SECURITIES & EXCHANGE COMMISSION

WASHINGTON, D.C. 20549

NOTICE OF EXEMPT SOLICITATION (VOLUNTARY SUBMISSION)

NAME OF REGISTRANT: Amazon.com, Inc.

NAME OF PERSON RELYING ON EXEMPTION: SOC Investment Group

ADDRESS OF PERSON RELYING ON EXEMPTION: 1707 L Street, N.W., Suite 350, Washington, D.C. 20036

Written materials are submitted pursuant to Rule 14a-6(g)(1) promulgated under the Securities Exchange Act of 1934:

April 28, 2025

Dear Amazon Shareholder,

We urge you to join us in Voting No on Item 3, the Advisory Vote on Executive Compensation, at this year’s annual meeting. Amazon’s Leadership Development and Compensation Committee (“LDCC”) has not adequately responded to the sizable votes against its pay approach over the past three years – either by altering its approach to pay, or offering an explanation of its determination of the size, timing and appropriateness of the multi-year, time-based, restricted stock grants that comprise virtually all pay for top executives. Beyond these concerns regarding responsiveness, Amazon’s approach to pay fails to align increases in an executive’s “Amazon Wealth” (i.e., the value of their accumulated Amazon shares) with the corresponding returns to shareholders such that executives face no meaningful incentive to allocate capital efficiently. As a result, Amazon’s capital productivity and Economic Value Added/Total Assets (“EVA/TA”) have deteriorated both in absolute terms and compared to the peers Amazon identifies for compensation purposes. Without redirecting the company’s compensation practices, we are concerned that Amazon will continue to drift from its core competencies into an unwieldy and inefficient conglomerate.

Amazon’s Plan Continues to Deviate from Executive Compensation Best Practice

Unlike most other companies, Amazon offers executives neither a short-term nor long-term incentive plan. Instead, Amazon pays modest cash salaries and issues multi-year, time-based restricted stock grants to executives at two-year intervals, other than for the CEO.1 This year, Amazon’s LDCC discusses each grant recipient and their contributions to the company, but without explaining:

| 1) | how these contributions relate to or determine the number of shares granted; |

| 2) | why the LDCC issues overlapping grants (the 2022 grants for these executives ran through 2028, and this year’s grants begin vesting in May 2025)2 ; or |

| 3) | how the number of shares already held by the executive (their pre-grant Amazon Wealth) affects the expected incentive provided by the new grant. |

Similarly, the LDCC has not in the past explained how it determined that the size of new hire or promotional grants, such as those to Mr. Jassy in 2021 or Mr. Selipsky in 2022, or why those grants are appropriate given its understanding of how equity grants affect the incentives executives face.3 In particular, while the company alludes to a peer group that it utilizes for benchmarking purposes, it is unclear how the LDCC benchmarks, or how it considers the value of past grants or the contemporaneous price of Amazon shares in determining how many shares to grant. Finally, Amazon’s grants partially vest with each calendar quarter, effectively guaranteeing the executive substantial regular increases in wealth, but lack both a post-vesting holding period and disclosure of any required level of stock ownership for executives. As a result, executives can cash out their restricted stock grants as they vest, undermining at least one argument Amazon puts forward in defense of these arrangements.

_____________________________

1 Amazon issued new restricted stock grants to Messrs. Olsavsky, Garman, Herrington, Zapolsky, and Selipsky. These grants vest over six years (i.e. through 2031). Each of these executives had previously been granted stock vesting through 2030. Amazon 2025 Proxy Statement on DEF14A, filed on April 10, 2025, pg. 69-70. Amazon has stated that Mr. Jassy’s 2021 promotion grant “was intended to represent most of his compensation in the coming years.” Ibid., pg. 62.

2 See Amazon’s 2023 Proxy Statement on DEF 14A, filed April 13, 2023, pg. 102; Amazon 2025 Proxy Statement on DEF14A, filed on April 10, 2025, pg. 75.

