a price of $5.50 per million British thermal unit and is linked to the price of Brent crude oil [Azran, 2017]. In November 2018, APC and JBC announced that the quantity of natural gas that Noble Energy would supply to both Jordanian companies would increase in 2019. This additional agreement would extend until the end of the original agreement in 2032 [Gorodeisky and Yeshayahou, 2018]. JBC employs more than 350 people. Most personnel who work shifts (i.e., lower technical staff and labor) typically stay in a company residence located near the JBC plant, and higher level technical staff and management usually commute from Amman [Al-Rawabi Environment & Energy Consultancies, 2012]. The company residence is equipped with internet, televisions, a sports hall, and a cafeteria that is catered by a contractor [Al-Rawabi Environment & Energy Consultancies, 2012]. Small towns and villages are located between Amman and JBC; however, few personnel reside in these communities. The Port of Aqaba is the main entry point for supplies and equipment for JBC, where shipping containers imported on ships are offloaded to trucks and transported to JBC via the Jordan Valley Highway/Route 65. 4.5 WATER RESOURCES Fresh water is supplied by the Mujib River, which originates from the Mujib Reservoir (or dam)—a manufactured reservoir created in 1987 by the Royal Society for the Conservation of Nature. The Mujib River flows west through the Wadi Mujib Canyon and into the Dead Sea. According to JBC, approximately 1.0 to 1.2 MCM of water is used annually. Per the JV agreement, APC guarantees that JBC will receive all the brine and fresh water it requires for its operations. JBC’s water supply is provided by APC. APC is enhancing its water security through several projects, primarily by constructing dams in the southern regions. APC has financed the construction of the 4 MCM Wadi Ibn Hammad Dam in the Al-Karak Governorate and is studying the feasibility of financing the construction of Al-Wadat Dam in the Tafilah Governorate. These projects will achieve water cost savings and provide water to the local communities and the agriculture sector [APC, 2018].