3 Amazon 2022 Proxy Statement on DEF14A, filed April 14, 2022, pg. 98, fn. 7.

Amazon shareholders have opposed the Company’s say on pay proposal at the past three annual meetings, starting in 2022 with 43.9%, 31.5%, and 22.2% of all votes cast, respectively. We note that even the lowest of these totals is well above the average opposition for say on pay for S&P 500 companies in 2024 (10.2%). Moreover, proxy advisor Institutional Shareholder Services (“ISS”) has recommended that clients vote against Amazon’s say on pay resolutions in each of the past three years. ISS recommended “against” say on pay proposals on just 12.7%, 9.6%, and 7.6% of companies respectively from 2022-2024.

Despite engagements with many of its largest shareholders in which Amazon was apparently encouraged to consider utilizing performance metrics in some way, Amazon has not changed its approach.4 Instead, Amazon’s LDCC puts forward a defense of its pay plans citing a 2019 paper by Marc Hodak, as well as a blog post by Norges Bank Investment Management critical of the use of performance shares.5 This research found that companies issuing performance shares had lower performance and larger equity grants than companies relying exclusively on time-based shares. The LDCC further argues that performance criteria can be confusing, complex, and prone to opportunistic manipulation. Finally, as it has in previous proxy statements, the LDCC asserts that had it adopted performance-related goals in 1997 “appropriate to a bookseller, we may have inadvertently discouraged our employees from investing their time and energy in initiatives that later became AWS, Kindle, Alexa, Fulfillment by Amazon, Marketplace, and Prime Video.”6 The LDCC fails to mention the Fire Phone, Amazon Care, Amazon Studios, or Whole Foods, among the initiatives that might have been discouraged.

We find the LDCC’s defense unpersuasive, recalling the adage, “a bad plan is better than no plan at all.” Indeed, we are puzzled that the LDCC seems only to have considered product-market related goals (“appropriate to a bookseller”) rather than performance metrics, such as productivity or EVA/TA, that reflect the efficiency with which management deploys capital. In particular, the LDCC’s defense overlooks Amazon’s increasingly clear mutation into a conglomerate – one that rather unusually combines grocery stores, film and television studios, and data centers (to say nothing of warehousing and delivery). Amazon’s undisciplined capital spending has led to declining relative performance across important measures, including the share price, the one metric the LDCC seems willing to target.

The core of the problem is that the LDCC believes their approach aligns the interests of executives with shareholders. If Amazon executives were required to buy and hold shares in the Company, then it would be the case that only an increase in the share price would generate income for executives (in the form of capital gains). Indeed, this is very much the approach Amazon took to CEO pay during Jeff Bezos’ tenure: Bezos acquired Amazon equity by founding the Company and for most of his tenure retained roughly 20% of shares. Amazon neither issued equity grants to Bezos nor paid him a cash bonus, but because his wealth was so clearly tied to Amazon, his incentives were tied to raising shareholder value in the long term. Indeed, Bezos did not sell Amazon shares in any significant number while CEO. We suspect that the LDCC mistakenly believes that its current approach replicates for current executives the same incentives that Bezos’ substantial Amazon Wealth created.

_____________________________

4 Amazon’s 2025 Proxy Statement filed on DEF14A, filed April 10, 2025, pg. 67.

5 Marc Hodak, “Are Performance Shares Shareholder Friendly?”, Columbia Business School’s Journal of Applied Corporate Finance, (vol 31:3 Summer 2019), cited in Amazon’s 2025 Proxy Statement, pg. 65.

6 Amazon 2025 Proxy Statement, pg. 66.

But as longstanding expert on executive pay Stephen F. O’Byrne has argued, issuing time-based shares to executives in an amount targeted to average peer pay levels without considering past company performance or properly measuring the power of the resulting incentives, can misalign the incentives of executives and shareholders.7 An executive, like Andy Jassy, who is effectively guaranteed substantial future increases in wealth simply does not have an incentive to allocate capital efficiently. Instead, such an executive has an incentive to expend capital not to raise capacity or efficiency in key business activities, but to build up assets such that their scale and complexity make the executive’s continued employment seem necessary, as only this executive actually understands the company. Such conglomerates tend to exhibit lower productivity over time than more focused rivals, and their complexity can make clear comparisons fraught.