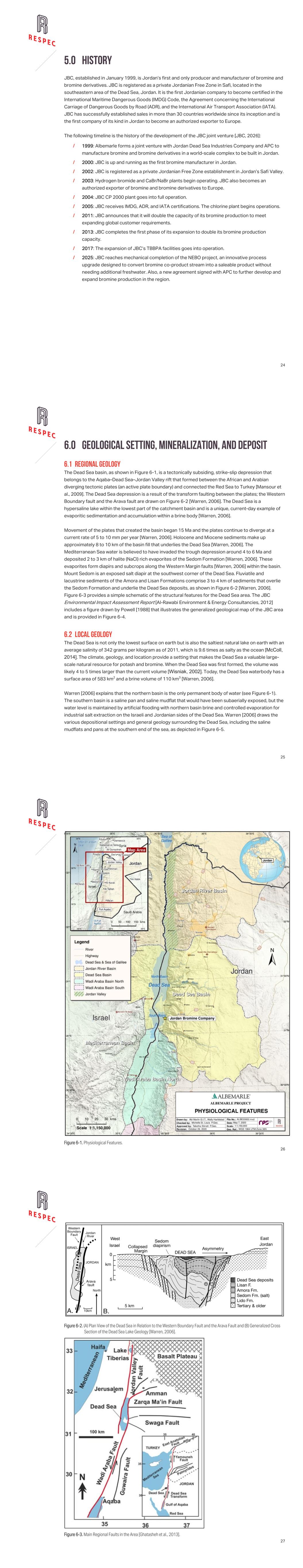

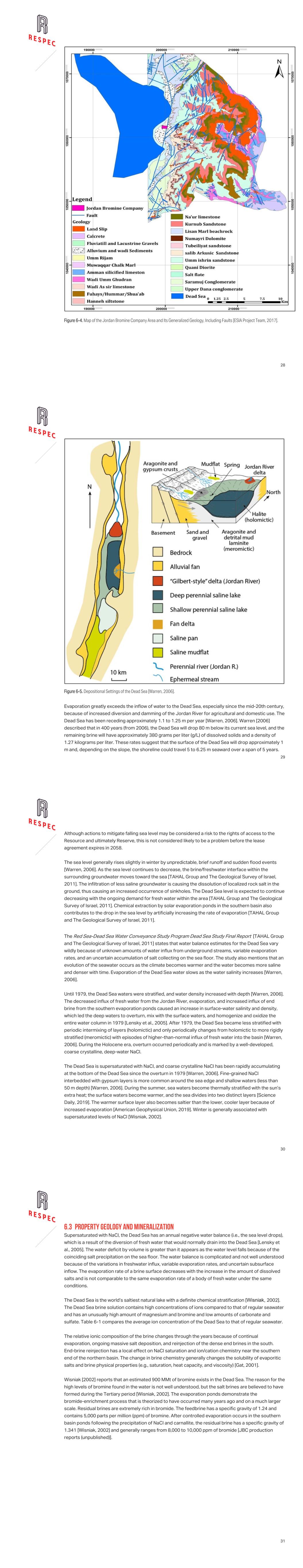

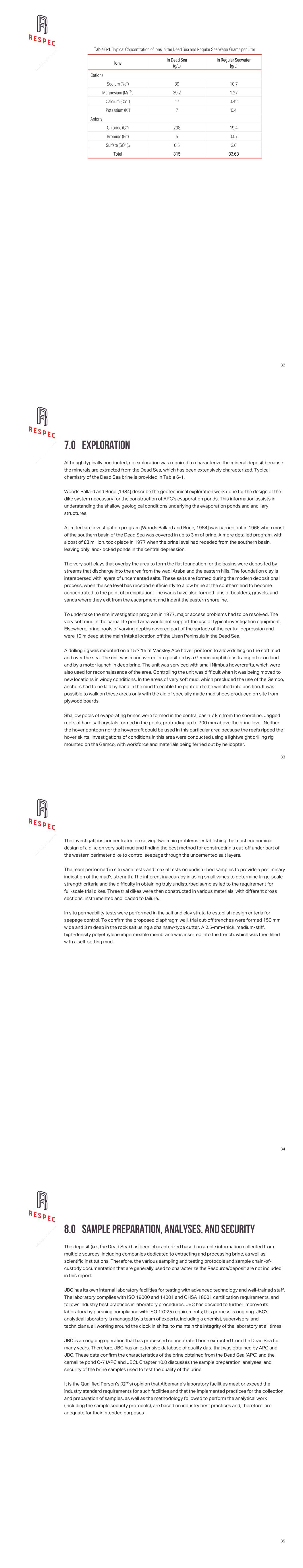

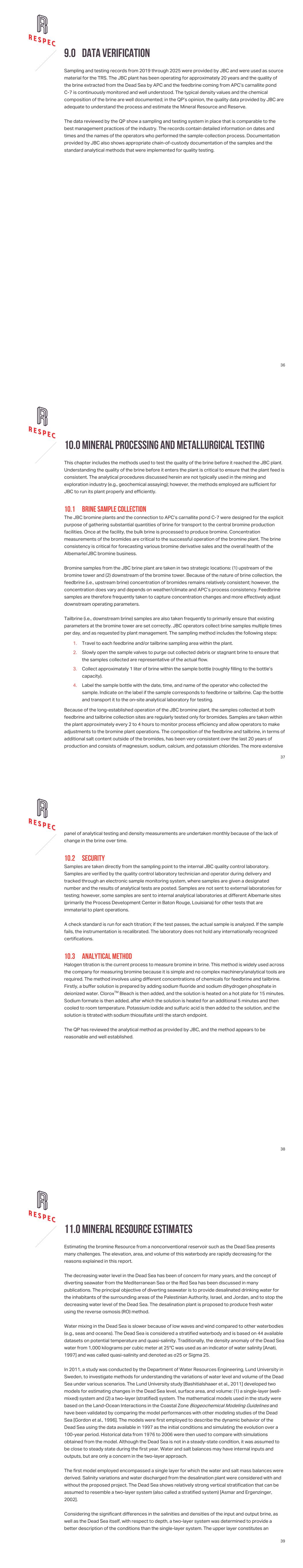

24 5.0 HISTORY JBC, established in January 1999, is Jordan’s first and only producer and manufacturer of bromine and bromine derivatives. JBC is registered as a private Jordanian Free Zone in Safi, located in the southeastern area of the Dead Sea, Jordan. It is the first Jordanian company to become certified in the International Maritime Dangerous Goods (IMDG) Code, the Agreement concerning the International Carriage of Dangerous Goods by Road (ADR), and the International Air Transport Association (IATA). JBC has successfully established sales in more than 30 countries worldwide since its inception and is the first company of its kind in Jordan to become an authorized exporter to Europe. The following timeline is the history of the development of the JBC joint venture [JBC, 2026]: / 1999: Albemarle forms a joint venture with Jordan Dead Sea Industries Company and APC to manufacture bromine and bromine derivatives in a world-scale complex to be built in Jordan. / 2000: JBC is up and running as the first bromine manufacturer in Jordan. / 2002: JBC is registered as a private Jordanian Free Zone establishment in Jordan’s Safi Valley. / 2003: Hydrogen bromide and CaBr/NaBr plants begin operating. JBC also becomes an authorized exporter of bromine and bromine derivatives to Europe. / 2004: JBC CP 2000 plant goes into full operation. / 2005: JBC receives IMDG, ADR, and IATA certifications. The chlorine plant begins operations. / 2011: JBC announces that it will double the capacity of its bromine production to meet expanding global customer requirements. / 2013: JBC completes the first phase of its expansion to double its bromine production capacity. / 2017: The expansion of JBC’s TBBPA facilities goes into operation. / 2025: JBC reaches mechanical completion of the NEBO project, an innovative process upgrade designed to convert bromine co-product stream into a saleable product without needing additional freshwater. Also, a new agreement signed with APC to further develop and expand bromine production in the region. 25 6.0 GEOLOGICAL SETTING, MINERALIZATION, AND DEPOSIT 6.1 REGIONAL GEOLOGY The Dead Sea basin, as shown in Figure 6-1, is a tectonically subsiding, strike-slip depression that belongs to the Aqaba–Dead Sea–Jordan Valley rift that formed between the African and Arabian diverging tectonic plates (an active plate boundary) and connected the Red Sea to Turkey [Mansour et al., 2009]. The Dead Sea depression is a result of the transform faulting between the plates; the Western Boundary fault and the Arava fault are drawn on Figure 6-2 [Warren, 2006]. The Dead Sea is a hypersaline lake within the lowest part