In a nutshell, Amazon’s practice of multiple awards over a long period of time guarantees that executives enjoy a substantial increase in their individual Amazon Wealth regardless of the Company’s actual operational or financial performance. Given Amazon’s highly atypical reliance on long-term time-based grants that vest every quarter with low holding requirements, we have opted to measure the value of these grants based on the share price8 on the vesting date for each equity tranche. In practice, it is common for Amazon executives to quickly sell shares following vesting. For instance, from 2017 to early 2025, approximately 3.4 million Amazon shares vested for Mr. Jassy, and he sold just under 2 million of those, or about 58%. Typically, these sales were recorded on the vesting date or the following day.

_____________________________

7 Stephen F. O’Byrne, “Measuring and Improving Pay for Performance,” 39 Handbook of Board Governance, 3rd Edition.

8 Currently, there are several alternative measures in use, each of which has shortcomings. The use of grant-date fair values, while well-intentioned when first introduced, has clearly led to a significant underestimation of the value of equity compensation. On the other hand, measures such as Compensation Actually Paid (“CAP”) may distort the actual gains realized by an executive as the approach effectively assumes that shares are retained and not sold upon vesting.

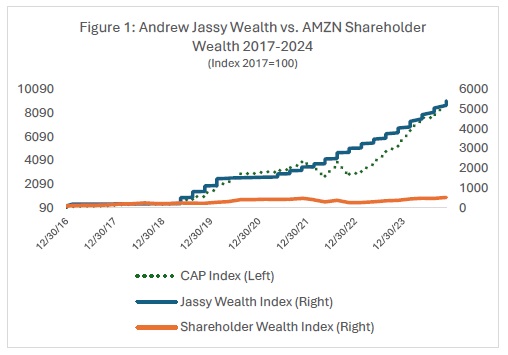

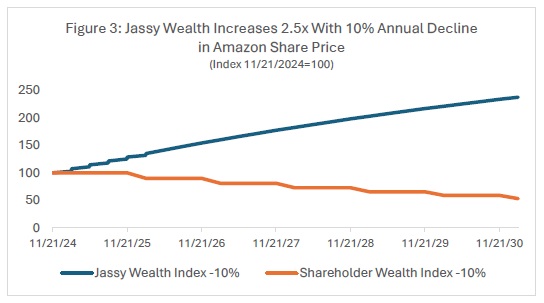

Figure 1 provides a compelling illustration of the mounting gap between Jassy’s Amazon Wealth and the returns enjoyed by shareholders:9

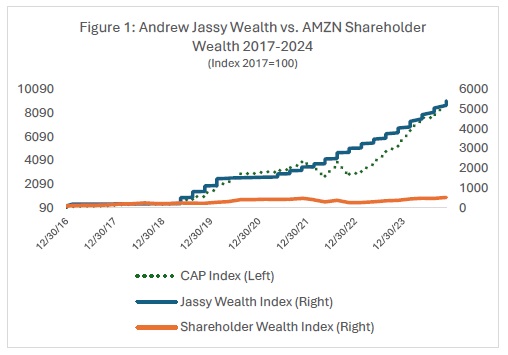

Overall, Jassy increased his Amazon Wealth (with shares valued at the closing price on each vesting date) by approximately 10x the increase in wealth enjoyed by shareholders. We include a calculation of Compensation Actually Paid (CAP), which clearly matches the overall growth in the Jassy Wealth Index, albeit with greater volatility. Going forward, this misalignment is even more severe, as Jassy stands to increase his Amazon Wealth by 270% by 2031 even if Amazon’s share price grows 0% annually.