of the catchment basin and is a unique, current-day example of evaporitic sedimentation and accumulation within a brine body [Warren, 2006]. Movement of the plates that created the basin began 15 Ma and the plates continue to diverge at a current rate of 5 to 10 mm per year [Warren, 2006]. Holocene and Miocene sediments make up approximately 8 to 10 km of the basin fill that underlies the Dead Sea [Warren, 2006]. The Mediterranean Sea water is believed to have invaded the trough depression around 4 to 6 Ma and deposited 2 to 3 km of halite (NaCl) rich evaporites of the Sedom Formation [Warren, 2006]. These evaporites form diapirs and subcrops along the Western Margin faults [Warren, 2006] within the basin. Mount Sedom is an exposed salt diapir at the southwest corner of the Dead Sea. Fluviatile and lacustrine sediments of the Amora and Lisan Formations comprise 3 to 4 km of sediments that overlie the Sedom Formation and underlie the Dead Sea deposits, as shown in Figure 6-2 [Warren, 2006]. Figure 6-3 provides a simple schematic of the structural features for the Dead Sea area. The JBC Environmental Impact Assessment Report [Al-Rawabi Environment & Energy Consultancies, 2012] includes a figure drawn by Powell [1988] that illustrates the generalized geological map of the JBC area and is provided in Figure 6-4. 6.2 LOCAL GEOLOGY The Dead Sea is not only the lowest surface on earth but is also the saltiest natural lake on earth with an average salinity of 342 grams per kilogram as of 2011, which is 9.6 times as salty as the ocean [McColl, 2014]. The climate, geology, and location provide a setting that makes the Dead Sea a valuable large- scale natural resource for potash and bromine. When the Dead Sea was first formed, the volume was likely 4 to 5 times larger than the current volume [Wisniak, 2002]. Today, the Dead Sea waterbody has a surface area of 583 km2 and a brine volume of 110 km3 [Warren, 2006]. Warren [2006] explains that the northern basin is the only permanent body of water (see Figure 6-1). The southern basin is a saline pan and saline mudflat that would have been subaerially exposed, but the water level is maintained by artificial flooding with northern basin brine and controlled evaporation for industrial salt extraction on the Israeli and Jordanian sides of the Dead Sea. Warren [2006] draws the various depositional settings and general geology surrounding the Dead Sea, including the saline mudflats and pans at the southern end of the sea, as depicted in Figure 6-5. 26 Figure 6-1. Physiological Features. 27 Figure 6-2. (A) Plan View of the Dead Sea in Relation to the Western Boundary Fault and the Arava Fault and (B) Generalized Cross Section of the Dead Sea Lake Geology [Warren, 2006]. Figure 6-3. Main Regional Faults in the Area [Ghatasheh et al., 2013].