_____________________________

9 Data for all Figures in this letter were downloaded from Capital IQ.

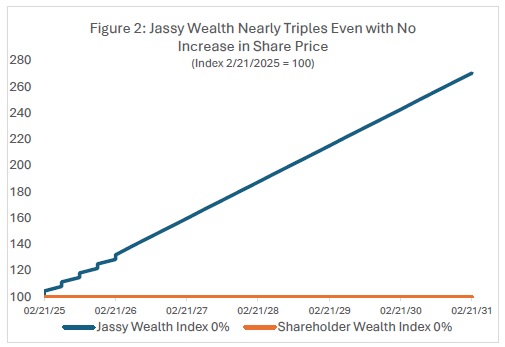

Most damningly for the Compensation Committee’s approach, Jassy’s Amazon Wealth will increase by almost two-and-a-half times even if Amazon’s share price declines by 10% a year.

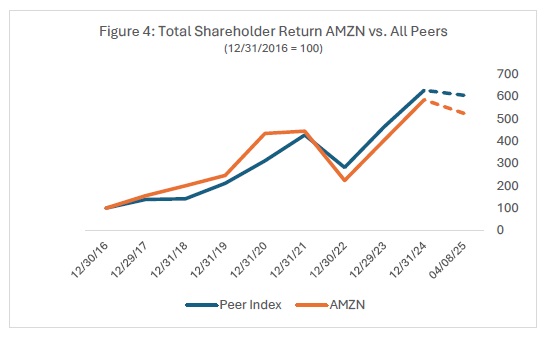

This astonishing degree of misalignment would be troubling even at a company that was performing well and had bright prospects going forward. Unfortunately for Amazon shareholders, that has not been the case. In Figure 4, we present a comparison between Amazon’s total shareholder return since the beginning of 2017 and a market capitalization weighted index of the peers Amazon named on page 72 of its 2025 proxy statement.

While Amazon had been outperforming its peers from 2017 to 2020, starting in early 2021 it began to lag, and by 2025 this underperformance has become substantial, with an index value of 605 for the peer group versus 534 for Amazon.

The Long-Term Threat Posed by Inefficient Capital Allocation

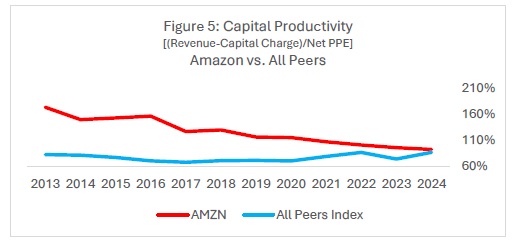

We believe that Amazon’s deteriorating relative share price performance since 2021 has roots in its substantial increases in capital spending over the past decade. While we are ordinarily enthusiastic about companies increasing investment, that enthusiasm is tempered by the necessity that those investments pay off. Amazon’s capital productivity and EVA/TA, however, appear to indicate a significant deterioration in both Amazon’s absolute and relative performance over the past decade. Back in 2013, Amazon’s capital productivity was clearly superior to peers and competitors, even considering the difficulty of identifying exactly which companies count as such. But since then, Amazon’s capital productivity has declined precipitously, nearly converging to the level of its peers. It is important to note that during this time, Amazon often touted its heavy investment spending to expand its logistics operations, to create data centers, and to address mounting evidence of significant safety issues faced by warehouse workers.10

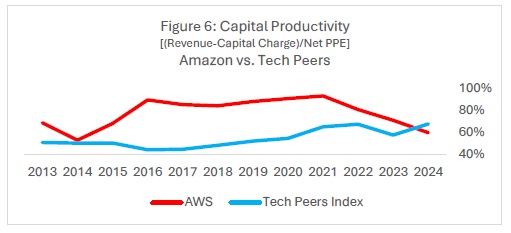

This decline in Amazon’s capital productivity has affected each of its major segments, which is important to consider given the wide variety of business activities under the Amazon umbrella. Figure 6 illustrates the recent decline in capital productivity at Amazon Web Services, compared to its identified peers in the tech industry:

_____________________________

10 See Jeff Bezos’ 2020 letter to shareholders, which states “In 2021, we’ll invest more than $300 million into safety projects, including an initial $66 million to create technology that will help prevent collisions of forklifts and other types of industrial vehicles.” https://www.aboutamazon.com/news/company-news/2020-letter-to-shareholders

As Figure 6 illustrates, Amazon’s investment performance had clearly been superior to the market-capitalization weighted average of its Tech peers from 2015 to 2021, but has declined sharply since then. On average, Amazon’s Tech peers have seen overall growth since 2020 while AWS has experienced a sharp decline.

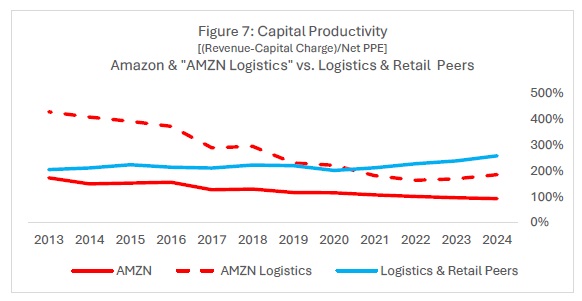

Comparing Amazon’s retail, logistics and warehousing operations (the sum of the Company’s North America and International segments) to retail and logistics peers produces a similar story: a sharp decline from previously superior performance to lagging key peers (in this case the two primary retailers, Wal-Mart and Target).

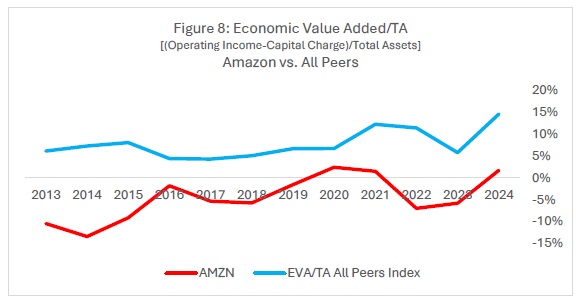

We further consider Amazon’s investment performance based on the ability to generate profits, using EVA/TA. In Figure 8, it is clear that Amazon generally lags peers and has experienced a meaningful relative decline over the past five years.

This steady deterioration of Amazon’s investment performance, coincides with both Amazon’s expansion into multiple industries with at best tangential relationships to online shopping, including film production, brick-and-mortar grocery stores, and branded apparel, and with mounting issues at its warehouses – including industry-leading injury rates, high-turnover, and difficulty recruiting despite well-advertised wage increases.11 We view these developments with trepidation: unless the board is willing to rethink its approach to executive pay and introduce greater discipline in capital allocation and capital spending, Amazon seems set for a period of prolonged underperformance.

_____________________________

11 Strategic Organizing Center, Same Day Injury: Amazon Fails to Deliver Safe Jobs, 2024 https://thesoc.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/342/SOC_Same-Day-Injury-Report-May-2024.pdf; SOC Complaint filed with the SEC July 7, 2022, https://thesoc.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/342/SOC-to-SEC-re-Amazon-complaint-220707_FINAL.pdf; Isobel O’Sullivan, “Amazon’s Staff Turnover Is Costing a Quarter of Its Profits” Tech.co, October 18, 2022. https://tech.co/news/amazon-staff-turnover-costing-quarter-profits

Conclusion

Amazon’s Compensation Committee has selected an approach to paying company executives that fails to deliver on any goals meaningful for shareholders, whether those take the form of superior total shareholder returns or continually improving investment fundamentals. In light of these ongoing concerns, we urge you to Vote No on Item 3 at this year’s annual meeting.

Sincerely,

CorpGov.net

Friends Fiduciary Corporation

Greater Manchester Pension Fund

KPA Tjänstepensionsförsäkring AB

LGPS Central

Mercy Investment Services

Natural Investments

Oxfam America

SHARE

SOC Investment Group

Tulipshare